Chugoku Shimbun and Nishinippon Shimbun partner to detail why some who experienced A-bombing are ineligible for A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate

May 25, 2020

by Miho Kuwajima from Chugoku Shimbun and Eiko Tokumasu from Nagasaki Branch of Nishinippon Shimbun, Staff Writers

Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificates are issued to people who directly experienced the atomic bombing within designated areas, those exposed to residual radiation after entering the city center within two weeks of the bombings, and those exposed to radiation while administering aid to others. However, people who experienced the atomic bombing not falling under those categories have continued their appeal for recognition as hibakusha (A-bomb survivors). In Nagasaki, boundaries were drawn to determine eligibility for aid as A-bomb survivors in accordance with governmental administrative districts. Meanwhile, in Hiroshima, “black rain” is said to have fallen broadly. By focusing on issues specific to each city, the two newspapers herein shed light on the current conditions surrounding these issues in the two A-bombed cities.

Chiyoko Iwanaga, 84, a former elementary school teacher living in Nagasaki City, gave an explanation with hand outstretched. The area in front of the wall near where she stood is a neighborhood known as Sueishi-machi, and on the other side of the wall is Fukahori-machi. At that time, 75 years ago, Sueishi-machi was part of Nagasaki City, and Fukahori-machi was a village.

On August 9, 1945, when she was nine years old, Ms. Iwanaga was overwhelmed by the flash and blast of the atomic bombing. One week later, she bled from her gums and had pain and a feeling of pressure in her throat. At the time of the bombing, she was in the former village of Fukahori-mura. Unlike people who were in the neighborhood of Sueishi-machi, which was located within the Nagasaki city limits, she has not been officially recognized as a hibakusha. “Why haven’t I been designated even though I was the same distance from the hypocenter as other A-bomb survivors,” she said.

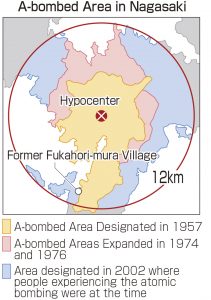

In Nagasaki, whether someone is hibakusha has generally been determined by the administrative district where he or she was at the time of the bombing. The so-called “A-bombed area” in Nagasaki is an uneven oval shape stretching 24.9 kilometers north and south and 13.9 kilometers east and west. The area was expanded in 1974 and 1976, including one part for which people in the area at the time of the bombing could obtain an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate after undergoing a health examination at national government expense, similar to the survivors in Hiroshima who were in “heavy rain areas.”

About a half century after the atomic bombing, Nagasaki City collected A-bomb accounts from citizens who were not in the designated A-bombed area, although they were within a radius of 12 kilometers from the hypocenter. Many citizens provided testimonies, which included such descriptions as witnessing black ash and dust falling to the ground.

In 2002, the national government established a new category—“a person with A-bombing experience”—unique to Nagasaki to define such people. If people who fall under this new category are recognized to suffer from mental illness or other specific diseases such as hypertension due to their A-bombing experience, they are eligible to receive government support including compensation of medical expenses to treat such disease. Nevertheless, a big gap exists in aid between hibakusha and such people with A-bombing experience. As of the end of March 2019, those who belonged to this special category numbered 5,932 individuals. Ms. Iwanaga was diagnosed as having thyroid abnormalities in her 50’s. She now suffers from ringing of the ears and is frequently in and out of the hospital. She is not convinced by her status “a person with A-bombing experience.”

Seeking equal treatment, this group of people filed a lawsuit against the government, but Japan’s Supreme Court rejected the appeal by 387 plaintiffs in December 2017. The court accepted the argument made by the government, ruling it was hard to claim that the plaintiffs suffered from immediate health damage unless they were within a five-kilometer radius from the hypocenter. A total of 28 plaintiffs, including Ms. Iwanaga, who had served as chief secretary of the plaintiffs, filed another lawsuit in Nagasaki district court. Some of the plaintiffs who lost the case at the Supreme Court level, however, have already died.

