Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Peace Education Today

Jun. 9, 2015

by Masakazu Domen, Yumi Kanazaki and Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writers

Peace education in Hiroshima, which once focused on the damage done by the atomic bombing, has evolved over the past seven decades. The teachers of the generation that directly felt the horrors of the war and the bombing have retired, succeeded by younger generations of teachers. The hours allotted for peace studies in the school day were trimmed long ago. Despite such circumstances, younger generations are seeking to take up the A-bomb survivors’ wishes and convey their experiences in unique ways to others around the world. This article explores the efforts being made by today’s students and teachers so that the terrible lessons learned from World War II will not be forgotten.

The Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), which opened on April 27 at U.N. headquarters in New York, provides an important opportunity for A-bomb survivors and Hiroshima citizens to call on the member nations to pursue negotiations in good faith to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons. Among the citizens and survivors from various countries, students from the A-bombed cities have made their presence felt through their messages.

Along with university students from Nagasaki, eight students from Hiroshima high schools took part in the Youth Forum organized by Mayors for Peace. These students attend Hiroshima Jogakuin Senior High School and Shudo High School, both located in the city of Hiroshima, and Eishin Gakuen, a high school in the eastern part of the prefecture. After jointly holding a Peace Summit eight years ago, students at these schools, along with Okinawa Shogaku Junior & Senior High Schools in Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, launched a signature drive to gather support for nuclear abolition. They handed some 44,000 signatures that were collected over the past year to Virginia Gamba, the director of the Office for Disarmament Affairs and deputy to the high representative for disarmament affairs for the United Nations.

“We have listened directly to the survivors, and their accounts are etched into our memories. Those of us who were born and raised in Hiroshima Prefecture have a duty to continue conveying their messages,” said Tomohiko Sakamoto, 17, a third-year student at Eishin Gakuen, and Airi Sakuhara, 16, a first-year student at the same school. They quoted from the survivor’s accounts they had heard directly and appealed for the cycle of war and the terror of nuclear weapons to be brought to an end.

What enabled these high school students to face this international conference without feeling overwhelmed by the scale of its theme? The answer can be found in the activities of the high school’s human rights club, of which Airi is a member.

Among other things, this club has held meetings with former leprosy patients, conducted interviews with survivors of World War II air raids on the city of Fukuyama, and taken part in activities at the Holocaust Education Center in Fukuyama. The members of the club read newspaper articles together and exchange views. They also learn about the suffering that Japan inflicted on the people of other nations during the war.

Kazutoshi Nobu, 50, the vice principal of the school and the club’s advisor, said, “We aspire to help create a world where there is no killing and no human rights are violated. One of our challenges is the issue of nuclear arms.” Mr. Nobu believes that peace education in various forms and settings will broaden the students’ horizons and their appeals for nuclear abolition will come to have universality.

The human rights club and the student council led the signature drive for nuclear abolition, and the entire school lent support to the effort. Because all the students at the school have made steady efforts, two student representatives from the school were dispatched to the major conference in New York.

While the students were gathering signatures, some A-bomb survivors said with tears in their eyes, “Thank you for appealing for nuclear abolition for us.” One survivor acknowledged, “My parents and siblings were killed that day. This is the first time I’ve told anyone.” At the same time, some people responded bluntly, saying, “This campaign is pointless” or “Nuclear weapons won’t be abolished.”

Airi said with conviction that it’s important to continue your efforts, no matter how small they may seem. She feels that the signature drive is her way of helping to hand down the A-bomb experiences.

Japanese students exchange views with U.S., Russian students

An international conference called the Critical Issues Forum (CIF) was held at Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior & Senior High School from April 2 to 4. A total of 34 high school students from the United States, Russia, and Japan expressed their views, in English, on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons and their elimination.

More than 300 students and teachers from Hiroshima Jogakuin Senior High School lost their lives in the atomic bombing. By learning about this time on an ongoing basis, the students have developed a good knowledge of this history. They read aloud A-bomb accounts from the school’s former students and explained the inhumane nature of nuclear arms. Akari Takesato, 17, a third-year student, said that she wanted students from the United States and Russia “to view this as a problem that affects them directly” rather than just engaging in an exchange of words.

Nanako Shiba and Shiori Serada, both 17 and third-year students at Yasuda Girls High School, said, “Students from Hiroshima are able to sense the reality of what happened.” Through listening to the accounts of survivors on different occasions, the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons is impressed in their hearts.

The CIF was launched in 1998 by the Middlebury Institute of International Study in Monterey, California and has been held every year with a view to promoting education for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. This was the first time that the forum was held in Japan. Masako Toki, 49, a researcher at the institute, said, “If young people from Japan and other places come together in Hiroshima to gain a sense of reality of what occurred 70 years ago, and if they play active roles in the world, they can make a difference in discussions on nuclear issues.”

