Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Unclaimed A-bomb victims’ remains, Part 2: Takuo (琢夫) and Takuo (宅雄)

Feb. 5, 2020

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Doubts about remains interred in family grave

Similarly named remains stored in mound

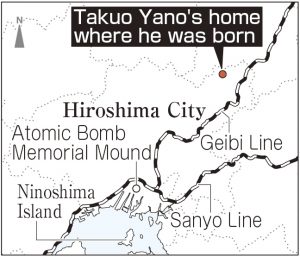

About an hour’s drive northeast of Hiroshima’s downtown is the town of Shiraki, in Asakita Ward. In 1945, Shiraki was then the village of Shiya in the Takata district. Takuo (琢夫in Japanese) Yano was born and raised in the mountainous village. He perished in the atomic bombing when he was 12 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Technical High School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School).

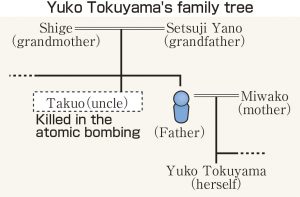

Miwako Yano, 87, wife of Takuo’s older brother, now lives in the home where Takuo was born and raised. “He would have been the same age as I am if he had survived,” Ms. Yano said. She shared with us what she learned about Takuo from Setsuji and Shige Yano, her parents-in-law, while they were alive.

According to their stories, in the spring of 1945, Takuo graduated from the local Shiya National School (now Shiya Elementary School). He was a good student, with many A’s on his report cards. He entered the technical school where his older brother had studied and lived at a relative’s home in Hiroshima. On the morning of August 6, about 190 first-year students had been mobilized to help dismantle buildings for creating firebreaks in the Nakajima-shinmachi district, now part of the city’s Naka Ward.

He suffered burns from the atomic bomb’s thermal waves about 600 meters from the hypocenter. The “Record of the A-bomb Disaster” describes the horrific conditions at that location. “There were countless naked corpses on the ground, making it impossible to identify individual students.”

Father-in-law confesses secret about remains

Setsuji desperately looked for his son in Hiroshima and returned home carrying an urn. He said that Takuo’s school had told him the remains in the urn were his son’s. After some time had passed, however, he made a confession to Miwako. “I received the urn without confirming whose remains were in it,” he said.

The technical school’s alumni association has kept a list of students who died at the time of the atomic bombing. It indicates that Takuo died on the island of Ninoshima on August 12, 1945. During 20 days after August 6, about 10,000 A-bomb victims were said to have been taken to the island. After the war, remains of the victims buried there were unearthed several times and transferred to, and placed in, the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, located in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

A name list of unclaimed remains stored in the mound includes the name “Takuo (宅雄 in Japanese) Yano (of Bokugi, Takata district).” Fifteen years ago, when Yuko Tokuyama, 66, Miwako’s oldest daughter who lives with her mother, visited the Hiroshima Citizens Hospital in Naka Ward for a checkup, she caught glimpse of a hospital wall poster showing a name list of unclaimed A-bomb victims’ remains.

She looked at a name on the list that indicated Takuo Yano but with different kanji characters. She thought it might be that of her uncle, but wondered how that would be possible, given that his remains were already kept in their family grave. Despite different kanji characters, both names are pronounced the same. She was not aware of the place-name Bokugi, but the district written on the list matched the birthplace of her uncle. Doubts began to grow in her mind.

It was around the same time that a man paid Yuko a visit. Kazushige Shimamoto, 81, is a former high school teacher living in Naka Ward. His mother suffered severe burns in the atomic bombing. As he could not leave the issue of the unclaimed remains stored in the Memorial Mound as someone else’s problem, he continued his own investigation designed to identify surviving families of the remains. In the course of that investigation, he found out about Mr. Yano from the Takata district.

Mr. Shimamoto listened to Yuko’s story and went to the Hiroshima City office in charge of such work. He faced a major roadblock, however. In 1979, the city inquired of Setsuji about Takuo (宅雄) Yano’s remains in the mound, obtaining the following response from Setsuji: “I have already received the remains of Takuo (琢夫).”

Two years ago, that reply on a postcard sent from Setsuji was shown to Yuko by staff in the Hiroshima City offices. Based on that information, she was told the city concluded that Takuo Yano, whose remains were in the Memorial Mound, differed from those of her uncle Takuo Yano. “I interpreted that to mean that present circumstances make it difficult to ask for return of his remains,” said Yuko.

Obstacles exist in the way of identification using DNA

Yuko understands all too well the feeling of her grandfather, who tried to convince himself that he had brought back the remains of his own son. Both remains are the same in the sense that their deaths were unreasonable. But she added, “If there is any way to determine the identity of the remains, I want to try.”

A national Japanese government initiative is designed to collect remains of the war dead on Okinawa and at overseas sites related to the war. DNA testing of the remains is conducted when the victim’s family expresses its wishes for such tests. What about the victims of the atomic bombing? “Because many of the remains are burned, an expert told us that DNA analysis would be difficult,” said an official at the Hiroshima City’s Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department. “We haven’t implemented any DNA testing and have no plans for doing so now.”