During the court trial period, with a belief that expansion of the A-bombed area would be necessary, the Nagasaki City established a research group consisting of experts in 2013, with the aim of gaining “scientific and reasonable evidence” demanded by the Japanese government for expansion of the A-bombed area. Since 2015, the city has resumed its demand that the national government expand the A-bombed area.

In Hiroshima, the biggest focus is likely the claim about health damage due to “black rain,” which included dust and soot containing radioactive materials.

An ascending air current resulted from the extensive fires in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, which led to rainfall over a wide area. According to an investigation conducted by engineers from the Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory (now Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory) during August—December 1945, it was believed that heavy rain had fallen in an oval-shaped area stretching northwest from around the hypocenter 19 kilometers in length by about 11 kilometers in width.

In 1976, the Japanese national government set up a new system in which those who had been exposed to the rain in this “heavy rain area” could undergo health examinations at the expense of the national government and obtain an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate, provided they were diagnosed with diseases recognized by the government, such as cancer or cataracts.

An oval-shaped area lying outside the heavy rain area is termed the “light rain area.” Those who were in that area are not included as part of the scope of provision of relief. However, some residents in the light rain area or further outside that zone argue that their health conditions were certainly exacerbated by the rainfall they experienced.

Chika Maeda, 78, a resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima, who was born and raised in Minochi-mura (now part of Yuki-cho in Saeki Ward), located about 20 kilometers north of the hypocenter, still remembers the scene she witnessed 75 years ago in her home, which stood along Ota River. After the sky shone brightly, she went out to the garden and saw burned bits of paper falling from the sky. She has no further memory from that moment on but was later told she also had been exposed to rain in fields outside.

The area on the other side of the river from where she lived is designated a heavy rain area. Ms. Maeda’s sister, who is four years older, obtained a certificate because she was playing in in the heavy rain area on the other side of the river at the time of the bombing. Ms. Maeda said, “It’s not fair that I am not eligible for the certificate just because I was on this side of the river.” Five years ago, she was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. She also developed cataracts. Her deceased mother suffered from skin and heart disease. In 1978, her father formed a citizens’ council, which turned into the current Hiroshima Prefecture Atomic Bomb Black Rain Council.

In contrast to the boundary designated by the national government, Yoshinobu Masuda, the former laboratory chief at the Meteorological Agency's Meteorological Research Institute, provided a report in 1988 concluding that the rainfall area was about four times larger than the one identified by an investigation carried out in 1945. Both Hiroshima City and Hiroshima Prefecture requested that the national government broaden the heavy rain area by six times more than the current area, based on survey results they put together in 2010. However, their request has yet to be realized.

In 2015, Ms. Maeda and a number of residents who live in Hiroshima City and the town of Akiota-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture, filed a group lawsuit against the prefecture and city governments, which had rejected their application for A-bomb Survivor’s Certificates. They claimed that they were affected by internal exposure, a condition in which radioactive particles are absorbed internally even though they were not directly exposed to the atomic bomb’s thermal rays, blast, or radiation. The plaintiffs in the lawsuit are seeking to have the area eligible for provision of relief be expanded.

Of the 85 plaintiffs, 12 have already died, including Masayuki Matsumoto, who served as deputy chief of the plaintiff group. The district court’s decision will be made in July. A judicial judgment on the black rain issue will be given for the first time.

Rather than the prefecture and the city governments, which are the defendants in the lawsuit, the plaintiffs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki have questioned the responsibility of the national government, which they claim underestimated damage wrought by the atomic bombings. One of the obstacles they face in common is the report provided by the then Health and Welfare Minister’s private advisory body in 1980, which concluded that the designation of A-bombed areas should be limited to cases in which there is scientific and reasonable evidence. This idea has defined the national government’s guidelines for its policy of providing aid to A-bomb survivors.

Regarding the definition of the black rain area in Hiroshima, Yoshinobu Masuda, 96 years old now, said angrily, “The rainfall area cannot have been a perfect oblong shape. I think my research result would be more scientific. It’s distressing.” Masao Tomonaga, 76, an honorary director of the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital, pointed out, “If the national government prioritizes science, it means the wrong decision was made by the government when it designated the A-bombed area in Nagasaki in accordance with local administrative districts.” He added, “The only option that remains is a political settlement.”

