Chugoku Shimbun and Nishinippon Shimbun partner on project detailing Hiroshima, Nagasaki’s struggles to preserve A-bombed relics 75 years later

Apr. 20, 2020

by Kyoko Niiyama from Chugoku Shimbun and Tetsuyuki Hanayama from Nagasaki Branch of Nishinippon Shimbun, Staff Writers

In August this year, both Hiroshima and Nagasaki will mark the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings. In terms of efforts undertaken by A-bomb survivors and citizens, as well as methods used to convey the message of nuclear abolition, each of the two cities is surprisingly unaware of the current circumstances and challenges facing the other city. With that in mind, the Chugoku Shimbun and Nishinippon Shimbun, newspapers based in the two A-bombed cities, have launched a joint project to report on topics shared by the two cities from each newspaper’s perspective. The first shared topic comprises “A-bombed structures” and “A-bombed ruins,” which exist despite damage caused by the atomic bombings’ blasts and thermal rays and continue to communicate the tragedy as “silent witnesses.”

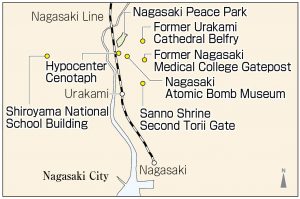

The atomic bomb detonated about 500 meters in the sky above Nagasaki. The Hypocenter Cenotaph, a black granite monument standing directly below the point of the bomb’s explosion, and its surrounding area have been designated a national historic site. In 2016, the Japanese government collectively designated the hypocenter and four A-bombed ruins in Nagasaki—the former Shiroyama National School building, which survived the bombing unscathed; the Sanno Shrine’s second torii gate standing on a single pillar; the former belfry of the Urakami Cathedral; and a gatepost of the former Nagasaki Medical College—as Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Historic Ruins.

In other words, no complete A-bombed structure has been preserved near the hypocenter.

When the Nagasaki City government first began to make efforts to have its A-bombed ruins designated as national historic sites, the staff member in charge of national historic site designation at Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs responded unfavorably. “Only parts of the structures remain. And each is small in scale.” The city interpreted the comment as meaning the structures were indeed living evidence of the atomic bombing, but that they lacked sufficient impact to justify designation by the national government.

To obtain the designation, Nagasaki came up with an explanation based on which the atomic bombing’s damage could be defined as “the area” connecting the hypocenter, from which everything disappeared in the bombing, with the A-bombed ruins that barely managed to survive. The national government agreed to the idea. Tatsuya Shimokawa, chair of the expert committee in Nagasaki and distinguished professor of archeology at Kwassui Women’s University, said, “The only option we had was to find a new perspective for consideration of the ruins.”

The fact was not that few buildings remained after the bombing in Nagasaki. The city has limited flat land, because of its complex geography characterized by mountains pushing against the sea. In the process of reconstruction of the city, many A-bombed buildings were torn down. A symbolic example is the former Urakami Cathedral, which was damaged in the bombing’s blast and completely demolished in 1958. The Catholic Church insisted the cathedral be dismantled because the Church sought a place where believers could gather and worship. The late Tsutomu Tagawa, then mayor of Nagasaki, was willing to preserve the building at first, but later changed his mind. “Tearing down the cathedral can’t be avoided,” he concluded.

Nagasaki finally started putting energy into preserving A-bombed ruins in 1992, triggered by the discovery of an A-bombed exterior wall of the former Nagasaki prison branch in Urakami, near the hypocenter. The prison is known as a place where Chinese nationals confined under suspicion of espionage were killed in the atomic bombing. Around 1992, the citizens began to be concerned about difficulties in passing down the A-bomb survivors’ A-bombing experiences to younger generations because of the survivors’ advancing ages.

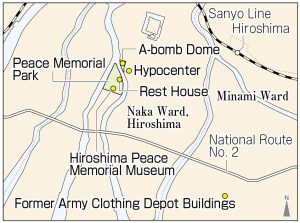

Meanwhile, the other A-bombed city, Hiroshima, has been struggling since last year with the decision about whether to preserve the largest A-bombed structure in that city. The former Army Clothing Depot, located in the city’s Minami Ward, consists of four red-brick buildings with total floor space of about 21,700 square meters. The buildings also serve as an architectural heritage that conveys Hiroshima’s history as a military city.

