Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Unclaimed A-bomb victims’ remains, Part 1: Haru Kajiyama

Feb. 4, 2020

Key to identifying remains was photo registered at the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Challenge is linking National Peace Memorial Hall’s A-bomb victim information with city’s list

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound exists in a corner of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the city’s Naka Ward. The Peace Park was developed during the post-war period after the area was burned to the ground in the summer atomic bombing 75 years ago. The Peace Park’s Memorial Mound contains remains of 70,000 A-bomb victims, with 814 having some kind of information such as a name. The city government of Hiroshima makes and displays posters listing the names of unclaimed remains, but in recent years in particular, the work to identify and return the remains to family has become trying.

On unclaimed remains list, family name “Kajiyama” recorded using incorrect kanji characters with same pronunciation

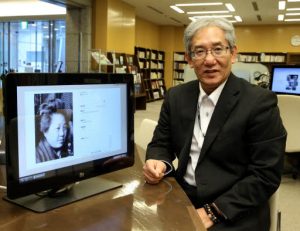

What can be done? On the grounds of Peace Park is also located the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, which has disclosed information on the A-bomb victims to the public, including names and photographs of about 23,000 people registered by family members. With cooperation from the National Peace Memorial Hall, the Chugoku Shimbun matched the victim information stored at the hall with the city’s list of each of the 814 people. A photo of the late Haru Kajiyama (梶山), who at the time lived in Minami-machi 3-chome (now part of Minami Ward), caught the reporter’s attention.

The city’s list includes Haru Kajiyama (鍛治山), who lived in Minami-machi 3-chome. The address and pronunciation of the name are the same between the two information sources.

The Chugoku Shimbun had a chance to meet with Taketo Kajiyama, 83, grandson of Haru and Hiroshima resident. He covered his face with both hands and sobbed. “I’m sure the remains are those of my grandmother,” he said. “I want to place them in our family grave.” He indicated that he had never before seen the city’s list of unclaimed remains.

The Kajiyama family used to make and sell mochi (rice cakes) in a shop in Atago-cho (now part of Higashi Ward). In the spring of 1945, life grew difficult because of the worsening war situation. Koichi Kajiyama, Taketo’s father, went with his family to former Manchuria (now northeastern China) for work. However, Hatsue, Taketo’s sister who was four years older than he and a student at Yamanaka Girls High School attached to Hiroshima Women’s Higher School of Education, desperately begged her father to allow her to stay in Hiroshima to continue her studies. She determined to live in her relative’s home in Minami-machi 3-chome, together with Haru, her grandmother.

When Taketo said good-bye to Hatsue and Haru at Hiroshima Station, Haru gave him a box of rice balls. Hatsue ran on the platform after his now-moving train, seeing him off with hands waving. It turned out to be a moment of final farewell.

In the morning on August 6, Hatsue, a second-year student at school then, was mobilized to dismantle buildings to create fire lanes at Zakoba-cho (now part of Naka Ward), and Haru went to Fujimi-cho (also part of Naka Ward). They never returned. The next June, in 1946, Taketo and his family managed to return to Japan from Manchuria. His mother, Takiko, burst into tears when she was told Haru and Hatsue had died.

Takiko died at age 98 in 2011. While alive, she left writings indicating that Haru, her mother-in-law, was like a real mother to her and that the two women got along and worked so well together that others remarked that her husband, Haru’s son, seemed like a son-in-law. She recalled in her writings Hatsue’s appearance when they parted at Hiroshima Station. “I will never be able to forget her tears. I regret why I didn’t force her to come with us.”

No records available

Gathering information for this article was prompted by the fact that Takiko had registered photos of Haru and Hatsue at the National Peace Memorial Hall. Shuji Kajiyama, 54, Taketo’s oldest son, living in Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima prefecture, looked back on his memories of Takiko, his grandmother. “She was always thinking of them.” In January, this year, Shuji made an inquiry to the city about the remains deemed to be Haru’s, kicking off the investigation and discussions aimed at return of the remains.

Why did it take so long to identify the remains? Until 1986, the city had listed the remains in question under a different name for unknown reasons. When the all remains stored in the Memorial Mound were inspected once again, an envelope with the name “Haru Kajiyama (鍛治山)” was found in an urn. The city then revised the name on its list. In 1996, a local resident at the time made inquiries of the city, asking if the remains might be those of Haru Kajiyama (梶山). But no records remained indicating that the city had tried to directly contact Haru’s family for confirmation.

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound is managed by Hiroshima City, whereas the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims is managed and operated by a city foundation entrusted to do the work by the national government. Would it not be possible to link the data stored at both sites? Can anything be done to have the city’s list of unclaimed remains conveyed more widely to more people?

If names on the list of unclaimed remains can be cross-checked against the variety of A-bomb victim information available, such as photos registered at the National Peace Memorial Hall, the possibility exists that the unclaimed remains can be linked with family members. However, such efforts may not quickly deliver results. Hatsue’s remains have still not been found.

(Originally published on February 4, 2020)