--------------------

Painting A-bomb scenes from survivors’ accounts

Motomachi High School, located in downtown Hiroshima, puts a strong emphasis on art education and offers a Creative Expression Course to students in its general education program. Some students in this course create paintings which depict the experiences of A-bomb survivors. To create these works of art, each student listens directly to a survivor’s story.

One painting shows the Senda-machi area in central Hiroshima at about 10:30 on the morning of August 6, 1945. It is as if the groans of the victims who have suffered severe burns from the A-bomb explosion can be heard in the scene. As Mitsuo Kodama, 82, gives guidance on how strong the fire in the background was at around that time, Kana Tsumura, 16, a second-year student, wields her paintbrush.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Mr. Kodama was at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School), 900 meters from the hypocenter. He fled toward the Senda-machi area. “Even if there had been photographers there at that time, the scene was so hideous that they couldn’t have taken photos. I’m very grateful that the scene is now captured in a picture,” said Mr. Kodama. With a grim look on her face, Kana said, “I still can’t fully imagine the scene, no matter how much he explains what it was like...”

At the request of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, Motomachi High School began this art project eight years ago. So far, fifty-six paintings have been made based on the accounts of 19 survivors and donated to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The pictures are used when survivors share their account, creating another cycle of peace education.

In order to produce these works of art, the students must digest detailed information about the extreme conditions in the aftermath of the bombing and the miserable toll on the survivors. Psychologically, it becomes a heavy burden to bear. In painful detail, Mr. Kodama told how he fled with a young man whose eyeball had popped from his face and was hanging down. The young man held the eyeball in his hand.

Kana said, “This is something no one would want to see, but in order to hand down this experience, we mustn’t turn our eyes away.” Her teacher, Kazunuki Hashimoto, 55, sees the students growing. “It’s remarkable to watch them start talking about peace in their own words,” he said.

Yasutsugu Ogura, 46, an associate professor at Rikkyo University in Tokyo, has been observing this project from his perspective as a sociologist. He has visited Motomachi High School many times and interviewed the students and survivors. “The students come to understand the survivors’ experiences not as abstract ideas but more deeply, at the level of personal feelings.”

Yasusuke Tagawa, 87, described his experience to Haruki Tanaka, 17. Haruki painted numerous victims rushing to the river bank near Taisho-bashi Bridge. The third-year student said, “As I painted each person, I started to really feel, for the first time, that people died and that the bombing was unforgivable.”

To depict a mother holding her badly burned baby in her arms, one student’s mother became the model for the image. “Not only listening to the survivors’ accounts, but conveying them to someone else enables the students to become more sympathetic and gain a deeper understanding,” said Mr. Ogura, pointing out how this contributes to passing down the first-hand experiences of the survivors.

--------------------

Yuji Egusa, 87, head of the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association, was committed to pursuing peace education as a junior high school teacher. Now he shares his account of the atomic bombing with local students and those on school trips. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Mr. Egusa on how he views peace education today, based on his many years of experience.

How do you see the situation involving peace education today, 70 years after the atomic bombing?

It has been about 20 years since the generation of teachers who can speak first-hand about the war retired. When I started teaching in 1948, some students had burn scars from the atomic bombing. But now we rarely see any scars of the war in schools or in our daily lives. This is precisely why peace education is now so important. But I have some misgivings about the current situation.

Could you give specific examples?

Data shows that, even in Hiroshima, more and more children are unable to give the correct date and time of the atomic bombing or the country that dropped the bomb. If they visit the Peace Memorial Park and fold paper cranes without knowing who detonated the bomb and when, and without grasping a clear picture of the event, they will just end up feeling sentimental. They won’t ask themselves why the bomb was dropped or what should be done to prevent atomic explosions in the future.

The starting point is teaching about what really happened. Peace education shouldn’t be about abstract moral issues, but I’m afraid this trend has grown stronger.

Why is this, do you think?

It depends on the school or region, but teachers seem daunted by the fear that they might be accused of having a political bias. In the case of Hiroshima Prefecture, this is largely due to the corrective guidance given by the Ministry of Education in 1998. But this seems to be a national trend.

Is it good if students understand the atomic bombing as if it were a natural disaster without knowing who detonated the bomb and when? As a teacher who actually experienced the bombing, I used to teach my students that the bombing was unforgivable, clearly distinguishing this from animosity. I believe this should still be our orientation.

I regret that our feelings that the bombing was unforgivable, which are based on our experiences, weren’t handed down to the next generation of teachers more effectively. With the late Akira Ishida and others, we established the predecessor to the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association in 1969. I started telling my account in the late 1970s. I just didn’t want to remember the bombing until that time, and there was nothing I could do about it.

What should be done to revitalize peace education?