Chieko Kiriake, 90, a resident of Asaminami Ward, was born and raised near the depot. Her mother worked there. She said, “Amid a roar of sewing machines making military uniforms, many people worked in the buildings.” The depot buildings were located about 2.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. In the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing, the injured were transported to the depot buildings. Several days later, Ms. Kiriake witnessed the scenes inside the building. “I heard constant groaning and crying voices everywhere, and corpses were piled on top of one another in the open courtyard,” she said.

Three of the depot buildings are owned by Hiroshima Prefecture and one by the national government. The increasingly deteriorating site has not been used since 1995. In December last year, for the three buildings it owns, the prefectural government announced a proposal to dismantle two buildings and preserve the external appearance of one. Citizens submitted signatures to the prefecture, calling for preservation all three of the buildings. As a result of the controversy, the site attracted broad attention, with numerous national lawmakers paying the site a visit.

The biggest bottleneck for depot preservation is the expense of anti-seismic construction, which could cost up to 3.3 billion yen per building. Hiroshima City has requested the preservation of all three buildings, but there is no concrete plan for covering the expense. Japan’s national government indicated it would determine how to manage the fourth building based on the prefecture’s results of deliberations.

Iwao Nakanishi, 90, an A-bomb survivor living in the city of Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture, and chair of a citizens group calling for preservation of the former Army Clothing Depot, argued, “Only a small number of people can share with others the tragedy that happened in the depot. It would be too late for regret if these buildings were to be demolished.” Mr. Nakanishi experienced the atomic bombing in the depot when he was a student and mobilized to work there. In February, the prefecture decided to delay by about one year a decision on a policy for managing the buildings and established a department dedicated to studying measures for preserving or utilizing the site.

Currently, both A-bombed cities are faced with a common challenge, which is that the number of A-bombed buildings remaining in the cities has decreased over the years.

In 1996, Nagasaki City identified and listed 137 A-bombed ruins, including structures such as buildings and bridges as well as trees, recognized to have been damaged in the bombing. In 1998, 45 of the ruins were selected by the city for subsidies in support of preservation costs (75 percent of the total cost of up to 30 million yen per year). However, over the 22 years since then, 22 mainly aged, privately owned buildings have disappeared for such reasons as their preservation costs could not be covered.

Yukiyoshi Shirota, 75, an A-bomb survivor and former city official involved in the city’s survey, expressed disappointment. “The relics experienced ‘that day’ and still exist. We have to inform people of that fact,” said Mr. Shirota. Li Huan, professor of regional planning at the Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science, said, “Everyone in the city must engage in more discussion about how A-bombed ruins should be managed, because they can serve as witnesses for future generations.”

Hiroshima City has created separate lists of about 160 A-bombed trees and six A-bombed bridges. Regarding A-bombed buildings, the city kicked off a registration system in 1993 for structures located within five kilometers of the hypocenter. Although some A-bombed buildings have been newly registered recently, such as the Honkawa public restroom, registered in fiscal 2015, and Shinshu Gakuryo, a seminary building for Buddhist education registered last year, 98 buildings were listed in the register in fiscal 1996, a record-high number. Now, the number of registered buildings now totals 86, including the Rest House in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Of the 86 buildings on the list, 64 are privately owned. A staff member of the city’s Peace Promotion Division said, “We really can’t force the owners not to dismantle their A-bombed buildings.” The division has established a system for providing financial support to cover the repair costs and other expenses related to the privately owned A-bombed buildings, amounting to a maximum of 80 million yen for each non-wooden structure and up to 30 million yen for each wooden structure.

