One year after the renewal of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (Part 1): Far from reality

May 15, 2020

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

On April 25, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in downtown Hiroshima will mark the first anniversary of the reopening of its main building after renovation. An exhibit that focused on actual artifacts, including personal belongings, drew much attention and the number of visitors to the museum in fiscal year 2019 marked a record high. While the museum crowded with many visitors, conveying the reality of the atomic bombing of 75 years ago is fundamentally difficult, as is clear when atomic-bomb survivors say, “Only those who experienced the atomic bombing can understand it.” In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun will explore the current ways the Peace Memorial Museum addresses this difficulty.

The first items visitors see in the main building of the museum are “collective displays.” On display inside a large glass case are the personal belongings of 23 students who were mobilized to work for the war effort and were killed when the city was attacked with the atomic bomb.

On one piece of the charred white cloth are small embroidered letters, “Marumi.” It is a torn piece of a blouse worn by Yoshiko Marumi, then 14 years old and a second-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School). It was put on a permanent display for the first time when the main building was renovated.

Yumiko Umino, 61, a relative of Ms. Marumi, and a resident of Minami Ward, learned about her from her mother and her aunt, both cousins of Ms. Marumi. She said, “I heard Yoshiko was always wearing pretty clothes. She must have been very well taken care of,” turning her thoughts to Yoshiko.

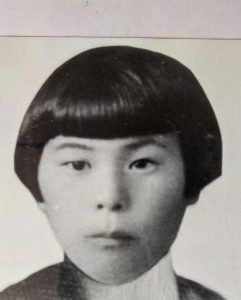

Yoshiko’s photograph was provided by Ms. Umino, who visited the museum after it reopened. It was held in the home of Yoshiko’s late father, Shigeo. Ms. Umino verified Yoshiko’s birthday in her family register and confirmed she was 14 years old when she died, which had previously been unclear.

Yoshiko was the only daughter of a liquor store owner. The store was located in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward). She was one of the 541 first- and second-year students at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School mobilized to tear down homes to create fire lanes south of what is now Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Naka Ward, and perished in the blast on August 6, 1945. A few days later, her father, Shigeo, who had been searching for her, found that she and several her classmates had died at the foot of the bridge nearby. He was able to recognize his daughter from the embroidery of her blouse that had been left behind after the blaze.

Shigeo had not talked a lot about the memento until he died at the age of 77 in 1982. Ms. Umino said, “I don’t have much I can say about Yoshiko, but this small piece of her blouse that remains speaks something to me.” Each of the personal belongings conveys the last message about the person’s death. She hopes many people will feel the weight of displaying real artifacts and see them.

A father of Yoshiko’s classmate wrote about how the area surrounding the current Peace Bridge was by his account. “Dozens, or hundreds, of girls and others are mercilessly all over the riversides near a sandbank. Some are injured or sleeping, actually dead, and others are lying here and there, slightly writhing. I hear groans of the victims.” (From Floating Lantern published in 1957)

The intention of a collective display of personal belongings is to have visitors imagine such a catastrophic condition. The displays that follow, also have photographs and short explanations of the victims—allowing visitors use their imagination.

In Peace Memorial Museum, some visitors say, “I felt as if what I saw were my own experiences,” and “I felt empathy with the feelings of the family members of A-bomb victims.” Hironobu Ochiba, 42, the chief curator of the museum, said, “Our intention to have visitors feel A-bomb victims as each and every person is conveyed.”

Hiroshi Harada, 80, a former director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and A-bomb survivor living in Asaminami Ward, said, “The exhibit is sophisticated, but it is far from reality.” People suffered burns from the atomic bomb’s thermal waves, and the stench of death was lingering all around. He said, “The word ‘empathy’ is not suitable. It is difficult to tell people who did not experience the atomic bombing to imagine it.” Photographs of A-bomb survivors and drawings of the atomic bombing made by them are displayed, but he requires that there should be more exhibits that exactly convey the horrors of war.

Mr. Harada shares his own A-bomb account with others. He knows how difficult it is to convey the reality of it to people, so his strict requirements can be interpreted as the flip side of his expectation. He said, “The Peace Memorial Museum serves as a brake to guarantee that nuclear weapons will never be used again. The exhibit need not be sophisticated; an unpolished exhibit would be fine, too. I hope the museum will pursue a limit of conveying the horrors of that day.” How to convey what happened on August 6, 1945, is a question the museum continues to ask after the museum reopened.

