Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Recreating cityscapes of Hondori shopping arcade, Part 1: A barber’s photo albums

Jan. 3, 2020

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

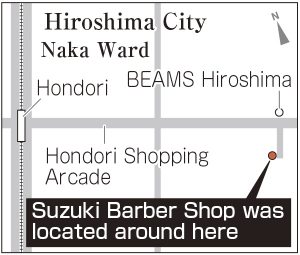

With his heart swelling with emotion about a family of six who lived in the Suzuki Barber Shop, Tsuneaki Suzuki, 88, a resident of Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima, stands on a street to the south of the clothing store BEAMS Hiroshima in the Hondori shopping arcade, which runs to the east and west in downtown Hiroshima. The Suzuki Barber Shop was located on the west side of this street until 75 years ago. “The familiy was really close.”

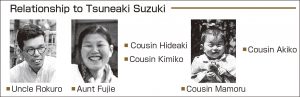

The barber shop was run by Tsuneaki’s uncle, Rokuro Suzuki. Tsuneaki himself lived to the east of Hiroshima Station, about two kilometers from the barber shop. But he went to Fukuro-machi Elementary School nearby, and often dropped in at the shop on his way home. They were like family to him. Tsuneaki used to play with Hideaki, one of his cousins who was two grades below him, drawing pictures on the street in front of the shop and playing sumo.

Rokuro, “a kind-hearted man who treated children and animals affectionately,” liked photography. He often aimed his camera at children playing in front of his shop, and took their photos. He also recorded the growth of his children in his albums: “Stood up for the first time” and “Starting the first grade,” were some of the descriptions. For a photo in which Hideaki, his oldest son, scooped up shrimp in a river with other children, Rokuro wrote, “He is just like me in my childhood.”

On the day before “that day,” Hideaki, a sixth grader at Fukuro-machi Elementary School, was enjoying catching shrimp in the river. Tsuneaki, then a second-year student at the Junior High School attached to Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now Hiroshima University Junior and Senior High School, located in Minami Ward), played with him as always. “See you later,” they said to each other, as they were planning to play together again.

The next morning, Hideaki experienced the atomic bombing inside the Fukuro-machi Elementary School. He fled to a first-aid station with his younger sister in the third grade, Kimiko, on his back. She had also been in the school and suffered serious burns. Hideaki said to Kimiko, “I’ll be back to get you. Wait here.” As Hideaki left to seek help, Kimiko, with labored breathing, said, “Get revenge for me.” Her whereabouts after that are unknown.

Hideaki was able to meet up with his relatives. But he died about a week after suffering from a high fever and bleeding. Rokuro, then 43, died where he had been transported. His second son, Mamoru, 3, and his second daughter, Akiko, 1, were found as remains in the burned ruins of his shop. His wife, Fujie, 33, having suffered serious injuries, found her way to a relative’s house. But she threw herself into a well after she learned that her husband and four children seemed to have died.

At least ten albums containing about 2,000 photographs remain as proof that the perished family had once lived. Maybe because the family cherished these albums, they had been taken to Tsuneaki’s house, some distance from the city center, before the atomic bombing.

“They vanished as if a candle had been blown out,” said Tsuneaki, an A-bomb survivor who was at home at the time of the atomic bombing. Prior to the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombing, he took up a pen, drew a picture, and wrote descriptions about the annihilation of Rokuro’s family. When his picture was stored by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in downtown Hiroshima as one of the drawings of the atomic bombing created by A-bomb survivors, the existence of the photographs in Tsuneaki’s possession also came to light.

The photographs show Hideaki and Kimiko playing with dolls or the entire family holding hands. The albums remained as if defying the atomic bombing to wipe out the record of their lives. In 2014, Tsuneaki provided the image data of these photographs to the museum. The museum showed a portion of the photographs in an exhibit, which was well received.

