From the Editorial Room: Messages left by foreign visitors to Hiroshima museum express common wish for peace

Aug. 2, 2019

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

A company employee who is 36 and a resident of Minami Ward, Hiroshima sent a letter to the editorial room of the Chugoku Shimbun, writing, “When I visited the Peace Memorial Museum and looked at the notebooks that contain impressions from museum visitors, I found many messages that are written in foreign languages other than English. I’d like to know what those messages say.”

The notebooks this person refers to are set out for visitors to share their impressions after touring the museum. Of the messages written in foreign languages in these notebooks, there were five languages that the museum curators couldn’t understand. We had them translated into Japanese with the help of international residents living in Japan.

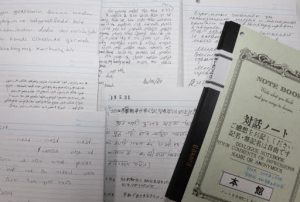

In writing this article, I visited the museum in late July and looked at a total of 13 notebooks. The messages written in them are from April 25, the day that the museum’s main building was reopened after renovations, to July 3. Nearly every page of these notebooks includes messages that were written in languages other than English and Japanese.

For the messages written in Hebrew, the official language of Israel, a request for translation help was made to Dany Nehushtai, 62, a furniture artist who lives in Saitama Prefecture. According to Mr. Nehushtai, visitors from Israel link the atomic bombing to the Holocaust, when the Jewish people were systematically massacred by Nazi Germany. The translation reads, “I can empathize with the tragedy in Hiroshima, as a person belonging to an ethnic group that experienced a great tragedy” and “I can empathize with the tragedy in Hiroshima very much, because of the fact that whole families of Jews were also killed, including mine.”

City’s reconstruction is praised

Cao Hong Ngoc, 35, a member of the Hiroshima Vietnam Association, a non-profit organization (NPO) in Nishi Ward, was asked to translate the Vietnamese messages. One of the Vietnamese visitors recalled the Vietnam War and wrote that their country experienced the same kind suffering as Japan. There was also a message that praised Japan’s post-war reconstruction efforts by saying, “Japan is very resilient.”

One visitor from Saudi Arabia wrote in Arabic, “There is no room to legitimatize what happened in Hiroshima. The museum shows very well how to produce nuclear weapons. It calls for reduction and non-use of these weapons.” Aoe Tanami, 48, an associate professor at Hiroshima City University who translated the Arabic message, referred to the damage caused by depleted uranium ammunition in Iraq, and shared her assumptions by saying, “There is rising nuclear pollution in Arabic-speaking areas, too. Israel is a de facto nuclear weapon state so people in the region seem to be very sensitive about the issue of nuclear weapons.”

Messages calling for peace were universal in the notebooks. Stephanie Eto, 23, a company employee living in Isezaki, Gunma Prefecture, translated a message from Portuguese into Japanese, which appeals for an end to war. Daiki Tamura, 23, a university student living in Katsushika, Tokyo, translated a Spanish message into Japanese, a plea to God to give wisdom and love to human beings in order to preserve peace in the world. Such impressions have reaffirmed for me that people will naturally respond in this way once they have understood the inhumanity of nuclear weapons first-hand through their visit to the museum.

Museum staff would like to make use of messages

Two notebooks for visitors’ impressions are set out on the first floor of the museum’s east building and in the gallery of the main building, respectively. Such notebooks have been used since 1970, 15 years after the museum first opened. To date (as of August 1), a total of 1,548 notebooks have been filled with messages. These messages are read by the museum curators and then kept at the museum permanently. However, messages written in foreign languages are translated into Japanese only when they are written in English, Korean, French, or Russian. Shuichi Kato, the manager of the museum’s curatorial division, said, “As some of the staff also wanted to know the international visitors’ impressions of the museum, they have asked their acquaintances to translate the messages in Spanish or Hebrew pro bono. It would be difficult to translate messages made in every foreign language into Japanese because it takes so much time and money. But we would like to continue making use of these notebooks as one of the ways to understand what visitors think after touring the museum.”