If teachers rely on a manual because they have no direct experiences, they will be more afraid to deviate from that manual. The key is to pay careful attention to the history of the area and the school and their characteristics. It has been a long while since teachers who are survivors left their schools, but there are trees and buildings that survived the bombing, other remnants of the war, and undiscovered memoirs of the war and the atomic bombing.

If these materials are found, younger teachers will have fresh resources and can consider them clues for their peace studies. These materials should feel even fresher to children. Under the current circumstances, there is a compelling need for a revival of peace education.

Profile

Yuji Egusa

Born in Fukuyama in 1927, Mr. Egusa was exposed to the atomic bombing on Kanawajima Island, where he worked as a mobilized student. He took part in the rescue operations in the city. After graduating from Hiroshima Normal School in 1948, he became a music teacher at Midorimachi Junior High School. He also taught at Noboricho Junior High School and Danbara Junior High School before retiring in 1988 at Midorimachi Junior High School. He has been the head of the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association since 2014. He is also a researcher at the Hiroshima Institute for Peace Education.

In May, the season of new green leaves, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is perpetually crowded with students on school trips and peace study field trips. During the past 10 years, around 300,000 students, from elementary school through high school, have visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum annually on such trips. In the peak seasons of May and October, students from about 1,000 schools visit the museum each month.

“It’s evident that peace education has become widespread and taken root. But even in Hiroshima, it’s very hard to deepen this learning,” said Hisaharu Matsui, 61, a former junior high school teacher. For more than 10 years, until he retired in the spring of 2014, he served as the head of the peace education section of an autonomous group of teachers pursuing educational research. Currently, he works as a learning support assistant at Ozu Junior High School, which is close to his home, and assists younger teachers, too.

“The parents of younger teachers and children were born after the end of the war. When the reality of the war and the atomic bombing has been lost, peace education requires considerable ingenuity,” he said.

Blank School Register

Mr. Matsui was a mathematics teacher. He started teaching at Midorimachi Junior High School in 1976. At that time the vice principal of the school was Sunao Tsuboi, now 90, chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo). At the beginning of his teaching career, Mr. Matsui and Mr. Tsuboi poured their efforts into peace education. With the student council, they made a booklet of accounts which described what happened to the students and teachers who lost their lives in the atomic bombing, when the school was officially known as Hiroshima Municipal Third National School. The booklet was made into a resource for peace education entitled Blank School Register.

After he was transferred to Kanon Junior High School, Mr. Matsui launched a project called “200,000 Faces,” in which students clipped people’s faces from newspapers and magazines and pasted them on a large sheet of paper. The purpose of the project was to have students realize the enormity of the number of victims. “We had teachers who were survivors, and I’m a second-generation survivor. The situation was the same for families of the students. Ideas for peace education came from things familiar to us,” Mr. Matsui said.

But the atomic bombing and war have come to “exist only in black-and-white films or in video games,” he said. The peace education section is now doing research to incorporate peace into the issues of bullying and poverty. “Their generation needs to have greater powers of imagination compared to our generation, and this is a difficult hurdle to overcome,” he said.

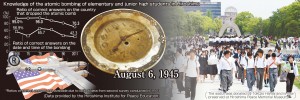

Students’ knowledge of Hiroshima declines

Is the standard of peace education in Hiroshima falling? One indicator is a survey that has been carried out on a regular basis by the Hiroshima Institute for Peace Education. In the seven surveys conducted between 1968 and 2011, students from the fifth grade of elementary school through the third year of junior high school were asked about the date and time of the atomic bombings, their experiences of listening to A-bomb survivors’ accounts, and related items.

The percentage of students who provided the correct date and time of the Hiroshima A-bombing was highest, at 65.7 percent, in the 1979 survey, the fourth one. In the 2011 survey, the result for this question was 42.3 percent. Concerning the country that dropped the bomb, 96.0 percent of the respondents answered correctly in 1979, but the percentage steadily declined to 70.3 in 2011.

The sources of information on the atomic bombing have also changed. In the first survey, more than 60 percent of students answered that they learned about the event from family members and relatives. But that percentage has dropped to 30 percent. Tairo Ito, 47, a professor at Hiroshima Kokusai Gakuin University, analyzed the results and wrote a research paper on them. “The results show that students don’t have many A-bomb survivors around them and that they have fewer opportunities to talk about the subject with their family members,” said Professor Ito. On the other hand, a higher percentage of students are listening to survivors’ accounts at school events. It appears that peace education at school is the only hope left.

In similar surveys conducted by the City of Hiroshima (the city’s education center or the board of education) every five years since 1995, the ratio of correct answers about the date and time of the bombing has been steadily declining. To stem this sinking result, the board of education introduced teaching materials entitled Hiroshima Peace Notes in fiscal 2013. These materials have been distributed to elementary schools, junior high schools, and high schools, and their use is encouraged in Japanese, social studies, and moral education classes.

