Letters and diaries of Tomoko Nakabayashi, A-bomb survivor who died during medical treatment in the U.S. in 1956, are discovered

Aug. 2, 2019

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

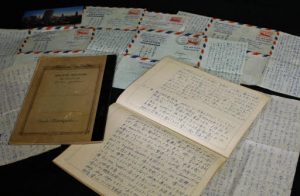

It has been learned that letters and diaries written by Tomoko Nakabayashi, one of the 25 single women from Hiroshima who traveled to the United States in 1955 to undergo medical treatment, have been kept by her sisters. Ms. Nakabayashi died in 1956 at the age of 27 while she was in the United States. In her letters and diaries, she detailed her feelings of hope and anxiety with regard to her plastic surgeries there as well as her interactions with the local people. It also turned out that her name was not listed in the register of the A-bomb victims. The City of Hiroshima will add her name to the register, which will be placed into the stone chest within the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park during the Peace Memorial Ceremony, to be held on August 6.

Eiko Shinohara, 91, Tomoko’s older sister who lives in Mitaka, Tokyo, has six letters from her, and Shigeko Inoue, 83, her younger sister who lives in Suginami Ward, Tokyo, has two diaries, which used to be kept by their late mother. They decided to make these items available to the public in the hope that people could learn more about her. At the same time, they applied to the City of Hiroshima to have Tomoko’s name added to the register of A-bomb victims. Both sisters also experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, evacuating there from Tokyo after the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 10, 1945.

On August 6, 1945, Tomoko went to work at the Hiroshima prefectural industrial research institute in Higashi-Hakushima-cho, where she was exposed to the atomic bomb about 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. The family lived in Hakushima-Kita-machi at that time. “Her clothes were still on fire when she got back home,” Shigeko said.

Although Tomoko became a teacher at a dressmaking school, she was unable to move her right elbow and left fingers freely. Eiko was with Tomoko when they heard the news on the radio in April 1955 announcing the names of the women who were given the opportunity to receive medical treatment in the United States. Eiko said, “We were so happy when Tomoko’s name was called.” At the time, no assistance was being provided to the A-bomb survivors.

The effort to bring A-bombed women to the United States for medical treatment was led by Norman Cousins, an American journalist who also initiated support in the United States for “atomic bomb orphans.” Mr. Cousins, who died in 1990, worked with the City of Hiroshima to carry out these projects. Mount Sinai Hospital, one of the best hospitals in New York, and anti-war Quakers lent their support and this effort to provide medical treatment to A-bombed women lasted for a year and a half.

Tomoko began her diary on May 10, 1955, the day after she arrived in New York, and ended on July 12. The first part of the diary offers a detailed description of the daily life of the Quaker family she stayed with. The women from Hiroshima stayed with these families in pairs and moved to a different family about every month. She also jotted down practical English expressions that she had newly learned, like “If you please.”

“I was discharged from the hospital after being there more than a month.” The first operation was performed on August 16 of the same year, grafting skin from her left thigh onto her right arm including the back of her hand. In a long letter sent to Eiko, who was a year older and had returned to Tokyo to get married, Tomoko wrote about many things: her progress after her operation; the encouraging words she received from Hatsuko Yokoyama, a second-generation Japanese-American who escorted the 25 women from Hiroshima and served as their translator (Ms. Yokoyama died in 1999); and her plans for the future after returning to Japan.

“I will speak to the teacher about studying in the United States.” In her last letter, mailed on April 30, 1956, she talked about her plan to study at a dressmaking school in the United States to improve her skills. She underwent a third operation on May 24 (May 25 in Japan), but never awoke from the anesthesia. According to the results of the autopsy, she died of “heart failure.”

These are valuable materials which detail not only the medical treatment that A-bomb survivors received, but also how the people overseas viewed the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. At that time, these 25 single women, dubbed the “Hiroshima Girls,” helped stir public opinion for relief measures for A-bomb survivors through the media coverage they generated, which led to the enactment of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law in 1957. These women also made the American people aware of the victims of the atomic bombings. The damage done to human beings by the atomic bombs should be talked about concretely, with proper names, not in an abstract way. I hope that the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum will make more effort to collect and display historical materials like these.

