Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 9

Apr. 13, 2015

Live and Love published in 1989 to give voice to deaf survivors

Tomoe Kurokawa (née Nishida), 81, a former barber and resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima, agreed to an interview through a sign language interpreter 41 years after the atomic bombing. She now looked back on her feelings at the time she gave her testimony, sometimes communicating these reflections through writing: “I wanted someone to hear me. I was lonely. I felt relieved after telling my whole story.”

Ms. Kurokawa was born deaf. As a child, she learned to lip read and use sign language, but has always had difficulty conveying certain words, like “radioactivity.” Above all, she was busy with her daily life, raising her child and working at the barber shop after taking over the business from her late husband.

On August 6, 1945, Ms. Kurokawa was in Yoshida-cho (now the city of Akitakata), where the school for the deaf had relocated to escape air raids in Hiroshima. Ninety-eight elementary and secondary students lived with school staff at a temple in Yoshida-cho, and they went to the prefectural agricultural school which served as their temporary school building. She said, “I saw an enormous black and white cloud rising up in the sky in the direction of Hiroshima.” With sweeping movements of her hands, up and down and left and right, she shared her story.

Nursing her mother desperately

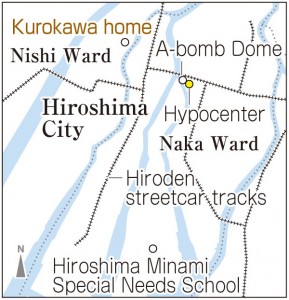

Ms. Kurokawa’s family lived in the Nakahiro district (now part of Nishi Ward). Her father Shizuma, who was 46 at the time, picked her up by bicycle after the bombing. On August 14, they returned to the burnt site of their home. Her sisters had been lightly wounded in the blast, but her mother Haruyo, then 43, lay in a bomb shelter, seriously injured.

In the book Live and Love, published in 1989 by the Hiroshima Prefecture Research Association for Sign Language Interpretation, Ms. Kurokawa vividly described their reunion.

“‘Mom. Mom.’ ‘Tomoe.’ She did nothing but nod her head. In tears, I gave her a drink of water which was trickling from a pipe on the burnt site of our house. I nursed her desperately.”

Three years later, her mother was back on her feet and Ms. Kurokawa returned to the Prefectural School for the Deaf (now the Hiroshima Minami Special Needs School in Naka Ward). She took a sewing course and also practiced cutting hair.

At the age of 20, she began living at a barber shop, and married the shop owner, Tamotsu. He was also deaf. After having a son, they built a dwelling with a barber shop in Eba Nihonmatsu (now part of Naka Ward). She lived there with her husband’s parents. In 1979, just when their loan for the home was almost paid off, Tamotsu fell ill and died at the age of 51.

His last words were, “I leave my parents to you.” With these words in mind, she ran the barber shop and took care of her in-laws until they passed away. In 1986, she met Fumie Nakagawa, 75, a sign language interpreter living in Minami Ward, and, despite her busy days, accepted the request for an interview.

Ms. Nakagawa’s parents were deaf and she grew up learning sign language before spoken Japanese. Even so, she says that it isn’t possible to capture the full richness of sign language, with its gestures and facial expressions, into written words. At the same time, she was spurred by the desire: “If I don’t do anything, there will be no record of the experience or existence of the deaf survivors.”

Raising a monument to remember the victims

Fifteen deaf people including repatriates from China and Russia, 11 of whom survived the atomic bombing, were interviewed about their war experiences from 1983 to 1987, and Live and Love was compiled as a collection of war and A-bomb accounts.

In addition, in cooperation with deaf survivors, Ms. Nakagawa raised a monument in 2003 at today’s Hiroshima Minami Special Needs School to remember the deaf A-bomb victims. The City of Hiroshima has not investigated the matter of deaf victims of the bombing, and the entire picture of the damage remains unclear, but 117 deaf people who experienced the A-bomb attack are reported to have died by the end of 2013. Of the deaf A-bomb survivors who offered their accounts for the collection, Ms. Kurokawa is the only one still living.

Ms. Kurokawa closed her barber shop five years ago because the site was part of the construction plans for the Hiroshima South Road. Now she lives with her son’s family and has four grandchildren. When she leaves the house, she must use a wheelchair, but she visits a social welfare facility operated by a Hiroshima organization for the hearing-impaired. She unfolds paper cranes sent to the A-bombed city and makes recycled paper which appeals for peace.

Ms. Kurokawa, who agreed to be interviewed again for this article, paid a visit to the monument at her old school with Ms. Nakagawa. It is still hard to say if the existence of the deaf survivors has been made known during the rebirth of the city. Ms. Kurokawa moved her hands up and down over her chest in front of the monument, engraved with the words, “for the repose of these souls.”

Interpreting for Ms. Kurokawa, Ms. Nakagawa said, “The dead are happy that there is also a monument for the deaf A-bomb victims.”

(Originally published on March 23, 2015)