(Originally published on April 24, 2020)

On April 25, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in downtown Hiroshima will mark the first anniversary of the reopening of its main building after renovation. An exhibit that focused on actual artifacts, including personal belongings, drew much attention and the number of visitors to the museum in fiscal year 2019 marked a record high. While the museum crowded with many visitors, conveying the reality of the atomic bombing of 75 years ago is fundamentally difficult, as is clear when atomic-bomb survivors say, “Only those who experienced the atomic bombing can understand it.” In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun will explore the current ways the Peace Memorial Museum addresses this difficulty.

Focusing on personal belongings resonates in the heart

The first items visitors see in the main building of the museum are “collective displays.” On display inside a large glass case are the personal belongings of 23 students who were mobilized to work for the war effort and were killed when the city was attacked with the atomic bomb.

Put on a permanent display for the first time

On one piece of the charred white cloth are small embroidered letters, “Marumi.” It is a torn piece of a blouse worn by Yoshiko Marumi, then 14 years old and a second-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School). It was put on a permanent display for the first time when the main building was renovated.

Yumiko Umino, 61, a relative of Ms. Marumi, and a resident of Minami Ward, learned about her from her mother and her aunt, both cousins of Ms. Marumi. She said, “I heard Yoshiko was always wearing pretty clothes. She must have been very well taken care of,” turning her thoughts to Yoshiko.

Yoshiko’s photograph was provided by Ms. Umino, who visited the museum after it reopened. It was held in the home of Yoshiko’s late father, Shigeo. Ms. Umino verified Yoshiko’s birthday in her family register and confirmed she was 14 years old when she died, which had previously been unclear.

Yoshiko was the only daughter of a liquor store owner. The store was located in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward). She was one of the 541 first- and second-year students at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School mobilized to tear down homes to create fire lanes south of what is now Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Naka Ward, and perished in the blast on August 6, 1945. A few days later, her father, Shigeo, who had been searching for her, found that she and several her classmates had died at the foot of the bridge nearby. He was able to recognize his daughter from the embroidery of her blouse that had been left behind after the blaze.

Shigeo had not talked a lot about the memento until he died at the age of 77 in 1982. Ms. Umino said, “I don’t have much I can say about Yoshiko, but this small piece of her blouse that remains speaks something to me.” Each of the personal belongings conveys the last message about the person’s death. She hopes many people will feel the weight of displaying real artifacts and see them.

A father of Yoshiko’s classmate wrote about how the area surrounding the current Peace Bridge was by his account. “Dozens, or hundreds, of girls and others are mercilessly all over the riversides near a sandbank. Some are injured or sleeping, actually dead, and others are lying here and there, slightly writhing. I hear groans of the victims.” (From Floating Lantern published in 1957)

The intention of a collective display of personal belongings is to have visitors imagine such a catastrophic condition. The displays that follow, also have photographs and short explanations of the victims—allowing visitors use their imagination.

In Peace Memorial Museum, some visitors say, “I felt as if what I saw were my own experiences,” and “I felt empathy with the feelings of the family members of A-bomb victims.” Hironobu Ochiba, 42, the chief curator of the museum, said, “Our intention to have visitors feel A-bomb victims as each and every person is conveyed.”

There is no end to asking questions

Hiroshi Harada, 80, a former director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and A-bomb survivor living in Asaminami Ward, said, “The exhibit is sophisticated, but it is far from reality.” People suffered burns from the atomic bomb’s thermal waves, and the stench of death was lingering all around. He said, “The word ‘empathy’ is not suitable. It is difficult to tell people who did not experience the atomic bombing to imagine it.” Photographs of A-bomb survivors and drawings of the atomic bombing made by them are displayed, but he requires that there should be more exhibits that exactly convey the horrors of war.

Mr. Harada shares his own A-bomb account with others. He knows how difficult it is to convey the reality of it to people, so his strict requirements can be interpreted as the flip side of his expectation. He said, “The Peace Memorial Museum serves as a brake to guarantee that nuclear weapons will never be used again. The exhibit need not be sophisticated; an unpolished exhibit would be fine, too. I hope the museum will pursue a limit of conveying the horrors of that day.” How to convey what happened on August 6, 1945, is a question the museum continues to ask after the museum reopened.

(Originally published on April 24, 2020)