(Originally published on August 2, 2019)

It has been learned that letters and diaries written by Tomoko Nakabayashi, one of the 25 single women from Hiroshima who traveled to the United States in 1955 to undergo medical treatment, have been kept by her sisters. Ms. Nakabayashi died in 1956 at the age of 27 while she was in the United States. In her letters and diaries, she detailed her feelings of hope and anxiety with regard to her plastic surgeries there as well as her interactions with the local people. It also turned out that her name was not listed in the register of the A-bomb victims. The City of Hiroshima will add her name to the register, which will be placed into the stone chest within the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park during the Peace Memorial Ceremony, to be held on August 6.

Eiko Shinohara, 91, Tomoko’s older sister who lives in Mitaka, Tokyo, has six letters from her, and Shigeko Inoue, 83, her younger sister who lives in Suginami Ward, Tokyo, has two diaries, which used to be kept by their late mother. They decided to make these items available to the public in the hope that people could learn more about her. At the same time, they applied to the City of Hiroshima to have Tomoko’s name added to the register of A-bomb victims. Both sisters also experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, evacuating there from Tokyo after the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 10, 1945.

On August 6, 1945, Tomoko went to work at the Hiroshima prefectural industrial research institute in Higashi-Hakushima-cho, where she was exposed to the atomic bomb about 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. The family lived in Hakushima-Kita-machi at that time. “Her clothes were still on fire when she got back home,” Shigeko said.

Although Tomoko became a teacher at a dressmaking school, she was unable to move her right elbow and left fingers freely. Eiko was with Tomoko when they heard the news on the radio in April 1955 announcing the names of the women who were given the opportunity to receive medical treatment in the United States. Eiko said, “We were so happy when Tomoko’s name was called.” At the time, no assistance was being provided to the A-bomb survivors.

The effort to bring A-bombed women to the United States for medical treatment was led by Norman Cousins, an American journalist who also initiated support in the United States for “atomic bomb orphans.” Mr. Cousins, who died in 1990, worked with the City of Hiroshima to carry out these projects. Mount Sinai Hospital, one of the best hospitals in New York, and anti-war Quakers lent their support and this effort to provide medical treatment to A-bombed women lasted for a year and a half.

Tomoko began her diary on May 10, 1955, the day after she arrived in New York, and ended on July 12. The first part of the diary offers a detailed description of the daily life of the Quaker family she stayed with. The women from Hiroshima stayed with these families in pairs and moved to a different family about every month. She also jotted down practical English expressions that she had newly learned, like “If you please.”

“I was discharged from the hospital after being there more than a month.” The first operation was performed on August 16 of the same year, grafting skin from her left thigh onto her right arm including the back of her hand. In a long letter sent to Eiko, who was a year older and had returned to Tokyo to get married, Tomoko wrote about many things: her progress after her operation; the encouraging words she received from Hatsuko Yokoyama, a second-generation Japanese-American who escorted the 25 women from Hiroshima and served as their translator (Ms. Yokoyama died in 1999); and her plans for the future after returning to Japan.

“I will speak to the teacher about studying in the United States.” In her last letter, mailed on April 30, 1956, she talked about her plan to study at a dressmaking school in the United States to improve her skills. She underwent a third operation on May 24 (May 25 in Japan), but never awoke from the anesthesia. According to the results of the autopsy, she died of “heart failure.”

Comment by Satoru Ubuki, 72, an expert on the history of the A-bombing and a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University

These are valuable materials which detail not only the medical treatment that A-bomb survivors received, but also how the people overseas viewed the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. At that time, these 25 single women, dubbed the “Hiroshima Girls,” helped stir public opinion for relief measures for A-bomb survivors through the media coverage they generated, which led to the enactment of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law in 1957. These women also made the American people aware of the victims of the atomic bombings. The damage done to human beings by the atomic bombs should be talked about concretely, with proper names, not in an abstract way. I hope that the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum will make more effort to collect and display historical materials like these.

(Originally published on August 2, 2019)