Life and death of a Hiroshima Girl, Part 2: Medical treatment in the U.S.

Aug. 4, 2019

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

On May 9, 1955, a U.S. Air Force C-54 plane with a group of young, unmarried women on board — A-bomb survivors from Hiroshima — landed at a U.S. military air base outside New York.

The headline of an article that appeared in the May 10 issue of The New York Times read:

HIROSHIMA GIRLS HERE FOR SURGERY

Twenty-five Japanese girls who bear the scars of the world's first atom bomb attack, arrived here yesterday hoping that American medical science might erase the blemishes and restore them to normal.

The article, which was accompanied by three photos of the women, including one that showed them lined up in front of the hospital in a city of skyscrapers, provided a great deal of exposure to their arrival.

Included in the article was a speech made by a 29-year-old woman (she died in 1995), who was the representative of the group, and remarks made by a 23-year-old woman who was working as a tailor of women’s clothing (she died in 2017). Details of the project were also explained: “The Friends Center (a pacifist Quaker group) is responsible for arranging homestay accommodation for the women, one pair per family, and looking after them during their stay.”

The 23-year-old woman referred to the damage caused by the atomic bomb, saying, “The Japanese Navy took the first step in the last war," and “We in Hiroshima had a terrible destruction upon us, but we should have repentance rather than hatred, and we began to hate war."

Back then, the United States was carrying out a number of hydrogen bomb tests in the southern Pacific Ocean, and there were some people who regarded any opposition to the atomic and hydrogen bombs as “a plot by the communists.” In fact, the U.S. State Department made efforts to block the visit to the United States by the young A-bomb survivors from Hiroshima.

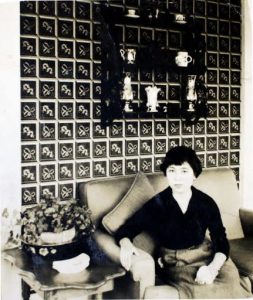

According to a diary entry written by Tomoko Nakabayashi, who was then 26, on May 10, the day after they arrived in the United States, the women were taken to a Quaker training facility. They were given English conversation lessons and dance lessons. They also performed, in kimono, a dance to the song “Tanko Bushi” (a traditional Japanese coal mining folk tune). On May 24, two of the women went to the hospital, and the host families of the remaining 23 women came to the training facility to pick up the women and take them to their homes. The home which Tomoko went to belonged to a banker and had a pool, but she felt uneasy. She wrote in her diary, “I find myself in a world in which I don’t understand the language.” As a rule, all the women were required to move to a different family each month.

Detailed account after surgery

Tomoko underwent plastic surgery on the back of her right hand and arm on August 16, and was discharged from the hospital on September 18. Although her fingers were still swollen, she picked up a pen and wrote a four-page letter to her sister in which she said, “I was under general anesthesia during the operation, so I didn’t know what was happening to my body. Because large areas of skin were taken from three sections of my left thigh, I couldn’t even walk.” Her sister, who was one year older, was back in Tokyo for her wedding.

Tomoko’s sister, Eiko Shinohara, 91, is a resident of Mitaka, Tokyo, and still cherishes Tomoko’s letter. She remembers that Tomoko recovered from the physical and psychological effects of the atomic bomb because of the goodwill and actions of the people who supported the Hiroshima Girls.

Tomoko wrote in her letter to Eiko that she had met many people at various parties held by Norman Cousins, among others, who spearheaded the treatment project for the A-bomb women survivors (he died in 1990 at the age of 75), and that she felt overjoyed when her host family told her that she was pretty. (The letter was mailed on November 16, 1955.)

Tomoko underwent a second surgery on her left hand on January 5, 1956.

She also expressed her hopes for her recovery in another letter to her sister (mailed on February 9, 1956), saying, “The operation was such a great success that my friends were surprised at the results and were overcome with joy. I might be able to extend my fingers, which have been bent for the past 10 years, if I gradually do rehabilitation exercises.”

Operating surgeons were former military doctors

The hospital provided two rooms for the women, exclusively for their use. Not only Quakers, but also Japanese descendants who had been sent to internment camps in the United States during World War II, visited the women in the hospital. The three surgeons who performed the operations served as military doctors on the battlefields of Europe during the war.

“We treated people on the battlefields who had been badly wounded and so we agreed to treat the young Japanese women, hoping to make use of our experience,” said Dr. Bernard Simon to a Chugoku Shimbun reporter during an interview with the media when he was reunited with four of the Hiroshima Girls in New York in 1996. (Dr. Bernard died in 1999 at the age of 87.)

In the letter Tomoko sent to her sister after her second surgery, she wrote, “I think I’ve finished all the operations that I’m supposed to have.” In another letter mailed to her sister on April 30, she shared her idea of studying abroad, saying, “I’m going to meet some teachers next week and talk to them so I can get their advice.” She wanted to study at a dressmaking school in America to become a hat designer.