“This material is of great help to younger teachers,” said Mr. Matsui. But he added, “If peace education becomes a program that simply follows a manual, this would be like putting the cart before the horse.” He emphasized the significance of schools creating their own materials for peace education.

Blank School Register, the booklet produced by Mr. Matsui and others, is still used as a teaching resource at Midorimachi Junior High School. In July, before the annual memorial ceremony held in August, members of the student council read out what happened to the victims through the school’s public address system, while all the other students read the same material. “Kazuko Fujinaga was exposed to the atomic bombing in the former Zakoba-cho area and died at her home in Motoujina...”

Blank School Register was compiled after members of the student council at that time visited victims’ families with a tape recorder and interviewed them. Takao Yokoyama, 46, is now in charge of peace education at the school. “The circumstances surrounding the deaths of 210 people were clarified, which required a huge amount of effort. This material makes us ask ourselves what we can do today,” Mr. Yokoyama said.

On the school grounds is a building that survived the atomic bombing and relatives of victims still attend the annual memorial ceremony. Mr. Yokoyama feels that efforts made with students could add new pages to this peace education material.

--------------------

Peace education is not another subject to “study”

“I’m sorry to tell you a sad story when you should be having fun on your school trip,” Chieko Kiriake, 85, said to about 40 students from Gunma Prefecture. The third-year junior high school students who had traveled to Hiroshima listened to Ms. Kiriake recount her experience of the atomic bombing. She told them that she had to help cremate schoolmates, one after another, on the grounds of Hiroshima Prefectural Second Girls Middle School, where she was a fourth-year student.

Encouraged by Tamotsu Eguchi, a junior high school teacher in Tokyo, Ms. Kiriake began sharing her account at the end of the 1970s. Mr. Eguchi, who died in 1998 at the age of 69, had made efforts to send students from Tokyo to Hiroshima on school trips. She told the students, who are about the same age as she was at the time of the bombing, “Live your lives to the fullest for those who couldn’t, though they wanted to live so badly.”

Conveying the survivors’ accounts of the atomic bombing is one of the key pillars of peace education. According to the figures given by some 20 Hiroshima-based groups that belong to an association of survivors committed to delivering their testimonies, the number of gatherings in which A-bomb survivors share their experiences has been on the rise since 1988, when they started keeping records. In the past 10 years, between 2,500 and 3,000 such sessions were held annually. The number of participants, many of them students on school trips, has never been below 200,000. Thus, the survivors’ testimonies have been contributing to peace education nationwide.

However, the student’s attitudes may have changed. Ms. Kiriake said, “When I began sharing my experience, sometimes the students cried along with me. In those days, it wasn’t unusual for the students to have lost family members to the war, and building sympathy wasn’t difficult.”

Hiroshi Shimizu, 72, the secretary general of Hiroshima Hidankyo, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi, tells students about his father, who was killed in the atomic bombing, and the miseries he went through after the war. “Students nowadays are well behaved, but they show no reaction and I sometimes feel uneasy, wondering whether they really get what I say.”

One junior high school teacher from Tokyo, making a school trip to Hiroshima, said, “This generation has no image of that time, so proper preparations must be made. Otherwise, they won’t be able to grasp the reality. But the emphasis at school is placed on academic subjects, and it’s hard to make time for such preparations.”

“It would be quite frustrating if the precious accounts shared by the survivors become just another form of ‘study,’” said Hideyuki Tokigawa, 42, a filmmaker. At the request of his old junior high school teacher, Mr. Tokigawa, a Hiroshima native, has been creating teaching materials which use the testimonies of A-bomb survivors. He has already filmed the accounts of two survivors, but “Recording their accounts isn’t enough,” he said. He hopes to take advantage of his experiences working for a U.S.-based TV channel specializing in documentaries and direct a film in Japan.

To Mr. Tokigawa, peace education was once something he had to “study,” and he felt reluctant. “Children these days must feel all the more reluctant,” he said. “It would make it worse if they were shown a film instead of listening directly to survivors.”

In order to attract their interest, Mr. Tokigawa is thinking of adding scenes where children follow in the postwar footsteps of survivors and relive their experiences. “For teaching materials to be put to good use, they must connect Hiroshima’s past and present,” said Mr. Tokigawa, his focus very clear.

Keywords

Hiroshima Peace Notes

These teaching materials have been distributed to all municipal elementary, junior high, and high schools in Hiroshima by the city’s board of education since fiscal 2013. They aim to have first- to third-graders appreciate the preciousness of life. This part includes Barefoot Gen, the manga story of a boy who survived the period of chaos after Hiroshima was devastated by the bomb. The theme for fourth- to sixth-graders is the reconstruction of the devastated city. Junior high school students learn about problems to be solved for peace in the world, and high school students study the role Hiroshima can play to help realize world peace.