(Originally published on May 25, 2020)

Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificates are issued to people who directly experienced the atomic bombing within designated areas, those exposed to residual radiation after entering the city center within two weeks of the bombings, and those exposed to radiation while administering aid to others. However, people who experienced the atomic bombing not falling under those categories have continued their appeal for recognition as hibakusha (A-bomb survivors). In Nagasaki, boundaries were drawn to determine eligibility for aid as A-bomb survivors in accordance with governmental administrative districts. Meanwhile, in Hiroshima, “black rain” is said to have fallen broadly. By focusing on issues specific to each city, the two newspapers herein shed light on the current conditions surrounding these issues in the two A-bombed cities.

Nagasaki differentiates A-bomb survivors depending on administrative district at time of bombing—despite same distance from hypocenter

Chiyoko Iwanaga, 84, a former elementary school teacher living in Nagasaki City, gave an explanation with hand outstretched. The area in front of the wall near where she stood is a neighborhood known as Sueishi-machi, and on the other side of the wall is Fukahori-machi. At that time, 75 years ago, Sueishi-machi was part of Nagasaki City, and Fukahori-machi was a village.

On August 9, 1945, when she was nine years old, Ms. Iwanaga was overwhelmed by the flash and blast of the atomic bombing. One week later, she bled from her gums and had pain and a feeling of pressure in her throat. At the time of the bombing, she was in the former village of Fukahori-mura. Unlike people who were in the neighborhood of Sueishi-machi, which was located within the Nagasaki city limits, she has not been officially recognized as a hibakusha. “Why haven’t I been designated even though I was the same distance from the hypocenter as other A-bomb survivors,” she said.

In Nagasaki, whether someone is hibakusha has generally been determined by the administrative district where he or she was at the time of the bombing. The so-called “A-bombed area” in Nagasaki is an uneven oval shape stretching 24.9 kilometers north and south and 13.9 kilometers east and west. The area was expanded in 1974 and 1976, including one part for which people in the area at the time of the bombing could obtain an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate after undergoing a health examination at national government expense, similar to the survivors in Hiroshima who were in “heavy rain areas.”

About a half century after the atomic bombing, Nagasaki City collected A-bomb accounts from citizens who were not in the designated A-bombed area, although they were within a radius of 12 kilometers from the hypocenter. Many citizens provided testimonies, which included such descriptions as witnessing black ash and dust falling to the ground.

In 2002, the national government established a new category—“a person with A-bombing experience”—unique to Nagasaki to define such people. If people who fall under this new category are recognized to suffer from mental illness or other specific diseases such as hypertension due to their A-bombing experience, they are eligible to receive government support including compensation of medical expenses to treat such disease. Nevertheless, a big gap exists in aid between hibakusha and such people with A-bombing experience. As of the end of March 2019, those who belonged to this special category numbered 5,932 individuals. Ms. Iwanaga was diagnosed as having thyroid abnormalities in her 50’s. She now suffers from ringing of the ears and is frequently in and out of the hospital. She is not convinced by her status “a person with A-bombing experience.”

Seeking equal treatment, this group of people filed a lawsuit against the government, but Japan’s Supreme Court rejected the appeal by 387 plaintiffs in December 2017. The court accepted the argument made by the government, ruling it was hard to claim that the plaintiffs suffered from immediate health damage unless they were within a five-kilometer radius from the hypocenter. A total of 28 plaintiffs, including Ms. Iwanaga, who had served as chief secretary of the plaintiffs, filed another lawsuit in Nagasaki district court. Some of the plaintiffs who lost the case at the Supreme Court level, however, have already died.

During the court trial period, with a belief that expansion of the A-bombed area would be necessary, the Nagasaki City established a research group consisting of experts in 2013, with the aim of gaining “scientific and reasonable evidence” demanded by the Japanese government for expansion of the A-bombed area. Since 2015, the city has resumed its demand that the national government expand the A-bombed area.