How can the huge Army Clothing Depot be preserved? A-bomb survivor Iwao Nakanishi was firm. “Both the government and citizens must discuss and combine our wisdom to resolve the problem. I believe the national government should be involved, since it caused the war in the first place,” he said. There is one precedent by which ruins were preserved after a series of debates. Hiroshima citizens once explained that they did not want to see the A-bomb Dome in Naka Ward, because it made them recall the horrible conditions related to the atomic bombing. However, elementary school and junior high school students launched an initiative for preserving the dome structure that developed into a fund-raising campaign. Permanent preservation of the A-bomb Dome was ultimately finalized 21 years after the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on April 20, 2020)

Nagasaki: Historic site realized by connecting A-bombed ruins in city

Hiroshima: Proposal to dismantle Army Clothing Depot postponed

In August this year, both Hiroshima and Nagasaki will mark the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings. In terms of efforts undertaken by A-bomb survivors and citizens, as well as methods used to convey the message of nuclear abolition, each of the two cities is surprisingly unaware of the current circumstances and challenges facing the other city. With that in mind, the Chugoku Shimbun and Nishinippon Shimbun, newspapers based in the two A-bombed cities, have launched a joint project to report on topics shared by the two cities from each newspaper’s perspective. The first shared topic comprises “A-bombed structures” and “A-bombed ruins,” which exist despite damage caused by the atomic bombings’ blasts and thermal rays and continue to communicate the tragedy as “silent witnesses.”

The atomic bomb detonated about 500 meters in the sky above Nagasaki. The Hypocenter Cenotaph, a black granite monument standing directly below the point of the bomb’s explosion, and its surrounding area have been designated a national historic site. In 2016, the Japanese government collectively designated the hypocenter and four A-bombed ruins in Nagasaki—the former Shiroyama National School building, which survived the bombing unscathed; the Sanno Shrine’s second torii gate standing on a single pillar; the former belfry of the Urakami Cathedral; and a gatepost of the former Nagasaki Medical College—as Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Historic Ruins.

In other words, no complete A-bombed structure has been preserved near the hypocenter.

When the Nagasaki City government first began to make efforts to have its A-bombed ruins designated as national historic sites, the staff member in charge of national historic site designation at Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs responded unfavorably. “Only parts of the structures remain. And each is small in scale.” The city interpreted the comment as meaning the structures were indeed living evidence of the atomic bombing, but that they lacked sufficient impact to justify designation by the national government.

To obtain the designation, Nagasaki came up with an explanation based on which the atomic bombing’s damage could be defined as “the area” connecting the hypocenter, from which everything disappeared in the bombing, with the A-bombed ruins that barely managed to survive. The national government agreed to the idea. Tatsuya Shimokawa, chair of the expert committee in Nagasaki and distinguished professor of archeology at Kwassui Women’s University, said, “The only option we had was to find a new perspective for consideration of the ruins.”

The fact was not that few buildings remained after the bombing in Nagasaki. The city has limited flat land, because of its complex geography characterized by mountains pushing against the sea. In the process of reconstruction of the city, many A-bombed buildings were torn down. A symbolic example is the former Urakami Cathedral, which was damaged in the bombing’s blast and completely demolished in 1958. The Catholic Church insisted the cathedral be dismantled because the Church sought a place where believers could gather and worship. The late Tsutomu Tagawa, then mayor of Nagasaki, was willing to preserve the building at first, but later changed his mind. “Tearing down the cathedral can’t be avoided,” he concluded.

Nagasaki finally started putting energy into preserving A-bombed ruins in 1992, triggered by the discovery of an A-bombed exterior wall of the former Nagasaki prison branch in Urakami, near the hypocenter. The prison is known as a place where Chinese nationals confined under suspicion of espionage were killed in the atomic bombing. Around 1992, the citizens began to be concerned about difficulties in passing down the A-bomb survivors’ A-bombing experiences to younger generations because of the survivors’ advancing ages.

Meanwhile, the other A-bombed city, Hiroshima, has been struggling since last year with the decision about whether to preserve the largest A-bombed structure in that city. The former Army Clothing Depot, located in the city’s Minami Ward, consists of four red-brick buildings with total floor space of about 21,700 square meters. The buildings also serve as an architectural heritage that conveys Hiroshima’s history as a military city.