(Originally published on May 23, 2015)

Peace education in Hiroshima, which once focused on the damage done by the atomic bombing, has evolved over the past seven decades. The teachers of the generation that directly felt the horrors of the war and the bombing have retired, succeeded by younger generations of teachers. The hours allotted for peace studies in the school day were trimmed long ago. Despite such circumstances, younger generations are seeking to take up the A-bomb survivors’ wishes and convey their experiences in unique ways to others around the world. This article explores the efforts being made by today’s students and teachers so that the terrible lessons learned from World War II will not be forgotten.

High school students take action on international stage

The Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), which opened on April 27 at U.N. headquarters in New York, provides an important opportunity for A-bomb survivors and Hiroshima citizens to call on the member nations to pursue negotiations in good faith to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons. Among the citizens and survivors from various countries, students from the A-bombed cities have made their presence felt through their messages.

Along with university students from Nagasaki, eight students from Hiroshima high schools took part in the Youth Forum organized by Mayors for Peace. These students attend Hiroshima Jogakuin Senior High School and Shudo High School, both located in the city of Hiroshima, and Eishin Gakuen, a high school in the eastern part of the prefecture. After jointly holding a Peace Summit eight years ago, students at these schools, along with Okinawa Shogaku Junior & Senior High Schools in Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, launched a signature drive to gather support for nuclear abolition. They handed some 44,000 signatures that were collected over the past year to Virginia Gamba, the director of the Office for Disarmament Affairs and deputy to the high representative for disarmament affairs for the United Nations.

“We have listened directly to the survivors, and their accounts are etched into our memories. Those of us who were born and raised in Hiroshima Prefecture have a duty to continue conveying their messages,” said Tomohiko Sakamoto, 17, a third-year student at Eishin Gakuen, and Airi Sakuhara, 16, a first-year student at the same school. They quoted from the survivor’s accounts they had heard directly and appealed for the cycle of war and the terror of nuclear weapons to be brought to an end.

What enabled these high school students to face this international conference without feeling overwhelmed by the scale of its theme? The answer can be found in the activities of the high school’s human rights club, of which Airi is a member.

Among other things, this club has held meetings with former leprosy patients, conducted interviews with survivors of World War II air raids on the city of Fukuyama, and taken part in activities at the Holocaust Education Center in Fukuyama. The members of the club read newspaper articles together and exchange views. They also learn about the suffering that Japan inflicted on the people of other nations during the war.

Kazutoshi Nobu, 50, the vice principal of the school and the club’s advisor, said, “We aspire to help create a world where there is no killing and no human rights are violated. One of our challenges is the issue of nuclear arms.” Mr. Nobu believes that peace education in various forms and settings will broaden the students’ horizons and their appeals for nuclear abolition will come to have universality.

The human rights club and the student council led the signature drive for nuclear abolition, and the entire school lent support to the effort. Because all the students at the school have made steady efforts, two student representatives from the school were dispatched to the major conference in New York.

While the students were gathering signatures, some A-bomb survivors said with tears in their eyes, “Thank you for appealing for nuclear abolition for us.” One survivor acknowledged, “My parents and siblings were killed that day. This is the first time I’ve told anyone.” At the same time, some people responded bluntly, saying, “This campaign is pointless” or “Nuclear weapons won’t be abolished.”

Airi said with conviction that it’s important to continue your efforts, no matter how small they may seem. She feels that the signature drive is her way of helping to hand down the A-bomb experiences.

Japanese students exchange views with U.S., Russian students

An international conference called the Critical Issues Forum (CIF) was held at Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior & Senior High School from April 2 to 4. A total of 34 high school students from the United States, Russia, and Japan expressed their views, in English, on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons and their elimination.

More than 300 students and teachers from Hiroshima Jogakuin Senior High School lost their lives in the atomic bombing. By learning about this time on an ongoing basis, the students have developed a good knowledge of this history. They read aloud A-bomb accounts from the school’s former students and explained the inhumane nature of nuclear arms. Akari Takesato, 17, a third-year student, said that she wanted students from the United States and Russia “to view this as a problem that affects them directly” rather than just engaging in an exchange of words.

Nanako Shiba and Shiori Serada, both 17 and third-year students at Yasuda Girls High School, said, “Students from Hiroshima are able to sense the reality of what happened.” Through listening to the accounts of survivors on different occasions, the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons is impressed in their hearts.

The CIF was launched in 1998 by the Middlebury Institute of International Study in Monterey, California and has been held every year with a view to promoting education for nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. This was the first time that the forum was held in Japan. Masako Toki, 49, a researcher at the institute, said, “If young people from Japan and other places come together in Hiroshima to gain a sense of reality of what occurred 70 years ago, and if they play active roles in the world, they can make a difference in discussions on nuclear issues.”