A good letter writer, Tomoko often wrote to her parents and sisters, who were waiting for her to return to their home in Hakushimakita-machi (now part of Naka Ward, Hiroshima). But then, suddenly, the news of her death reached them.

(Originally published on August 4, 2019)

Goodwill of Americans heals emotional wounds and gives hope

On May 9, 1955, a U.S. Air Force C-54 plane with a group of young, unmarried women on board — A-bomb survivors from Hiroshima — landed at a U.S. military air base outside New York.

The headline of an article that appeared in the May 10 issue of The New York Times read:

HIROSHIMA GIRLS HERE FOR SURGERY

Twenty-five Japanese girls who bear the scars of the world's first atom bomb attack, arrived here yesterday hoping that American medical science might erase the blemishes and restore them to normal.

The article, which was accompanied by three photos of the women, including one that showed them lined up in front of the hospital in a city of skyscrapers, provided a great deal of exposure to their arrival.

Included in the article was a speech made by a 29-year-old woman (she died in 1995), who was the representative of the group, and remarks made by a 23-year-old woman who was working as a tailor of women’s clothing (she died in 2017). Details of the project were also explained: “The Friends Center (a pacifist Quaker group) is responsible for arranging homestay accommodation for the women, one pair per family, and looking after them during their stay.”

The 23-year-old woman referred to the damage caused by the atomic bomb, saying, “The Japanese Navy took the first step in the last war," and “We in Hiroshima had a terrible destruction upon us, but we should have repentance rather than hatred, and we began to hate war."

Back then, the United States was carrying out a number of hydrogen bomb tests in the southern Pacific Ocean, and there were some people who regarded any opposition to the atomic and hydrogen bombs as “a plot by the communists.” In fact, the U.S. State Department made efforts to block the visit to the United States by the young A-bomb survivors from Hiroshima.

According to a diary entry written by Tomoko Nakabayashi, who was then 26, on May 10, the day after they arrived in the United States, the women were taken to a Quaker training facility. They were given English conversation lessons and dance lessons. They also performed, in kimono, a dance to the song “Tanko Bushi” (a traditional Japanese coal mining folk tune). On May 24, two of the women went to the hospital, and the host families of the remaining 23 women came to the training facility to pick up the women and take them to their homes. The home which Tomoko went to belonged to a banker and had a pool, but she felt uneasy. She wrote in her diary, “I find myself in a world in which I don’t understand the language.” As a rule, all the women were required to move to a different family each month.

Detailed account after surgery

Tomoko underwent plastic surgery on the back of her right hand and arm on August 16, and was discharged from the hospital on September 18. Although her fingers were still swollen, she picked up a pen and wrote a four-page letter to her sister in which she said, “I was under general anesthesia during the operation, so I didn’t know what was happening to my body. Because large areas of skin were taken from three sections of my left thigh, I couldn’t even walk.” Her sister, who was one year older, was back in Tokyo for her wedding.

Tomoko’s sister, Eiko Shinohara, 91, is a resident of Mitaka, Tokyo, and still cherishes Tomoko’s letter. She remembers that Tomoko recovered from the physical and psychological effects of the atomic bomb because of the goodwill and actions of the people who supported the Hiroshima Girls.

Tomoko wrote in her letter to Eiko that she had met many people at various parties held by Norman Cousins, among others, who spearheaded the treatment project for the A-bomb women survivors (he died in 1990 at the age of 75), and that she felt overjoyed when her host family told her that she was pretty. (The letter was mailed on November 16, 1955.)

Tomoko underwent a second surgery on her left hand on January 5, 1956.

She also expressed her hopes for her recovery in another letter to her sister (mailed on February 9, 1956), saying, “The operation was such a great success that my friends were surprised at the results and were overcome with joy. I might be able to extend my fingers, which have been bent for the past 10 years, if I gradually do rehabilitation exercises.”

Operating surgeons were former military doctors

The hospital provided two rooms for the women, exclusively for their use. Not only Quakers, but also Japanese descendants who had been sent to internment camps in the United States during World War II, visited the women in the hospital. The three surgeons who performed the operations served as military doctors on the battlefields of Europe during the war.

“We treated people on the battlefields who had been badly wounded and so we agreed to treat the young Japanese women, hoping to make use of our experience,” said Dr. Bernard Simon to a Chugoku Shimbun reporter during an interview with the media when he was reunited with four of the Hiroshima Girls in New York in 1996. (Dr. Bernard died in 1999 at the age of 87.)

In the letter Tomoko sent to her sister after her second surgery, she wrote, “I think I’ve finished all the operations that I’m supposed to have.” In another letter mailed to her sister on April 30, she shared her idea of studying abroad, saying, “I’m going to meet some teachers next week and talk to them so I can get their advice.” She wanted to study at a dressmaking school in America to become a hat designer.

A good letter writer, Tomoko often wrote to her parents and sisters, who were waiting for her to return to their home in Hakushimakita-machi (now part of Naka Ward, Hiroshima). But then, suddenly, the news of her death reached them.

(Originally published on August 4, 2019)