Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Unclaimed A-bomb victims’ remains, Part 7: Jizo, guardian deity of children

Feb. 12, 2020

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Most of the approximately 70,000 remains stored in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward) have not been identified and are stored in the form of large amounts of bone fragments. Many temples in the city of Hiroshima also have unclaimed or unidentified remains. Some temples have remains equivalent to the contents of five large boxes, and others have remains that are only powder. In this way, nameless remains of A-bomb victims lie at rest in the busy, bustling center of the city, an area typically filled with shoppers and tourists.

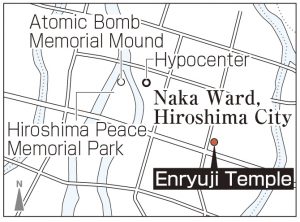

Enryuji Temple, commonly known as Tokasan, is located in Mikawa-cho, Naka Ward. There, a statue of Jizo (guardian deity of children) stands quietly in the graveyard behind the temple’s main hall. To the east of the temple is Nagarekawa, the biggest entertainment district in the prefecture of Hiroshima. In 1945, there was also a small branch school of Takeya National School (now Takeya Elementary School) and Fukuromachi National School (now Fukuromachi Elementary School) in Enryuji Temple, with an enrollment of about 20 first- and second-grade elementary school students. Because the temple was located roughly one kilometer from the hypocenter, many children lost their lives in the raging fires caused by the atomic bombing.

Yoshiko Matsuoka, 87, the oldest daughter of the chief priest of the temple at that time, lives now in the city of Akaiwa, Okayama Prefecture. “Human bones just like small, broken fragments remained here and there on the grounds surrounding the main hall. I had no idea who they belonged to,” she explained. “When I pinched them with my fingers, I could see that they were as fragile as ash.” She said she carefully put them on roof tiles and buried them in a corner of the temple grounds, placing a stone in the spot to mark the location of the remains.

At the time of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Ms. Matsuoka was 12 years old and a first-year student at Hijiyama Girls’ High School (now Hijiyama Girls’ Junior and Senior High School). Not in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, she survived the atomic bombing. When she returned two days after the bombing, she noticed the temple grounds had been completely transformed. “I assumed that because the children’s parents had also probably died in the atomic bombing, no one was able to search for the children’s remains.” Ms. Matsuoka thus erected a wooden monument on the scorched site and later placed a Jizo statue there.

Takeshi Ochi (died in 1998 at 59), who at the time was a first-year student at Fukuromachi National School, had told his wife Asako, 77, who now lives in the town of Kumano-cho, Hiroshima prefecture, “Only three people who went out of the main hall to get some drinking water survived.” Mr. Ochi visited Enryuji Temple every summer around the Bon period with Asako to mourn those who had died there. “They were classmates I studied with.”

Eiko Otsuka, 84, a resident of Asakita Ward, lost her younger brother, Yoshitaka Kuze, a second-year student at what was then Takeya National School, in the atomic bombing. She learned of the existence of the Jizo statue for the first time from this interview with the Chugoku Shimbun. In the interview, thinking that her immediate family’s remains might also be at rest with those of other atomic bombing victims at Enryuji Temple, she shed tears.

One morning in the spring of 1945, Ms. Otsuka was about to leave her home for the town of Kake-cho (now part of Akiota-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture) as part of an evacuation of schoolchildren. While she was dozing in bed, Yoshitaka, who loved his older sister, got into her futon and kissed her all over her face. “I still cannot forget the touch of Yoshitaka’s soft, warm lips,” said Ms. Otsuka.

Even after August 6, Ms. Otsuka’s parents did not come to see her at the site where she had been evacuated in Kake-cho. In autumn, her relatives came to get her. At her grandfather’s house in Kyoto, she saw her parent’s remains but Yoshitaka’s remains were not there.

She knows in her imagination that Yoshitaka could have died at Enryuji Temple. She also knows that if she were to go there, it would be too painful for her. She has never been to the temple grounds or to the Tokasan Festival in early summer. Believing that her brother has been kept in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, Ms. Otsuka has visited the memorial mound on the date of the Hiroshima atomic bombing and conveys to him a message. “It’s nice that so many people visit you and give you flowers.”

Responding to our invitation to visit together the statue of Jizo, the guardian deity of children, she paused and said quietly, “I cannot go because it would still be too painful.”

The information we have gathered shows that unidentified A-bomb victims’ remains not returned to family are kept at 11 temples in the prefectures of Hiroshima and Yamaguchi, including Chokakuji Temple, in Asakita Ward, Hiroshima, which contains the remains of an estimated 10-plus people. We believe that to remember the existence of A-bomb victims’ remains represents our vow to pass on stories about the catastrophic disaster caused by the atomic bombings to future generations.

At the end of last year, Nobuko Nakatani, 65, wife of Enryuji Temple’s chief priest, and her oldest son Koin, 36, vice-chief priest, installed a panel next to the Jizo statue that explains about the child victims of the atomic bombing. They hope many visitors to the temple will join hands in front of the Jizo statue to pray for the repose of the souls of deceased children. “We will continue to take good care of their remains.”