--------------------

Painting A-bomb scenes from survivors’ accounts

Motomachi High School, located in downtown Hiroshima, puts a strong emphasis on art education and offers a Creative Expression Course to students in its general education program. Some students in this course create paintings which depict the experiences of A-bomb survivors. To create these works of art, each student listens directly to a survivor’s story.

One painting shows the Senda-machi area in central Hiroshima at about 10:30 on the morning of August 6, 1945. It is as if the groans of the victims who have suffered severe burns from the A-bomb explosion can be heard in the scene. As Mitsuo Kodama, 82, gives guidance on how strong the fire in the background was at around that time, Kana Tsumura, 16, a second-year student, wields her paintbrush.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Mr. Kodama was at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School), 900 meters from the hypocenter. He fled toward the Senda-machi area. “Even if there had been photographers there at that time, the scene was so hideous that they couldn’t have taken photos. I’m very grateful that the scene is now captured in a picture,” said Mr. Kodama. With a grim look on her face, Kana said, “I still can’t fully imagine the scene, no matter how much he explains what it was like...”

At the request of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, Motomachi High School began this art project eight years ago. So far, fifty-six paintings have been made based on the accounts of 19 survivors and donated to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The pictures are used when survivors share their account, creating another cycle of peace education.

In order to produce these works of art, the students must digest detailed information about the extreme conditions in the aftermath of the bombing and the miserable toll on the survivors. Psychologically, it becomes a heavy burden to bear. In painful detail, Mr. Kodama told how he fled with a young man whose eyeball had popped from his face and was hanging down. The young man held the eyeball in his hand.

Kana said, “This is something no one would want to see, but in order to hand down this experience, we mustn’t turn our eyes away.” Her teacher, Kazunuki Hashimoto, 55, sees the students growing. “It’s remarkable to watch them start talking about peace in their own words,” he said.

Yasutsugu Ogura, 46, an associate professor at Rikkyo University in Tokyo, has been observing this project from his perspective as a sociologist. He has visited Motomachi High School many times and interviewed the students and survivors. “The students come to understand the survivors’ experiences not as abstract ideas but more deeply, at the level of personal feelings.”

Yasusuke Tagawa, 87, described his experience to Haruki Tanaka, 17. Haruki painted numerous victims rushing to the river bank near Taisho-bashi Bridge. The third-year student said, “As I painted each person, I started to really feel, for the first time, that people died and that the bombing was unforgivable.”

To depict a mother holding her badly burned baby in her arms, one student’s mother became the model for the image. “Not only listening to the survivors’ accounts, but conveying them to someone else enables the students to become more sympathetic and gain a deeper understanding,” said Mr. Ogura, pointing out how this contributes to passing down the first-hand experiences of the survivors.

--------------------

Interview with Yuji Egusa, head of the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association

Yuji Egusa, 87, head of the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association, was committed to pursuing peace education as a junior high school teacher. Now he shares his account of the atomic bombing with local students and those on school trips. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Mr. Egusa on how he views peace education today, based on his many years of experience.

How do you see the situation involving peace education today, 70 years after the atomic bombing?

It has been about 20 years since the generation of teachers who can speak first-hand about the war retired. When I started teaching in 1948, some students had burn scars from the atomic bombing. But now we rarely see any scars of the war in schools or in our daily lives. This is precisely why peace education is now so important. But I have some misgivings about the current situation.

Could you give specific examples?

Data shows that, even in Hiroshima, more and more children are unable to give the correct date and time of the atomic bombing or the country that dropped the bomb. If they visit the Peace Memorial Park and fold paper cranes without knowing who detonated the bomb and when, and without grasping a clear picture of the event, they will just end up feeling sentimental. They won’t ask themselves why the bomb was dropped or what should be done to prevent atomic explosions in the future.

The starting point is teaching about what really happened. Peace education shouldn’t be about abstract moral issues, but I’m afraid this trend has grown stronger.

Why is this, do you think?

It depends on the school or region, but teachers seem daunted by the fear that they might be accused of having a political bias. In the case of Hiroshima Prefecture, this is largely due to the corrective guidance given by the Ministry of Education in 1998. But this seems to be a national trend.

Is it good if students understand the atomic bombing as if it were a natural disaster without knowing who detonated the bomb and when? As a teacher who actually experienced the bombing, I used to teach my students that the bombing was unforgivable, clearly distinguishing this from animosity. I believe this should still be our orientation.

I regret that our feelings that the bombing was unforgivable, which are based on our experiences, weren’t handed down to the next generation of teachers more effectively. With the late Akira Ishida and others, we established the predecessor to the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association in 1969. I started telling my account in the late 1970s. I just didn’t want to remember the bombing until that time, and there was nothing I could do about it.

What should be done to revitalize peace education?