Chieko Kiriake, 90, a resident of Asaminami Ward, was born and raised near the depot. Her mother worked there. She said, “Amid a roar of sewing machines making military uniforms, many people worked in the buildings.” The depot buildings were located about 2.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. In the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing, the injured were transported to the depot buildings. Several days later, Ms. Kiriake witnessed the scenes inside the building. “I heard constant groaning and crying voices everywhere, and corpses were piled on top of one another in the open courtyard,” she said.

Three of the depot buildings are owned by Hiroshima Prefecture and one by the national government. The increasingly deteriorating site has not been used since 1995. In December last year, for the three buildings it owns, the prefectural government announced a proposal to dismantle two buildings and preserve the external appearance of one. Citizens submitted signatures to the prefecture, calling for preservation all three of the buildings. As a result of the controversy, the site attracted broad attention, with numerous national lawmakers paying the site a visit.

The biggest bottleneck for depot preservation is the expense of anti-seismic construction, which could cost up to 3.3 billion yen per building. Hiroshima City has requested the preservation of all three buildings, but there is no concrete plan for covering the expense. Japan’s national government indicated it would determine how to manage the fourth building based on the prefecture’s results of deliberations.

Iwao Nakanishi, 90, an A-bomb survivor living in the city of Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture, and chair of a citizens group calling for preservation of the former Army Clothing Depot, argued, “Only a small number of people can share with others the tragedy that happened in the depot. It would be too late for regret if these buildings were to be demolished.” Mr. Nakanishi experienced the atomic bombing in the depot when he was a student and mobilized to work there. In February, the prefecture decided to delay by about one year a decision on a policy for managing the buildings and established a department dedicated to studying measures for preserving or utilizing the site.

Privately owned structures gradually disappear

Currently, both A-bombed cities are faced with a common challenge, which is that the number of A-bombed buildings remaining in the cities has decreased over the years.

In 1996, Nagasaki City identified and listed 137 A-bombed ruins, including structures such as buildings and bridges as well as trees, recognized to have been damaged in the bombing. In 1998, 45 of the ruins were selected by the city for subsidies in support of preservation costs (75 percent of the total cost of up to 30 million yen per year). However, over the 22 years since then, 22 mainly aged, privately owned buildings have disappeared for such reasons as their preservation costs could not be covered.

Yukiyoshi Shirota, 75, an A-bomb survivor and former city official involved in the city’s survey, expressed disappointment. “The relics experienced ‘that day’ and still exist. We have to inform people of that fact,” said Mr. Shirota. Li Huan, professor of regional planning at the Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science, said, “Everyone in the city must engage in more discussion about how A-bombed ruins should be managed, because they can serve as witnesses for future generations.”

Hiroshima City has created separate lists of about 160 A-bombed trees and six A-bombed bridges. Regarding A-bombed buildings, the city kicked off a registration system in 1993 for structures located within five kilometers of the hypocenter. Although some A-bombed buildings have been newly registered recently, such as the Honkawa public restroom, registered in fiscal 2015, and Shinshu Gakuryo, a seminary building for Buddhist education registered last year, 98 buildings were listed in the register in fiscal 1996, a record-high number. Now, the number of registered buildings now totals 86, including the Rest House in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Of the 86 buildings on the list, 64 are privately owned. A staff member of the city’s Peace Promotion Division said, “We really can’t force the owners not to dismantle their A-bombed buildings.” The division has established a system for providing financial support to cover the repair costs and other expenses related to the privately owned A-bombed buildings, amounting to a maximum of 80 million yen for each non-wooden structure and up to 30 million yen for each wooden structure.

How can the huge Army Clothing Depot be preserved? A-bomb survivor Iwao Nakanishi was firm. “Both the government and citizens must discuss and combine our wisdom to resolve the problem. I believe the national government should be involved, since it caused the war in the first place,” he said. There is one precedent by which ruins were preserved after a series of debates. Hiroshima citizens once explained that they did not want to see the A-bomb Dome in Naka Ward, because it made them recall the horrible conditions related to the atomic bombing. However, elementary school and junior high school students launched an initiative for preserving the dome structure that developed into a fund-raising campaign. Permanent preservation of the A-bomb Dome was ultimately finalized 21 years after the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on April 20, 2020)