(Originally published on February 12, 2020)

Memorial service for A-bomb child victims’ small fragmented remains

Children died on temple’s grounds

Most of the approximately 70,000 remains stored in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward) have not been identified and are stored in the form of large amounts of bone fragments. Many temples in the city of Hiroshima also have unclaimed or unidentified remains. Some temples have remains equivalent to the contents of five large boxes, and others have remains that are only powder. In this way, nameless remains of A-bomb victims lie at rest in the busy, bustling center of the city, an area typically filled with shoppers and tourists.

Branch school with enrollment of 20 students

Enryuji Temple, commonly known as Tokasan, is located in Mikawa-cho, Naka Ward. There, a statue of Jizo (guardian deity of children) stands quietly in the graveyard behind the temple’s main hall. To the east of the temple is Nagarekawa, the biggest entertainment district in the prefecture of Hiroshima. In 1945, there was also a small branch school of Takeya National School (now Takeya Elementary School) and Fukuromachi National School (now Fukuromachi Elementary School) in Enryuji Temple, with an enrollment of about 20 first- and second-grade elementary school students. Because the temple was located roughly one kilometer from the hypocenter, many children lost their lives in the raging fires caused by the atomic bombing.

Yoshiko Matsuoka, 87, the oldest daughter of the chief priest of the temple at that time, lives now in the city of Akaiwa, Okayama Prefecture. “Human bones just like small, broken fragments remained here and there on the grounds surrounding the main hall. I had no idea who they belonged to,” she explained. “When I pinched them with my fingers, I could see that they were as fragile as ash.” She said she carefully put them on roof tiles and buried them in a corner of the temple grounds, placing a stone in the spot to mark the location of the remains.

At the time of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Ms. Matsuoka was 12 years old and a first-year student at Hijiyama Girls’ High School (now Hijiyama Girls’ Junior and Senior High School). Not in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, she survived the atomic bombing. When she returned two days after the bombing, she noticed the temple grounds had been completely transformed. “I assumed that because the children’s parents had also probably died in the atomic bombing, no one was able to search for the children’s remains.” Ms. Matsuoka thus erected a wooden monument on the scorched site and later placed a Jizo statue there.

Takeshi Ochi (died in 1998 at 59), who at the time was a first-year student at Fukuromachi National School, had told his wife Asako, 77, who now lives in the town of Kumano-cho, Hiroshima prefecture, “Only three people who went out of the main hall to get some drinking water survived.” Mr. Ochi visited Enryuji Temple every summer around the Bon period with Asako to mourn those who had died there. “They were classmates I studied with.”

Eiko Otsuka, 84, a resident of Asakita Ward, lost her younger brother, Yoshitaka Kuze, a second-year student at what was then Takeya National School, in the atomic bombing. She learned of the existence of the Jizo statue for the first time from this interview with the Chugoku Shimbun. In the interview, thinking that her immediate family’s remains might also be at rest with those of other atomic bombing victims at Enryuji Temple, she shed tears.

One morning in the spring of 1945, Ms. Otsuka was about to leave her home for the town of Kake-cho (now part of Akiota-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture) as part of an evacuation of schoolchildren. While she was dozing in bed, Yoshitaka, who loved his older sister, got into her futon and kissed her all over her face. “I still cannot forget the touch of Yoshitaka’s soft, warm lips,” said Ms. Otsuka.

Even after August 6, Ms. Otsuka’s parents did not come to see her at the site where she had been evacuated in Kake-cho. In autumn, her relatives came to get her. At her grandfather’s house in Kyoto, she saw her parent’s remains but Yoshitaka’s remains were not there.

She knows in her imagination that Yoshitaka could have died at Enryuji Temple. She also knows that if she were to go there, it would be too painful for her. She has never been to the temple grounds or to the Tokasan Festival in early summer. Believing that her brother has been kept in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, Ms. Otsuka has visited the memorial mound on the date of the Hiroshima atomic bombing and conveys to him a message. “It’s nice that so many people visit you and give you flowers.”

Responding to our invitation to visit together the statue of Jizo, the guardian deity of children, she paused and said quietly, “I cannot go because it would still be too painful.”

Remains of A-bomb victims are kept at 11 temples in two different prefectures

The information we have gathered shows that unidentified A-bomb victims’ remains not returned to family are kept at 11 temples in the prefectures of Hiroshima and Yamaguchi, including Chokakuji Temple, in Asakita Ward, Hiroshima, which contains the remains of an estimated 10-plus people. We believe that to remember the existence of A-bomb victims’ remains represents our vow to pass on stories about the catastrophic disaster caused by the atomic bombings to future generations.

At the end of last year, Nobuko Nakatani, 65, wife of Enryuji Temple’s chief priest, and her oldest son Koin, 36, vice-chief priest, installed a panel next to the Jizo statue that explains about the child victims of the atomic bombing. They hope many visitors to the temple will join hands in front of the Jizo statue to pray for the repose of the souls of deceased children. “We will continue to take good care of their remains.”

(Originally published on February 12, 2020)