Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Recreating cityscapes in former Nakajima district, surroundings, Part 1: Nakajima Honmachi

Mar. 9, 2020

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

The former Nakajima district, situated in the river delta area between the Motoyasu and Honkawa rivers, was once packed with shops and houses. On August 6, 1945, in the closing days of World War II, the U.S. military dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, targeting the Aioi Bridge on the north side of the district. The area was reduced to ashes due to its location directly underneath the explosion. After the end of World War II, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (currently part of Naka Ward), now a green zone, was built on the site. This article will trace with photographs Nakajima Honmachi, a district that had bustled with crowds of people until that day.

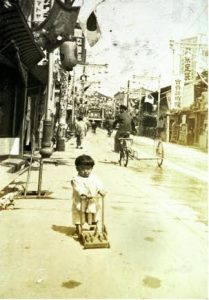

“That’s my house. I’m surprised it looks so old,” said Midori Takamatsu, 86, a resident of Minami Ward. She picked up the black-and-white photo and smiled nostalgically. The photo captured kimono-clad women and a male school student walking along Nakajima Hondori shopping street. A part of a shop signboard reading “Kamoji and Cosmetics” can also be seen in the photo. The building with the sign included a shop called Hatsukaichiya, which was managed by Shinichi Kihara, Ms. Takamatsu’s father. It was also the home where she was born.

The photo she looked at was donated to the Hiroshima Municipal Archives in 2014 by the bereaved family of the manager of Star Photo Studio, which once stood near the present-day Cenotaph for the A-bomb victims. It was the first time in 75 years that Ms. Takamatsu, who had lost everything in the fires after the atomic bombing, saw the appearance of her house before the atomic bombing.

Hatsukaichiya was just two doors down from the Taishoya Kimono Shop (now known as the Rest House) to the west. Ms. Takamatsu used to swim in the Motoyasu River after school and enjoyed playing house on the bank opposite the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-bomb Dome).

In April 1945, Ms. Takamatsu, then a sixth-year student at Nakajima National School, was evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima prefecture apart from her family. Soon after, the Kihara family moved to the area near Jisenji Temple, which is now on the north side of the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, because their original house had been demolished to create a vacant lot to serve as an evacuation site in case of fire during air raids.

The atomic bomb was dropped on August 6. Ms. Takamatsu’s older sister and brother were safe, as they had left home and moved to the place where they were mobilized to work. But her parents and two young brothers died in the atomic bombing. She had heard from her older sister that there had been human remains appearing to be those of her father Shinichi, 48 at the time, and mother Masako, 42, in the remains of their home. Both of her younger brothers, Hiroshi, 4, and Minoru, 1, remain missing.

For a long time, she did not go to Peace Memorial Park and did not dare to talk about the atomic bombing. Nevertheless, her feelings began to change about 20 years ago. Through interactions with former district residents, she also became interested in measures to effectively preserve and utilize the Rest House building. “To preserve the only A-bombed building remaining in the park is to show other people proof that my deceased family used to live in the current park area,” said Ms. Takamatsu. “I don’t want people to have the misunderstanding that this area was always a park.”

Renovation work is now underway at the Rest House. Plans call for it to reopen in July, prior to the milestone 75th A-bombing anniversary, along with an exhibit space to convey information about the former Nakajima district.

The Taishoya Kimono Shop was closed in 1943 because of the fabric-control law enacted during the war. At the time of the atomic bombing, its building was being used as the Fuel Hall by the Hiroshima Prefectural Fuel Rationing Union. It was about 170 meters from the hypocenter. Of 37 workers who worked at the hall, eight managed to escape from the building. However, all of the workers, except for one person who survived miraculously, died soon thereafter.

One of the victims was Misako Hamai, then 22 and a relative of Tokuso Hamai, 85, a resident of Hatsukaichi. After she was exposed to the bombing in an underground space, she spent a night under the nearby Motoyasu Bridge. On the following day, Ms. Hamai fled to Miyauchi-mura (now part of Hatsukaichi), where Mr. Hamai had evacuated.

Afterwards, Misako stayed at the home of Mr. Hamai’s grandmother. Though she did not have visible wounds, she vomited a vast amount of blood on August 23. Mr. Hamai still cannot forget the final moments of the life of Misako, who waved her hand as she died.

Mr. Hamai, who grew up at the Hamai Barbershop, which was located in the neighborhood of Hatsukaichiya, is the sole survivor of the family, as four others were killed in the atomic bombing. Their remains have never been recovered. “Even now, I still feel my family might be hiding themselves somewhere,” said Mr. Hamai. Whenever he finds time, he pays a visit to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Ms. Takamatsu and Mr. Hamai have been communicating the memories they have of the former Nakajima Honmachi area to younger generations. They do so by sharing their experience at gatherings of the Hiroshima Fieldwork Execution Committee, a citizen’s group collecting testimonies from former residents about the district close to the hypocenter. “Our fathers and other family members lived life with heart and soul in this place,” they said. Their goal is to have tourists and students on field trips who come from Japan and overseas can understand the cityscape where they once lived.