If teachers rely on a manual because they have no direct experiences, they will be more afraid to deviate from that manual. The key is to pay careful attention to the history of the area and the school and their characteristics. It has been a long while since teachers who are survivors left their schools, but there are trees and buildings that survived the bombing, other remnants of the war, and undiscovered memoirs of the war and the atomic bombing.

If these materials are found, younger teachers will have fresh resources and can consider them clues for their peace studies. These materials should feel even fresher to children. Under the current circumstances, there is a compelling need for a revival of peace education.

Profile

Yuji Egusa

Born in Fukuyama in 1927, Mr. Egusa was exposed to the atomic bombing on Kanawajima Island, where he worked as a mobilized student. He took part in the rescue operations in the city. After graduating from Hiroshima Normal School in 1948, he became a music teacher at Midorimachi Junior High School. He also taught at Noboricho Junior High School and Danbara Junior High School before retiring in 1988 at Midorimachi Junior High School. He has been the head of the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association since 2014. He is also a researcher at the Hiroshima Institute for Peace Education.

Sense of reality fades with change of generations

In May, the season of new green leaves, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is perpetually crowded with students on school trips and peace study field trips. During the past 10 years, around 300,000 students, from elementary school through high school, have visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum annually on such trips. In the peak seasons of May and October, students from about 1,000 schools visit the museum each month.

“It’s evident that peace education has become widespread and taken root. But even in Hiroshima, it’s very hard to deepen this learning,” said Hisaharu Matsui, 61, a former junior high school teacher. For more than 10 years, until he retired in the spring of 2014, he served as the head of the peace education section of an autonomous group of teachers pursuing educational research. Currently, he works as a learning support assistant at Ozu Junior High School, which is close to his home, and assists younger teachers, too.

“The parents of younger teachers and children were born after the end of the war. When the reality of the war and the atomic bombing has been lost, peace education requires considerable ingenuity,” he said.

Blank School Register

Mr. Matsui was a mathematics teacher. He started teaching at Midorimachi Junior High School in 1976. At that time the vice principal of the school was Sunao Tsuboi, now 90, chair of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hiroshima Hidankyo). At the beginning of his teaching career, Mr. Matsui and Mr. Tsuboi poured their efforts into peace education. With the student council, they made a booklet of accounts which described what happened to the students and teachers who lost their lives in the atomic bombing, when the school was officially known as Hiroshima Municipal Third National School. The booklet was made into a resource for peace education entitled Blank School Register.

After he was transferred to Kanon Junior High School, Mr. Matsui launched a project called “200,000 Faces,” in which students clipped people’s faces from newspapers and magazines and pasted them on a large sheet of paper. The purpose of the project was to have students realize the enormity of the number of victims. “We had teachers who were survivors, and I’m a second-generation survivor. The situation was the same for families of the students. Ideas for peace education came from things familiar to us,” Mr. Matsui said.

But the atomic bombing and war have come to “exist only in black-and-white films or in video games,” he said. The peace education section is now doing research to incorporate peace into the issues of bullying and poverty. “Their generation needs to have greater powers of imagination compared to our generation, and this is a difficult hurdle to overcome,” he said.

Students’ knowledge of Hiroshima declines

Is the standard of peace education in Hiroshima falling? One indicator is a survey that has been carried out on a regular basis by the Hiroshima Institute for Peace Education. In the seven surveys conducted between 1968 and 2011, students from the fifth grade of elementary school through the third year of junior high school were asked about the date and time of the atomic bombings, their experiences of listening to A-bomb survivors’ accounts, and related items.

The percentage of students who provided the correct date and time of the Hiroshima A-bombing was highest, at 65.7 percent, in the 1979 survey, the fourth one. In the 2011 survey, the result for this question was 42.3 percent. Concerning the country that dropped the bomb, 96.0 percent of the respondents answered correctly in 1979, but the percentage steadily declined to 70.3 in 2011.

The sources of information on the atomic bombing have also changed. In the first survey, more than 60 percent of students answered that they learned about the event from family members and relatives. But that percentage has dropped to 30 percent. Tairo Ito, 47, a professor at Hiroshima Kokusai Gakuin University, analyzed the results and wrote a research paper on them. “The results show that students don’t have many A-bomb survivors around them and that they have fewer opportunities to talk about the subject with their family members,” said Professor Ito. On the other hand, a higher percentage of students are listening to survivors’ accounts at school events. It appears that peace education at school is the only hope left.

In similar surveys conducted by the City of Hiroshima (the city’s education center or the board of education) every five years since 1995, the ratio of correct answers about the date and time of the bombing has been steadily declining. To stem this sinking result, the board of education introduced teaching materials entitled Hiroshima Peace Notes in fiscal 2013. These materials have been distributed to elementary schools, junior high schools, and high schools, and their use is encouraged in Japanese, social studies, and moral education classes.

