Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Mobilized Students 5

Jul. 6, 2015

Experienced A-bombing after night shift in semi-underground shelter

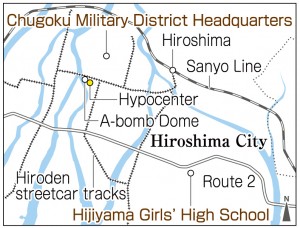

A concrete semi-underground shelter still exists on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle. It served as the operations room of the air defense efforts pursued by the Chugoku Military District Headquarters, which was located on the castle grounds. The shelter, which is also an A-bombed structure, is enclosed by a fence and managed by the Hiroshima municipal government.

Tsuyako Hanada (née Morita), 84, a resident of Asakita Ward, went inside the shelter this summer for the first time in 70 years. “It feels like it happened just yesterday,” she murmured and covered her mouth with her hands. She could not hold back her tears.

The shelter is about 790 meters from the hypocenter. She was inside when the atomic bomb exploded on August 6, 1945.

Ms. Hanada was a third-year student at Hijiyama Girls’ High School and had been mobilized to assist at the headquarters building along with about 90 schoolmates. Their tasks involved transmitting air raid warnings after they were issued and alerts to each air defense surveillance site in the Chugoku region. Telecommunications equipment, including telephones, was installed in the shelter, and the students worked in three shifts around the clock.

Ms. Hanada said that she had been working the second shift. She was busy communicating information on air raid attacks by enemy planes, which continued intermittently from the night before, and greeted the morning of August 6 with little sleep. But the students on the third shift did not come on time to replace her shift. When she took off the headphone from her left ear while at the desk by a west-side window, then turned her head away, she felt a flash of light. When she came to, she realized that she had been blown across the room, along with the equipment.

She managed to struggle out and found the schoolmates who had come to replace her shift. Their skin was hanging from their bodies in tatters. She heard someone say, “Don’t worry about me. Just run away.” Many soldiers were covered in blood and writhing in agony. She followed some soldiers who could still walk and left the castle grounds. She saw people whose bellies had been torn open and dead horses.

Field hospital set up on castle grounds

Ms. Hanada followed droves of people on foot, thinking the scenes she saw were from another world entirely, and fled to Gion-cho (now Asaminami Ward). The next morning she went back to the Chugoku Military District Headquarters and found that a field hospital, “like something from hell,” had been set up on the grounds of the castle. While she was applying ointment to the victims, as she was told, she came across a schoolmate lying on the ground and mumbling.

Ms. Hanada, who was 14 at the time, stayed at the shelter and provided aid to the victims. She herself was experiencing bloody stools. Her family had evacuated earlier to Niho-cho (now Minami Ward). She doesn’t recall when her father came to retrieve her, but she remembers hearing, while in Niho-cho, the emperor’s radio broadcast in which he announced the end of the war.

Though she agreed to this interview and visited the shelter, Ms. Hanada became reticent when it came to the schoolmate she found, who died before her eyes. With her permission, part of her account from the book Honoo No Nakani (In Flames) is quoted below. This book was compiled and published in 1969 by schoolmates who survived the atomic bombing.

“She told me, ‘I hate the United States, and I can’t do anything, but be sure to get revenge for me.’ I promised her that I would, saying ‘Definitely.’ This might have given her some relief, and she passed away. I wondered what she was thinking when she died alone without her father or mother.”

Ms. Hanada’s account ends with the schoolmate’s death and her thoughts as a mobilized student at the time.

After the war, she temporarily transferred to a girls’ high school in the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, but ultimately graduated from Hijiyama Girls’ High School. She went to work for Chugoku Haiden (now the Chugoku Electric Power Company) and got married in 1954.

A-bomb blast damaged her inner ear

Ms. Hanada said with a smile, “When I was a newlywed, I couldn’t catch what my husband was saying.” When the atomic bomb exploded, the blast damaged her inner ear and she lost the hearing in her left ear. Still, they had a daughter and she ran the household. She now lives with her husband and has two grandchildren.

Hijiyama Girls’ Junior and Senior High Schools, the successor to Hijiyama Girls’ High School, holds a memorial ceremony on August 6 each year in front of the monument which stands by the shelter. Though Ms. Hanada has been invited to attend the ceremony, she has not gone because “remembering those days is very difficult.”

Of the third-year students who were mobilized to work at the Chugoku Military District Headquarters, 67 were killed in the atomic bombing. Yoshie Oka (née Okura), 84, a resident of Naka Ward, has sought to hand down her experience of the atomic bombing to younger generations as an A-bomb survivor in the shelter, and said that only six or seven schoolmates who survived are still alive today.

(Originally published on July 6, 2015)