Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Recreating cityscapes: Honkawa area, full of life, with children and craftspeople

Apr. 14, 2020

by Miho Kuwajima and Kyoko Niiyama, Staff Writers

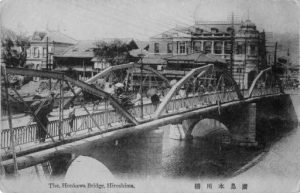

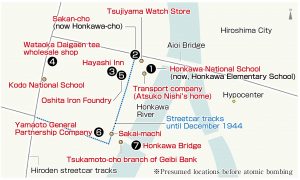

Before World War II, Hiroshima’s Honkawa area, which lies at the west end of Aioi Bridge, included the neighborhoods Kajiya-cho (Blacksmiths’ town), Sakan-cho (Plasterers’ town), Aburaya-cho (Oil merchants’ town), and others. As their names imply, these neighborhoods were home to wholesalers, shops, banks, and small factories. On August 6, 1945, the U.S. military dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, targeting the T-shaped bridge. Most residents were killed instantly. The Honkawa National School (now Honkawa Elementary School), the school closest to the hypocenter, was completely destroyed. Some photographs miraculously survived the atomic bombing and have been kept carefully by former residents of the area and victims’ families. The photos convey to our present time stories of people’s lives as they lived before the atomic bombing.

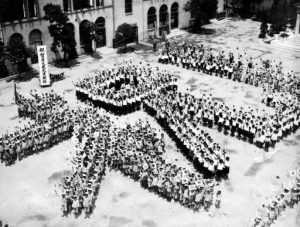

Lines of students at the Honkawa National School formed the shape of a Chinese character meaning “celebration,” with each of the students holding up a national flag of Japan. This photo was taken during an event to celebrate a local politician’s assumption of office as the nation’s minister of finance in 1937. The photo conveys the excitement of the school as well as of those times, when civilians were mobilized to promote national policies.

This photo also shows arch-shaped windows that were unique characteristics of the school building, constructed in Kajiya-cho (now Honkawa-cho) in 1928. It was the first ferroconcrete public elementary school building in Hiroshima. “The windows were stylish. Ms. Kiyoko Endo, the teacher in charge of the first-graders, was good at the organ, and I admired her,” said Atsuko Nishi (nee Tokuda), 83, a resident of the city’s Nishi Ward.

Ms. Nishi started attending the school in 1943. Her home was located diagonally across from the school’s front gate. Her father ran a transport company. “Our house was next to a liquor store and across from a commercial inn. Children often visited each other’s homes and had meals together. It was a nice neighborhood,” she said.

However, with increasing numbers of air raids on Japan, in April 1945, about 700 of the school’s more than 1,000 students evacuated outside the city in groups or to relatives’ homes. Ms. Nishi moved to the former village of Minochi (now Saeki Ward), her father’s birthplace. Around June, her original home near the school was demolished to create a lane for fire-prevention. Around that time, her parents moved closer to the west end of Aioi Bridge.

With the school located as close as 350 meters from the hypocenter, only the outer frame of the school building remained and everything else was incinerated that day, August 6. Countless bodies of victims were brought to the school, turning it into a crematorium, in what must have been a gruesome sight. According to the Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, at least 218 students who had not moved out of town died that day. Ms. Endo, Ms. Nishi’s favorite teacher, also died.

Ms. Nishi lost her mother in the atomic bombing. When she went back to school in December, “The basement of the school was laid bare. When playing hide-and-seek with friends, I came across a skull.” Part of the school building today is used as the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum.

Because of the atomic bombing, more than 80 percent of the residents in the area died and many children were orphaned. The parents of Tokumu Oshita, 86, ran an iron foundry in Sakan-cho (now Honkawa-cho). Mr. Oshita, a resident of Naka Ward, was a sixth grader at the Kodo National School. While he was evacuated to the present-day Shijihara area of the town of Kitahiroshima, his parents and relatives died in the atomic bombing.

Mr. Oshita said his parents’ iron foundry “received orders from the navy and operated until 10 at night every day.” When he came back to the iron foundry one week after the atomic bombing, he found it had been obliterated, with “only the bodies of about five people lying around burned machines.” In 1949, his uncle and others rebuilt the iron foundry, which Mr. Oshita later took over. “When I think of the atomic bombing, I can’t carry on business. I tried to blot out the memory and didn’t tell anyone about it,” he said.

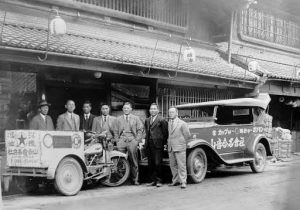

Nishi Kuken-cho (now Tokaichi-machi) used to be a wholesale district. At the Wataoka Daigaen tea wholesale shop, Shigemi Wataoka, then 45, and his wife Mitsuko, 38, died in the atomic bombing along with their three-and six-year-old daughters. The couple’s second daughter, who was 12 at the time, also died as she was helping tear down buildings to create fire lanes. Only their oldest daughter Chizuko, who was 16, survived (she died at age 82 in 2011). Her daughter, Miho Iwata (nee Wataoka), 62, still runs the iron foundry in its same location before the atomic bombing.