“This material is of great help to younger teachers,” said Mr. Matsui. But he added, “If peace education becomes a program that simply follows a manual, this would be like putting the cart before the horse.” He emphasized the significance of schools creating their own materials for peace education.

Blank School Register, the booklet produced by Mr. Matsui and others, is still used as a teaching resource at Midorimachi Junior High School. In July, before the annual memorial ceremony held in August, members of the student council read out what happened to the victims through the school’s public address system, while all the other students read the same material. “Kazuko Fujinaga was exposed to the atomic bombing in the former Zakoba-cho area and died at her home in Motoujina...”

Blank School Register was compiled after members of the student council at that time visited victims’ families with a tape recorder and interviewed them. Takao Yokoyama, 46, is now in charge of peace education at the school. “The circumstances surrounding the deaths of 210 people were clarified, which required a huge amount of effort. This material makes us ask ourselves what we can do today,” Mr. Yokoyama said.

On the school grounds is a building that survived the atomic bombing and relatives of victims still attend the annual memorial ceremony. Mr. Yokoyama feels that efforts made with students could add new pages to this peace education material.

--------------------

Peace education is not another subject to “study”

“I’m sorry to tell you a sad story when you should be having fun on your school trip,” Chieko Kiriake, 85, said to about 40 students from Gunma Prefecture. The third-year junior high school students who had traveled to Hiroshima listened to Ms. Kiriake recount her experience of the atomic bombing. She told them that she had to help cremate schoolmates, one after another, on the grounds of Hiroshima Prefectural Second Girls Middle School, where she was a fourth-year student.

Encouraged by Tamotsu Eguchi, a junior high school teacher in Tokyo, Ms. Kiriake began sharing her account at the end of the 1970s. Mr. Eguchi, who died in 1998 at the age of 69, had made efforts to send students from Tokyo to Hiroshima on school trips. She told the students, who are about the same age as she was at the time of the bombing, “Live your lives to the fullest for those who couldn’t, though they wanted to live so badly.”

Conveying the survivors’ accounts of the atomic bombing is one of the key pillars of peace education. According to the figures given by some 20 Hiroshima-based groups that belong to an association of survivors committed to delivering their testimonies, the number of gatherings in which A-bomb survivors share their experiences has been on the rise since 1988, when they started keeping records. In the past 10 years, between 2,500 and 3,000 such sessions were held annually. The number of participants, many of them students on school trips, has never been below 200,000. Thus, the survivors’ testimonies have been contributing to peace education nationwide.

However, the student’s attitudes may have changed. Ms. Kiriake said, “When I began sharing my experience, sometimes the students cried along with me. In those days, it wasn’t unusual for the students to have lost family members to the war, and building sympathy wasn’t difficult.”

Hiroshi Shimizu, 72, the secretary general of Hiroshima Hidankyo, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi, tells students about his father, who was killed in the atomic bombing, and the miseries he went through after the war. “Students nowadays are well behaved, but they show no reaction and I sometimes feel uneasy, wondering whether they really get what I say.”

One junior high school teacher from Tokyo, making a school trip to Hiroshima, said, “This generation has no image of that time, so proper preparations must be made. Otherwise, they won’t be able to grasp the reality. But the emphasis at school is placed on academic subjects, and it’s hard to make time for such preparations.”

“It would be quite frustrating if the precious accounts shared by the survivors become just another form of ‘study,’” said Hideyuki Tokigawa, 42, a filmmaker. At the request of his old junior high school teacher, Mr. Tokigawa, a Hiroshima native, has been creating teaching materials which use the testimonies of A-bomb survivors. He has already filmed the accounts of two survivors, but “Recording their accounts isn’t enough,” he said. He hopes to take advantage of his experiences working for a U.S.-based TV channel specializing in documentaries and direct a film in Japan.

To Mr. Tokigawa, peace education was once something he had to “study,” and he felt reluctant. “Children these days must feel all the more reluctant,” he said. “It would make it worse if they were shown a film instead of listening directly to survivors.”

In order to attract their interest, Mr. Tokigawa is thinking of adding scenes where children follow in the postwar footsteps of survivors and relive their experiences. “For teaching materials to be put to good use, they must connect Hiroshima’s past and present,” said Mr. Tokigawa, his focus very clear.

Keywords

Hiroshima Peace Notes

These teaching materials have been distributed to all municipal elementary, junior high, and high schools in Hiroshima by the city’s board of education since fiscal 2013. They aim to have first- to third-graders appreciate the preciousness of life. This part includes Barefoot Gen, the manga story of a boy who survived the period of chaos after Hiroshima was devastated by the bomb. The theme for fourth- to sixth-graders is the reconstruction of the devastated city. Junior high school students learn about problems to be solved for peace in the world, and high school students study the role Hiroshima can play to help realize world peace.

(Originally published on May 23, 2015)