Even though scientific technology has made great progress, the policy for returning the unclaimed remains to surviving family remains unchanged. It is truly a frustrating situation.

(Originally published on February 5, 2020)

Doubts about remains interred in family grave

Similarly named remains stored in mound

About an hour’s drive northeast of Hiroshima’s downtown is the town of Shiraki, in Asakita Ward. In 1945, Shiraki was then the village of Shiya in the Takata district. Takuo (琢夫in Japanese) Yano was born and raised in the mountainous village. He perished in the atomic bombing when he was 12 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Technical High School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School).

Miwako Yano, 87, wife of Takuo’s older brother, now lives in the home where Takuo was born and raised. “He would have been the same age as I am if he had survived,” Ms. Yano said. She shared with us what she learned about Takuo from Setsuji and Shige Yano, her parents-in-law, while they were alive.

According to their stories, in the spring of 1945, Takuo graduated from the local Shiya National School (now Shiya Elementary School). He was a good student, with many A’s on his report cards. He entered the technical school where his older brother had studied and lived at a relative’s home in Hiroshima. On the morning of August 6, about 190 first-year students had been mobilized to help dismantle buildings for creating firebreaks in the Nakajima-shinmachi district, now part of the city’s Naka Ward.

He suffered burns from the atomic bomb’s thermal waves about 600 meters from the hypocenter. The “Record of the A-bomb Disaster” describes the horrific conditions at that location. “There were countless naked corpses on the ground, making it impossible to identify individual students.”

Father-in-law confesses secret about remains

Setsuji desperately looked for his son in Hiroshima and returned home carrying an urn. He said that Takuo’s school had told him the remains in the urn were his son’s. After some time had passed, however, he made a confession to Miwako. “I received the urn without confirming whose remains were in it,” he said.

The technical school’s alumni association has kept a list of students who died at the time of the atomic bombing. It indicates that Takuo died on the island of Ninoshima on August 12, 1945. During 20 days after August 6, about 10,000 A-bomb victims were said to have been taken to the island. After the war, remains of the victims buried there were unearthed several times and transferred to, and placed in, the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, located in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward.

A name list of unclaimed remains stored in the mound includes the name “Takuo (宅雄 in Japanese) Yano (of Bokugi, Takata district).” Fifteen years ago, when Yuko Tokuyama, 66, Miwako’s oldest daughter who lives with her mother, visited the Hiroshima Citizens Hospital in Naka Ward for a checkup, she caught glimpse of a hospital wall poster showing a name list of unclaimed A-bomb victims’ remains.

She looked at a name on the list that indicated Takuo Yano but with different kanji characters. She thought it might be that of her uncle, but wondered how that would be possible, given that his remains were already kept in their family grave. Despite different kanji characters, both names are pronounced the same. She was not aware of the place-name Bokugi, but the district written on the list matched the birthplace of her uncle. Doubts began to grow in her mind.

It was around the same time that a man paid Yuko a visit. Kazushige Shimamoto, 81, is a former high school teacher living in Naka Ward. His mother suffered severe burns in the atomic bombing. As he could not leave the issue of the unclaimed remains stored in the Memorial Mound as someone else’s problem, he continued his own investigation designed to identify surviving families of the remains. In the course of that investigation, he found out about Mr. Yano from the Takata district.

Mr. Shimamoto listened to Yuko’s story and went to the Hiroshima City office in charge of such work. He faced a major roadblock, however. In 1979, the city inquired of Setsuji about Takuo (宅雄) Yano’s remains in the mound, obtaining the following response from Setsuji: “I have already received the remains of Takuo (琢夫).”

Two years ago, that reply on a postcard sent from Setsuji was shown to Yuko by staff in the Hiroshima City offices. Based on that information, she was told the city concluded that Takuo Yano, whose remains were in the Memorial Mound, differed from those of her uncle Takuo Yano. “I interpreted that to mean that present circumstances make it difficult to ask for return of his remains,” said Yuko.

Obstacles exist in the way of identification using DNA

Yuko understands all too well the feeling of her grandfather, who tried to convince himself that he had brought back the remains of his own son. Both remains are the same in the sense that their deaths were unreasonable. But she added, “If there is any way to determine the identity of the remains, I want to try.”

A national Japanese government initiative is designed to collect remains of the war dead on Okinawa and at overseas sites related to the war. DNA testing of the remains is conducted when the victim’s family expresses its wishes for such tests. What about the victims of the atomic bombing? “Because many of the remains are burned, an expert told us that DNA analysis would be difficult,” said an official at the Hiroshima City’s Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department. “We haven’t implemented any DNA testing and have no plans for doing so now.”

Even though scientific technology has made great progress, the policy for returning the unclaimed remains to surviving family remains unchanged. It is truly a frustrating situation.

(Originally published on February 5, 2020)