About 15 years ago, Ms. Iwata began to serve as a volunteer guide at the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum. She has been speaking about her mother’s A-bombing experience to students on school trips. On display at her iron foundry today are photos of her grandparents working energetically and of their family taken the day before the atomic bombing. She said, “I want people to know what kind of stores were here and what happened in the atomic bombing. Hiroshima is not some ancient tale; it happened amid everyday life.”

(Originally published on April 14, 2020)

Before World War II, Hiroshima’s Honkawa area, which lies at the west end of Aioi Bridge, included the neighborhoods Kajiya-cho (Blacksmiths’ town), Sakan-cho (Plasterers’ town), Aburaya-cho (Oil merchants’ town), and others. As their names imply, these neighborhoods were home to wholesalers, shops, banks, and small factories. On August 6, 1945, the U.S. military dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, targeting the T-shaped bridge. Most residents were killed instantly. The Honkawa National School (now Honkawa Elementary School), the school closest to the hypocenter, was completely destroyed. Some photographs miraculously survived the atomic bombing and have been kept carefully by former residents of the area and victims’ families. The photos convey to our present time stories of people’s lives as they lived before the atomic bombing.

Stylish school and favored teacher—Atomic bomb turns school into crematorium

Lines of students at the Honkawa National School formed the shape of a Chinese character meaning “celebration,” with each of the students holding up a national flag of Japan. This photo was taken during an event to celebrate a local politician’s assumption of office as the nation’s minister of finance in 1937. The photo conveys the excitement of the school as well as of those times, when civilians were mobilized to promote national policies.

This photo also shows arch-shaped windows that were unique characteristics of the school building, constructed in Kajiya-cho (now Honkawa-cho) in 1928. It was the first ferroconcrete public elementary school building in Hiroshima. “The windows were stylish. Ms. Kiyoko Endo, the teacher in charge of the first-graders, was good at the organ, and I admired her,” said Atsuko Nishi (nee Tokuda), 83, a resident of the city’s Nishi Ward.

Ms. Nishi started attending the school in 1943. Her home was located diagonally across from the school’s front gate. Her father ran a transport company. “Our house was next to a liquor store and across from a commercial inn. Children often visited each other’s homes and had meals together. It was a nice neighborhood,” she said.

However, with increasing numbers of air raids on Japan, in April 1945, about 700 of the school’s more than 1,000 students evacuated outside the city in groups or to relatives’ homes. Ms. Nishi moved to the former village of Minochi (now Saeki Ward), her father’s birthplace. Around June, her original home near the school was demolished to create a lane for fire-prevention. Around that time, her parents moved closer to the west end of Aioi Bridge.

With the school located as close as 350 meters from the hypocenter, only the outer frame of the school building remained and everything else was incinerated that day, August 6. Countless bodies of victims were brought to the school, turning it into a crematorium, in what must have been a gruesome sight. According to the Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb War Disaster, at least 218 students who had not moved out of town died that day. Ms. Endo, Ms. Nishi’s favorite teacher, also died.

Ms. Nishi lost her mother in the atomic bombing. When she went back to school in December, “The basement of the school was laid bare. When playing hide-and-seek with friends, I came across a skull.” Part of the school building today is used as the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum.

Because of the atomic bombing, more than 80 percent of the residents in the area died and many children were orphaned. The parents of Tokumu Oshita, 86, ran an iron foundry in Sakan-cho (now Honkawa-cho). Mr. Oshita, a resident of Naka Ward, was a sixth grader at the Kodo National School. While he was evacuated to the present-day Shijihara area of the town of Kitahiroshima, his parents and relatives died in the atomic bombing.

Mr. Oshita said his parents’ iron foundry “received orders from the navy and operated until 10 at night every day.” When he came back to the iron foundry one week after the atomic bombing, he found it had been obliterated, with “only the bodies of about five people lying around burned machines.” In 1949, his uncle and others rebuilt the iron foundry, which Mr. Oshita later took over. “When I think of the atomic bombing, I can’t carry on business. I tried to blot out the memory and didn’t tell anyone about it,” he said.

Nishi Kuken-cho (now Tokaichi-machi) used to be a wholesale district. At the Wataoka Daigaen tea wholesale shop, Shigemi Wataoka, then 45, and his wife Mitsuko, 38, died in the atomic bombing along with their three-and six-year-old daughters. The couple’s second daughter, who was 12 at the time, also died as she was helping tear down buildings to create fire lanes. Only their oldest daughter Chizuko, who was 16, survived (she died at age 82 in 2011). Her daughter, Miho Iwata (nee Wataoka), 62, still runs the iron foundry in its same location before the atomic bombing.

About 15 years ago, Ms. Iwata began to serve as a volunteer guide at the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum. She has been speaking about her mother’s A-bombing experience to students on school trips. On display at her iron foundry today are photos of her grandparents working energetically and of their family taken the day before the atomic bombing. She said, “I want people to know what kind of stores were here and what happened in the atomic bombing. Hiroshima is not some ancient tale; it happened amid everyday life.”

(Originally published on April 14, 2020)