Hiroshima’s focus: to what extent did the “black rain” fall—Only separated by a river

In Hiroshima, the biggest focus is likely the claim about health damage due to “black rain,” which included dust and soot containing radioactive materials.

An ascending air current resulted from the extensive fires in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, which led to rainfall over a wide area. According to an investigation conducted by engineers from the Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory (now Hiroshima Local Meteorological Observatory) during August—December 1945, it was believed that heavy rain had fallen in an oval-shaped area stretching northwest from around the hypocenter 19 kilometers in length by about 11 kilometers in width.

In 1976, the Japanese national government set up a new system in which those who had been exposed to the rain in this “heavy rain area” could undergo health examinations at the expense of the national government and obtain an A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate, provided they were diagnosed with diseases recognized by the government, such as cancer or cataracts.

An oval-shaped area lying outside the heavy rain area is termed the “light rain area.” Those who were in that area are not included as part of the scope of provision of relief. However, some residents in the light rain area or further outside that zone argue that their health conditions were certainly exacerbated by the rainfall they experienced.

Chika Maeda, 78, a resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima, who was born and raised in Minochi-mura (now part of Yuki-cho in Saeki Ward), located about 20 kilometers north of the hypocenter, still remembers the scene she witnessed 75 years ago in her home, which stood along Ota River. After the sky shone brightly, she went out to the garden and saw burned bits of paper falling from the sky. She has no further memory from that moment on but was later told she also had been exposed to rain in fields outside.

The area on the other side of the river from where she lived is designated a heavy rain area. Ms. Maeda’s sister, who is four years older, obtained a certificate because she was playing in in the heavy rain area on the other side of the river at the time of the bombing. Ms. Maeda said, “It’s not fair that I am not eligible for the certificate just because I was on this side of the river.” Five years ago, she was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. She also developed cataracts. Her deceased mother suffered from skin and heart disease. In 1978, her father formed a citizens’ council, which turned into the current Hiroshima Prefecture Atomic Bomb Black Rain Council.

In contrast to the boundary designated by the national government, Yoshinobu Masuda, the former laboratory chief at the Meteorological Agency's Meteorological Research Institute, provided a report in 1988 concluding that the rainfall area was about four times larger than the one identified by an investigation carried out in 1945. Both Hiroshima City and Hiroshima Prefecture requested that the national government broaden the heavy rain area by six times more than the current area, based on survey results they put together in 2010. However, their request has yet to be realized.

In 2015, Ms. Maeda and a number of residents who live in Hiroshima City and the town of Akiota-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture, filed a group lawsuit against the prefecture and city governments, which had rejected their application for A-bomb Survivor’s Certificates. They claimed that they were affected by internal exposure, a condition in which radioactive particles are absorbed internally even though they were not directly exposed to the atomic bomb’s thermal rays, blast, or radiation. The plaintiffs in the lawsuit are seeking to have the area eligible for provision of relief be expanded.

Of the 85 plaintiffs, 12 have already died, including Masayuki Matsumoto, who served as deputy chief of the plaintiff group. The district court’s decision will be made in July. A judicial judgment on the black rain issue will be given for the first time.

Japanese government’s demand for scientific evidence is inconsistent

Rather than the prefecture and the city governments, which are the defendants in the lawsuit, the plaintiffs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki have questioned the responsibility of the national government, which they claim underestimated damage wrought by the atomic bombings. One of the obstacles they face in common is the report provided by the then Health and Welfare Minister’s private advisory body in 1980, which concluded that the designation of A-bombed areas should be limited to cases in which there is scientific and reasonable evidence. This idea has defined the national government’s guidelines for its policy of providing aid to A-bomb survivors.

Regarding the definition of the black rain area in Hiroshima, Yoshinobu Masuda, 96 years old now, said angrily, “The rainfall area cannot have been a perfect oblong shape. I think my research result would be more scientific. It’s distressing.” Masao Tomonaga, 76, an honorary director of the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital, pointed out, “If the national government prioritizes science, it means the wrong decision was made by the government when it designated the A-bombed area in Nagasaki in accordance with local administrative districts.” He added, “The only option that remains is a political settlement.”

(Originally published on May 25, 2020)