Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Dispersed materials, Part 8: Significance of original work

Apr. 17, 2020

Teachers opposed student mobilization for outdoor work

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Original writings and recordings are vivid reminders

The Hiroshima Prefectural Archives, located in the city’s Naka Ward, has in its possession original accounts of the atomic bombing written 45 years ago by 422 individuals, including employees of the prefectural government and bereaved family members. The original wooden building, located about 900 meters from the hypocenter, was completely destroyed in the bombing. A total of 1,141 employees died and many of the materials were consumed by fire. All the more because of this, the accounts are valuable records by which can be discerned the nature of the prefectural government before the atomic bombing.

Accounts written by 122 people were published as the Hiroshima Kencho Genbaku Hisaishi (Chronicle of A-bomb Damage to the Hiroshima Prefectural Government Offices) in 1976. In Hiroshima, about 7,200 students who had been mobilized for the war effort perished in the atomic bombing. Eighty percent of the students had been mobilized to help tear down homes to create fire lanes. What circumstances led to that result? How were “decent opinions” frankly expressed during the war ignored? Although the publication is partly comprised of excerpts, the chronicle provides a glimpse into what actually happened.

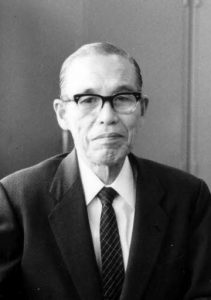

Takeshi Hasegawa (who died at age 90 in 1993) worked for the prefectural government’s department of military affairs, in which was located the headquarters of the wartime student mobilization efforts. In early July 1945, Mr. Hasegawa attended discussions among representatives of the military, the prefectural government, municipal government, and each of the schools in the district. The representatives discussed work to forcibly tear down private homes in the center of the city to create fire lanes.

In the city of Hiroshima, the mobilization work began in accordance with a Home Ministry notification in November 1944. Would first- and second-year junior high school students really be mobilized? It was a time when a sense of crisis over U.S. air raids was growing. School officials opposed the order, citing the difficulty of evacuation. Mr. Hasegawa wrote, “While hitting the floor with a saber, an Imperial Japanese Army officer forced a prefectural internal affairs manager to make the decision, saying it would be natural for young students to be mobilized to implement the strategy.”

Some parts of accounts were omitted

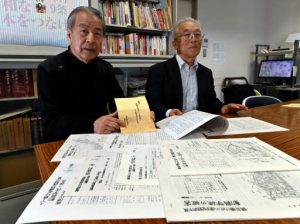

The Tatemono Sokai Doin Gakuto no Genbaku Hisai wo Kirokusuru Kai (a group working to make known the fact that students were mobilized to tear down homes and were victims in the atomic bombing) is composed of former teachers. Hideyuki Sato, 75, a group member and resident of Minami Ward, said, “We now fully understand the teachers’ concerns behind the scenes of the tragedy as well as the military’s heavy-handed attitude.”

Mr. Sato and other members discovered Mr. Hasegawa’s original account in a special exhibit held at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 2004. In the same year, they created a booklet, conveying the back story of children being mobilized from classrooms, titled Dokoku no Higeki wa Naze Okottanoka (Why Did the Lamentable Tragedy Happen?), in which the group published the parts of the account that had been exhibited.

Sections omitted from the chronicle published in 1976 were vividly described in the original account. School officials unanimously had said that mobilizing students was dangerous and opposed it with everything they had. The man who had tapped the floor with his saber was described as Lieutenant General “So and so.” The group investigated and found that he was likely a commanding officer of the Chugoku Military District Headquarters. The prefectural internal affairs manager had pondered the issue deeply but ultimately was forced into the decision to mobilize students. In the end, both individuals were killed in the atomic bombing.

Making index of all writers

Reporters at the Chugoku Shimbun read the full text of the original account with consent from the family of the late Mr. Hasegawa. In the account, he expressed regret. “In today’s judgment, it would have been right to refuse to mobilize students, and we should have protected them.” This is the lesson that Mr. Hasegawa, who was the principal of an elementary school prior to the war and a university employee after, wanted to pass on to the next generation. Some facts can only be discerned by gathering primary documents, the originals.

With the passing years, it is becoming more and more difficult to access the A-bomb accounts of those who were already adults 75 years ago. The Hiroshima Prefectural Archives plans to begin making an index of all the writers of such accounts, including 300 people whose stories did not appear in the prefectural chronicle of A-bomb accounts.

Shunichiro Arai, 88, a resident of Minami Ward, experienced the atomic bombing when he was a first-year student at the middle school affiliated with the Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now the junior high school affiliated with Hiroshima University). In 1981, he invited nine of his former teachers to hold discussions, which he recorded by cassette tape in a five-hour original sound source. In January 2020, he transferred the old cassette tape recording to CDs.

Mr. Arai and other first-year students from his junior high school were mobilized to help with agricultural work in the village of Hara (now the city of Higashihiroshima) some distance from the city of Hiroshima. “Students in lower grades were mobilized under the pretext of increasing food production,” he wrote. “Thanks to the fact that it was a national school, we were able to have a slightly different attitude about orders from the prefectural government.” The late Chikara Miyaoka, one of the teachers who searched for homes that would take in the mobilized students, explained calmly how they took pains to make the mobilization seem as if it were an actual evacuation. Naturally, they also were wary of air raids.

An outline of the discussions appeared in the Showa Nijunen no Kiroku (A Record of 1945), which Mr. Arai and his classmates published in 1984. Mr. Arai wrote, “Thanks to our teachers’ excellent decisions and struggles, some students were able to survive. I want future generations to take away this message throughout the entire book.” He plans on sending the CDs produced by the group to the alumni associations of his alma mater school.

(Originally published on April 17, 2020)