Kayo Takahashi, a curator at the museum in charge of the exhibit, realized “the importance of conveying the ‘lives,’ taken by the atomic bombing.” Her realization is similar with Tsuneaki’s wishes for the young people traveling along the street where the barber shop had been located. “I want them to know that Uncle Rokuro and his family lived here.”

(Originally published on January 3, 2020)

Photos depict perished family

2,000 photographs remain to tell their story

With his heart swelling with emotion about a family of six who lived in the Suzuki Barber Shop, Tsuneaki Suzuki, 88, a resident of Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima, stands on a street to the south of the clothing store BEAMS Hiroshima in the Hondori shopping arcade, which runs to the east and west in downtown Hiroshima. The Suzuki Barber Shop was located on the west side of this street until 75 years ago. “The familiy was really close.”

The barber shop was run by Tsuneaki’s uncle, Rokuro Suzuki. Tsuneaki himself lived to the east of Hiroshima Station, about two kilometers from the barber shop. But he went to Fukuro-machi Elementary School nearby, and often dropped in at the shop on his way home. They were like family to him. Tsuneaki used to play with Hideaki, one of his cousins who was two grades below him, drawing pictures on the street in front of the shop and playing sumo.

Children’s growth also recorded

Rokuro, “a kind-hearted man who treated children and animals affectionately,” liked photography. He often aimed his camera at children playing in front of his shop, and took their photos. He also recorded the growth of his children in his albums: “Stood up for the first time” and “Starting the first grade,” were some of the descriptions. For a photo in which Hideaki, his oldest son, scooped up shrimp in a river with other children, Rokuro wrote, “He is just like me in my childhood.”

On the day before “that day,” Hideaki, a sixth grader at Fukuro-machi Elementary School, was enjoying catching shrimp in the river. Tsuneaki, then a second-year student at the Junior High School attached to Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now Hiroshima University Junior and Senior High School, located in Minami Ward), played with him as always. “See you later,” they said to each other, as they were planning to play together again.

The next morning, Hideaki experienced the atomic bombing inside the Fukuro-machi Elementary School. He fled to a first-aid station with his younger sister in the third grade, Kimiko, on his back. She had also been in the school and suffered serious burns. Hideaki said to Kimiko, “I’ll be back to get you. Wait here.” As Hideaki left to seek help, Kimiko, with labored breathing, said, “Get revenge for me.” Her whereabouts after that are unknown.

Hideaki was able to meet up with his relatives. But he died about a week after suffering from a high fever and bleeding. Rokuro, then 43, died where he had been transported. His second son, Mamoru, 3, and his second daughter, Akiko, 1, were found as remains in the burned ruins of his shop. His wife, Fujie, 33, having suffered serious injuries, found her way to a relative’s house. But she threw herself into a well after she learned that her husband and four children seemed to have died.

At least ten albums containing about 2,000 photographs remain as proof that the perished family had once lived. Maybe because the family cherished these albums, they had been taken to Tsuneaki’s house, some distance from the city center, before the atomic bombing.

Exhibit well received

“They vanished as if a candle had been blown out,” said Tsuneaki, an A-bomb survivor who was at home at the time of the atomic bombing. Prior to the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombing, he took up a pen, drew a picture, and wrote descriptions about the annihilation of Rokuro’s family. When his picture was stored by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in downtown Hiroshima as one of the drawings of the atomic bombing created by A-bomb survivors, the existence of the photographs in Tsuneaki’s possession also came to light.

The photographs show Hideaki and Kimiko playing with dolls or the entire family holding hands. The albums remained as if defying the atomic bombing to wipe out the record of their lives. In 2014, Tsuneaki provided the image data of these photographs to the museum. The museum showed a portion of the photographs in an exhibit, which was well received.

Kayo Takahashi, a curator at the museum in charge of the exhibit, realized “the importance of conveying the ‘lives,’ taken by the atomic bombing.” Her realization is similar with Tsuneaki’s wishes for the young people traveling along the street where the barber shop had been located. “I want them to know that Uncle Rokuro and his family lived here.”

(Originally published on January 3, 2020)