Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Depicting the A-bombing 5

Oct. 29, 2014

Nurse student saw a “battlefield” in the dark hospital ward

Window frames warped by the blast of the atomic bombing stand on the south side of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors’ Hospital in Naka Ward. When the new hospital building was constructed, they were moved from the side of the front entrance to this location in June 2013. Gazing at this monument that conveys the scars of the atomic bombing, Yoshie Watanabe, 86, a resident of Hirosekita-machi, Naka Ward, said in frustration, “The atomic bombing was much more than this.”

The wounded flood into the hospital

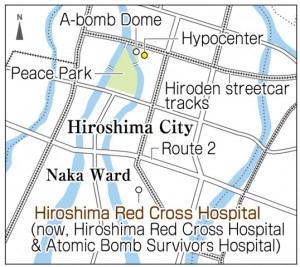

The former Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, also an army hospital at the time, was located about 1.5 kilometers to the south of the hypocenter. Casualties at the hospital included 56 deaths and 364 who were injured, but the three-story ferroconcrete main building did not burn down. Survivors flooded into the hospital in the aftermath of the blast, and Mrs. Watanabe was in the middle of it. She was just 17 and a student nurse.

Her maiden name was Yoshie Yoneima. In April 1945, she graduated from a girls’ high school in Kure, her hometown, and entered the nursing school attached to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. As the war deteriorated, the training program was shortened to two years, but she acquired the minimum nursing techniques needed for the battlefield, such as disinfecting and bandaging wounds.

On August 6, Mrs. Watanabe finished breakfast and returned to her room on the second floor of the wooden dormitory on the grounds of the hospital. When the bomb exploded, she became trapped under the collapsed building. Before it was engulfed in fire, she managed to crawl out of the wreckage and ventured into the main building. Together with classmates who also survived, she cleared the floor, moving aside the debris of the fallen ceiling and walls. As the wounded came streaming into the hospital, they were laid there on the floor.

Mrs. Watanabe herself was stung by glass fragments that dotted her head and arms, and she fainted a number of times. The next day, her father came from Kure to find her, then took her home. For the following days she lay there in bed. On August 21, after the war had ended, she went back to Hiroshima in order to change her residence certificate so that she could receive rations in Kure.

But Mrs. Watanabe saw that rain and wind could not be prevented from blowing into the hospital through the bent and empty window frames, and that Fumio Shigeto, the deputy director of the hospital, and the nursing students were busily working. When she saw this, she decided to stay and pitch in. Dr. Shigeto later became director of the Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital, too. (He passed away in 1982 at the age of 79.)

There was not much they could do to treat the terrible burns which exposed red flesh, except to dab alcohol on them with bits of cotton. Mrs. Watanabe scooped water in her hands for a mother who asked for some, but when she returned, the woman was already dead. “The baby she was holding in her arms was dead, too,” Mrs. Watanabe recalled. The nursing students, wearing work pants made of kimono material and white caps, rested in the hallways and on the stairs.

The dead were cremated one after another on the hospital grounds. The fires burning the bodies lit up the dark hospital rooms. Even though the war was over, it was a battlefield. At the urging of her father, Mrs. Watanabe left Hiroshima again on September 12. By then she was suffering from hair loss and bleeding, signs of radiation sickness.

Ashamed to give up her career

Mrs. Watanabe felt ashamed that she gave up her career in nursing, though reluctantly. When she was 19, she wed in an arranged marriage and worked at an insurance company while raising two children. By the time she retired, she had become the manager of a sales office in Hiroshima.

For many years, Mrs. Watanabe did not think she was qualified to talk about her experience of the atomic bombing. The former main building of the Red Cross Hospital, which played a central role in treating A-bomb survivors in the aftermath of the bombing, was dismantled in 1993, and the window frames on the northwest corner of the third floor were turned into a memorial. With the changing times, she thought that the demolition of the old building could not be helped. However, when she was 74, she learned about an appeal for pictures of the atomic bombing made by survivors. She felt she had to produce some pictures in order to record what she had witnessed.

Mrs. Watanabe drew three pictures with her grandchildren’s crayons: one scene at night when she made the rounds of the hospital with a candle as a student nurse; another scene of herself trapped under the collapsed dormitory; and another of people crowded into the hospital. On the back of one picture, she wrote, “War is an act of demons.”

Mrs. Watanabe laments that these pictures cannot convey even one-tenth of what she saw, but her eldest daughter, Miwako Aniya, 65, who lives with Mrs. Watanabe, said, “What the pictures show is beyond what I had imagined from the things my mother told me since my childhood.”

During our interview, Mrs. Watanabe wondered many times whether politicians truly understand the cruelty of war as they sound only perfunctory when they say they seek to protect peace. She has four grandchildren now.

At the time of the atomic bombing, there were 408 first-year and second-year students at the nursing school, and 22 died in the blast. Twenty-eight of the students who graduated from the school are alive today. The number of people able to provide personal accounts of the bombing is dwindling. The pictures drawn by Mrs. Watanabe show the “battlefield” which resulted from the bombing, with even the hospital not out of bounds, as well as the medical efforts made in the aftermath.

(Originally published on October 6, 2014)