(Originally published on March 9, 2020)

Peace Memorial Park was once an urban area

Former residents want evidence to remain that family victims lived in district before A-bombing

The former Nakajima district, situated in the river delta area between the Motoyasu and Honkawa rivers, was once packed with shops and houses. On August 6, 1945, in the closing days of World War II, the U.S. military dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, targeting the Aioi Bridge on the north side of the district. The area was reduced to ashes due to its location directly underneath the explosion. After the end of World War II, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (currently part of Naka Ward), now a green zone, was built on the site. This article will trace with photographs Nakajima Honmachi, a district that had bustled with crowds of people until that day.

“That’s my house. I’m surprised it looks so old,” said Midori Takamatsu, 86, a resident of Minami Ward. She picked up the black-and-white photo and smiled nostalgically. The photo captured kimono-clad women and a male school student walking along Nakajima Hondori shopping street. A part of a shop signboard reading “Kamoji and Cosmetics” can also be seen in the photo. The building with the sign included a shop called Hatsukaichiya, which was managed by Shinichi Kihara, Ms. Takamatsu’s father. It was also the home where she was born.

The photo she looked at was donated to the Hiroshima Municipal Archives in 2014 by the bereaved family of the manager of Star Photo Studio, which once stood near the present-day Cenotaph for the A-bomb victims. It was the first time in 75 years that Ms. Takamatsu, who had lost everything in the fires after the atomic bombing, saw the appearance of her house before the atomic bombing.

Hatsukaichiya was just two doors down from the Taishoya Kimono Shop (now known as the Rest House) to the west. Ms. Takamatsu used to swim in the Motoyasu River after school and enjoyed playing house on the bank opposite the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-bomb Dome).

In April 1945, Ms. Takamatsu, then a sixth-year student at Nakajima National School, was evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima prefecture apart from her family. Soon after, the Kihara family moved to the area near Jisenji Temple, which is now on the north side of the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, because their original house had been demolished to create a vacant lot to serve as an evacuation site in case of fire during air raids.

The atomic bomb was dropped on August 6. Ms. Takamatsu’s older sister and brother were safe, as they had left home and moved to the place where they were mobilized to work. But her parents and two young brothers died in the atomic bombing. She had heard from her older sister that there had been human remains appearing to be those of her father Shinichi, 48 at the time, and mother Masako, 42, in the remains of their home. Both of her younger brothers, Hiroshi, 4, and Minoru, 1, remain missing.

For a long time, she did not go to Peace Memorial Park and did not dare to talk about the atomic bombing. Nevertheless, her feelings began to change about 20 years ago. Through interactions with former district residents, she also became interested in measures to effectively preserve and utilize the Rest House building. “To preserve the only A-bombed building remaining in the park is to show other people proof that my deceased family used to live in the current park area,” said Ms. Takamatsu. “I don’t want people to have the misunderstanding that this area was always a park.”

Renovation work is now underway at the Rest House. Plans call for it to reopen in July, prior to the milestone 75th A-bombing anniversary, along with an exhibit space to convey information about the former Nakajima district.

The Taishoya Kimono Shop was closed in 1943 because of the fabric-control law enacted during the war. At the time of the atomic bombing, its building was being used as the Fuel Hall by the Hiroshima Prefectural Fuel Rationing Union. It was about 170 meters from the hypocenter. Of 37 workers who worked at the hall, eight managed to escape from the building. However, all of the workers, except for one person who survived miraculously, died soon thereafter.

One of the victims was Misako Hamai, then 22 and a relative of Tokuso Hamai, 85, a resident of Hatsukaichi. After she was exposed to the bombing in an underground space, she spent a night under the nearby Motoyasu Bridge. On the following day, Ms. Hamai fled to Miyauchi-mura (now part of Hatsukaichi), where Mr. Hamai had evacuated.

Afterwards, Misako stayed at the home of Mr. Hamai’s grandmother. Though she did not have visible wounds, she vomited a vast amount of blood on August 23. Mr. Hamai still cannot forget the final moments of the life of Misako, who waved her hand as she died.

Mr. Hamai, who grew up at the Hamai Barbershop, which was located in the neighborhood of Hatsukaichiya, is the sole survivor of the family, as four others were killed in the atomic bombing. Their remains have never been recovered. “Even now, I still feel my family might be hiding themselves somewhere,” said Mr. Hamai. Whenever he finds time, he pays a visit to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

Ms. Takamatsu and Mr. Hamai have been communicating the memories they have of the former Nakajima Honmachi area to younger generations. They do so by sharing their experience at gatherings of the Hiroshima Fieldwork Execution Committee, a citizen’s group collecting testimonies from former residents about the district close to the hypocenter. “Our fathers and other family members lived life with heart and soul in this place,” they said. Their goal is to have tourists and students on field trips who come from Japan and overseas can understand the cityscape where they once lived.

(Originally published on March 9, 2020)