Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 11

Apr. 14, 2015

“The 65 Years I Have Lived Since the War” appears in print after nuclear accident in Fukushima

Akira Yamada, 88, a resident of Fukushima City in Fukushima Prefecture and a former president of Fukushima University, quickly conveyed his A-bomb experience after the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant of March 11, 2011. Made to endure another incident of radiation exposure, he felt compelled to write: “They ignored the warning.”

“I was shocked by the fact that the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, run by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) and shrouded by the safety myth for many years, was the site of a major accident, a “core meltdown” which resulted from the failure of the plant’s cooling system after the earthquake and tsunami. This was not “beyond the scope of assumptions,” the oft-repeated words of the Japanese government and TEPCO, since many experts foresaw just such a possibility. This was the outcome of having ignored their warnings.”

Mr. Yamada’s essay, entitled “Watashi no Ikita Sengo 65-nen” (“The 65 Years I Have Lived Since the War”) appeared in twelve installments from April 2011 to March 2012 in a newsletter published by the Association of the Fukushima Prefectural Health Insurance Doctors. About 1700 copies of each newsletter are printed. With a surge in requests to medical facilities for consultations involving the effects of radiation exposure, Mr. Yamada, who serves as the president of the Fukushima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, responded with assistance.

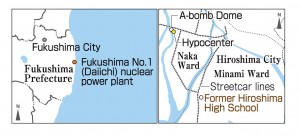

Mr. Yamada’s house is located about 60 kilometers northwest of the nuclear power station in Fukushima. He lives there with his wife. His yard, across from the Fukushima Prefectural Art Museum and Library, is covered with green plastic sheets which conceal the soil and grass that was removed after decontamination efforts in March by workers hired by the City of Fukushima.

Approximately 95,000 households throughout much of the city of Fukushima are the focus of decontamination efforts. The work proceeds slowly, though, due to difficulties in securing “temporary storage sites” where the radioactive waste collected by the city in each district can be placed. The green sheets, which are occasionally seen around the Moriai district, where Mr. Yamada’s house sits, reveal how grave the damage has been and how this damage persists today.

“Although I experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, I didn’t clearly recognize the danger of nuclear power plants and I had thought, even in the event of an emergency, the effects would never reach my house. I underestimated this,” said Mr. Yamada with a look of regret.

Mr. Yamada was a second-year student at the former Hiroshima High School (now Hiroshima University) when he experienced the atomic bombing. Prior to the bombing, he was a mobilized student at the naval arsenal in Kure, a city in Hiroshima Prefecture, and because of U.S. air raids there, he was forced to help deal with the dead, day after day. In despair, he returned home to the Midori-machi district (in today’s Minami Ward), located near the school, without informing school officials. This was one day before the Hiroshima attack on August 6, 1945.

Mr. Yamada was exposed to the atomic bomb while at his house, about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. He could do nothing but glance at a woman, apparently a fish peddler, with dazed disbelief as she fled with her flayed skin dangling down from her body. He himself developed symptoms of acute radiation sickness, including diarrhea.

After graduating from the faculty of economics at the University of Tokyo in 1951, he took a position at Fukushima University as a researcher of the history of the Japanese economy. He did not talk about his A-bomb experience openly out of concern over possible discrimination toward his son and daughter. After they got married, he joined the activities of the Fukushima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, and, since 1981, has served as president of the organization.

Opposing continued use of nuclear power plants

In the 1980s, the number of members in the organization was about 150, twice as many as today. Many of the members were men who were exposed to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima after being assigned there while conscripted in the military. Not a few were workers, or had family members who were workers, at the nuclear plant in Fukushima or its related companies since the plant began operations in 1971. To avoid a split in the organization, the decision was made to “distinguish nuclear energy from nuclear weapons and not oppose nuclear power plants.”

In 1995, the organization published a book titled Senko no Hi kara 50-nen (Fifty Years Since the Flash of the A-bomb) which brought together the A-bomb accounts of 27 people, but no misgivings were then expressed about the nature of nuclear power plants.

In his preface as president, Mr. Yamada stressed the immediate elimination of nuclear weapons, calling them weapons of “cruel and indiscriminate mass killing,” and touched upon the importance of “transitioning to a peaceful way of living.”

But after the nuclear accident, the policy of “not opposing nuclear power plants” underwent a complete reversal. The Fukushima organization, along with the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), demanded that a new system be established by the Japanese government in which residents in the vicinity of the nuclear plant be able to undergo free medical check-ups. They urge: “We must not have generations which raise children while holding the same kind of anxiety and anguish experienced by the A-bomb survivors. Operations at nuclear power plants in Japan must not continue.” In spite of Mr. Yamada’s advancing age, he still gives talks to the public.

He hopes that the interest shown toward Fukushima will also translate into more interest in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The inhumane aspects of nuclear power are the same, he said. This month Mr. Yamada contributed his A-bomb account to the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims. “I’d be happy if it could be of some help,” he said. Although he spoke humbly, with his account sharing the thoughts he has reached after swings and turnabouts over many years, he feels a sharp difference in the level of interest between the people of Fukushima and the people of Hiroshima, his hometown, when it comes to the issue of nuclear energy.

(Originally published on April 14, 2015)