While leafing through the notebooks, I saw a long message written in Bengali as well as many messages where the languages used could not be determined. With the number of international visitors to the museum continuing to grow, would it be worthwhile addressing this situation so that their messages can be used more effectively?

(Originally published on August 2, 2019)

A company employee who is 36 and a resident of Minami Ward, Hiroshima sent a letter to the editorial room of the Chugoku Shimbun, writing, “When I visited the Peace Memorial Museum and looked at the notebooks that contain impressions from museum visitors, I found many messages that are written in foreign languages other than English. I’d like to know what those messages say.”

The notebooks this person refers to are set out for visitors to share their impressions after touring the museum. Of the messages written in foreign languages in these notebooks, there were five languages that the museum curators couldn’t understand. We had them translated into Japanese with the help of international residents living in Japan.

In writing this article, I visited the museum in late July and looked at a total of 13 notebooks. The messages written in them are from April 25, the day that the museum’s main building was reopened after renovations, to July 3. Nearly every page of these notebooks includes messages that were written in languages other than English and Japanese.

For the messages written in Hebrew, the official language of Israel, a request for translation help was made to Dany Nehushtai, 62, a furniture artist who lives in Saitama Prefecture. According to Mr. Nehushtai, visitors from Israel link the atomic bombing to the Holocaust, when the Jewish people were systematically massacred by Nazi Germany. The translation reads, “I can empathize with the tragedy in Hiroshima, as a person belonging to an ethnic group that experienced a great tragedy” and “I can empathize with the tragedy in Hiroshima very much, because of the fact that whole families of Jews were also killed, including mine.”

City’s reconstruction is praised

Cao Hong Ngoc, 35, a member of the Hiroshima Vietnam Association, a non-profit organization (NPO) in Nishi Ward, was asked to translate the Vietnamese messages. One of the Vietnamese visitors recalled the Vietnam War and wrote that their country experienced the same kind suffering as Japan. There was also a message that praised Japan’s post-war reconstruction efforts by saying, “Japan is very resilient.”

One visitor from Saudi Arabia wrote in Arabic, “There is no room to legitimatize what happened in Hiroshima. The museum shows very well how to produce nuclear weapons. It calls for reduction and non-use of these weapons.” Aoe Tanami, 48, an associate professor at Hiroshima City University who translated the Arabic message, referred to the damage caused by depleted uranium ammunition in Iraq, and shared her assumptions by saying, “There is rising nuclear pollution in Arabic-speaking areas, too. Israel is a de facto nuclear weapon state so people in the region seem to be very sensitive about the issue of nuclear weapons.”

Messages calling for peace were universal in the notebooks. Stephanie Eto, 23, a company employee living in Isezaki, Gunma Prefecture, translated a message from Portuguese into Japanese, which appeals for an end to war. Daiki Tamura, 23, a university student living in Katsushika, Tokyo, translated a Spanish message into Japanese, a plea to God to give wisdom and love to human beings in order to preserve peace in the world. Such impressions have reaffirmed for me that people will naturally respond in this way once they have understood the inhumanity of nuclear weapons first-hand through their visit to the museum.

Museum staff would like to make use of messages

Two notebooks for visitors’ impressions are set out on the first floor of the museum’s east building and in the gallery of the main building, respectively. Such notebooks have been used since 1970, 15 years after the museum first opened. To date (as of August 1), a total of 1,548 notebooks have been filled with messages. These messages are read by the museum curators and then kept at the museum permanently. However, messages written in foreign languages are translated into Japanese only when they are written in English, Korean, French, or Russian. Shuichi Kato, the manager of the museum’s curatorial division, said, “As some of the staff also wanted to know the international visitors’ impressions of the museum, they have asked their acquaintances to translate the messages in Spanish or Hebrew pro bono. It would be difficult to translate messages made in every foreign language into Japanese because it takes so much time and money. But we would like to continue making use of these notebooks as one of the ways to understand what visitors think after touring the museum.”

While leafing through the notebooks, I saw a long message written in Bengali as well as many messages where the languages used could not be determined. With the number of international visitors to the museum continuing to grow, would it be worthwhile addressing this situation so that their messages can be used more effectively?

(Originally published on August 2, 2019)