Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Mobilized Students 1

Jun. 10, 2015

Report on deaths of high school students

While the city’s administrative functions were thoroughly decimated by the atomic bombing, Shintoku Girls’ High School compiled a report running 220 pages on the victims of that school. The report was apparently made by gathering information from the relatives of students and staff members. Many of the entries in this record were made around November 1945. Today, it looks as if the sheets of paper would tear to the touch.

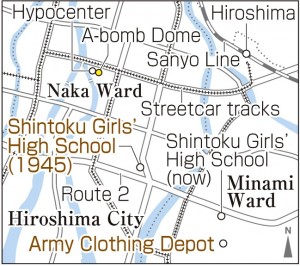

One name in the report is Michiko Hori, a girl who was then 13. The entry about her says that she was evacuated to the school grounds of the high school, which was located in the Minamitakeya area (now Naka Ward). The date of her death is listed only as “The 20th year of Showa (1945),” lacking a specific day. The name “Chieto Hori” is noted as a family member.

This was the first time that Kazuaki Hori, 82, saw the record of his sister’s death. “My father (Chieto) searched for my sister, but he died three years later at the age of 42,” he said. Shizuko Matsunaga (nee Tsukumo), 83, a friend of Michiko’s, said, “I’ll always remember her cute smile.” Both Michiko and Ms. Matsunaga attended Senda National School (now Senda Elementary School in Naka Ward) and entered Shintoku Girl’s High School.

Mr. Hori wanted to find out how his sister spent her days as a mobilized student, and Ms. Matsunaga wished to learn how her friend had died. Together they visited the school, which gave them special permission to access the report.

Believing that Japan would win the war

Ms. Matsunaga still clearly remembers the scene when she and Michiko were involved in a performance of military music and classical Japanese dance in the auditorium. It was December 8, 1944, the third anniversary of the day Japan began waging war against the United States and the United Kingdom. The older students of the school, who were working at munitions factories and other locations year-round, came to school for the first time in many months. A ceremony was held to show appreciation for their service to the nation. Ms. Matsunaga and Michiko practiced the music and dancing, all the while believing that Japan would win the war.

After they became second-year students, Michiko and her classmates started helping with the production of tobacco at the Hiroshima District Monopoly Bureau, which was located in today’s Minami Ward, or doing farm work outside the city.

Chieto worked for the Army Clothing Depot. As a precaution against air raids, the Army Clothing Depot opened an office in today’s city of Higashihiroshima because workers were relocating temporarily to the countryside, a development that began in May 1945. Mr. Hori, then a sixth-grader at Senda National School, joined this evacuation, but Michiko stayed in the dormitory near her school.

On August 6, 1945, the second-year students of the girls’ high school gathered on the school grounds, located about 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. They were set to depart for their work assignment, helping to dismantle homes to create a fire lane in the Tsurumi area (now Naka Ward), when the atomic bomb exploded.

“The parents of students in the dormitory brought shovels and searched for their children’s remains. I could hardly bear to look at them,” wrote Yazo Watanabe, the vice principal of the school, in the school log, describing the terrible sight.

The number of victims among the students of Shintoku Girls’ High School reached 405, and 196 of these deaths were second-year students.

Michiko was found by her parents on August 9 at a warehouse of the former Army Clothing Depot, which still stands in the Deshio area of Minami Ward, but she had already passed away. “My mother heard that Michiko was waiting for her father to come and would ask the people around her, ‘Isn’t that my dad?’ My mother always regretted that she couldn’t find her in time,” said Mr. Hori.

Mr. Hori’s mother Shizue told him what happened on August 5, the day before the bombing. (Shizue Hori died in 2003 at the age of 91.) Michiko had the day off, and she visited her mother at her temporary residence in the suburbs. “It was very rare of Michiko to show any sign of weakness,” recalled Mr. Hori, “but that day she complained to Mother and looked back at her again and again when she was leaving for Hiroshima.”

Serving as a substitute for her mother, Ms. Matsunaga was helping to make a fire lane in the Minami Senda area (now Naka Ward) when the bomb exploded. A week later, she and four other students and teachers collected numerous bones and brought them to Jisenji Temple (now part of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park).

Though she survived the A-bomb blast, Ms. Matsunaga was unable to escape the bomb’s effects. She developed breast cancer at the age of 39 and underwent surgery. A former classmate was struck by cancer at around the same time and died. Driven by emotions she finds difficult to put into words, she began sharing her A-bomb account while in her 50s, hoping to be of some help. Three years ago, she was appointed a “Special Communicator for a World without Nuclear Weapons” by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and has since taken part in a speaking tour around the world.

Making the record accessible

Mr. Hori was an elementary school teacher and told his students about his experience living in the countryside to avoid air raids and his sister’s death. When he saw the report on the deaths of his sister and other students, he felt that this record should be made public and used well. He feels it is also a record of the sorrow of parents, friends, and teachers.

Ms. Matsunaga learned about Michiko’s death from Mr. Hori. Her husband, who died four years ago, once sought to join the Imperial Japanese Navy. “No war!” she said with a grave look. Then she smiled and added, “I will continue telling my story for as long as my health allows.”

◇

There was only a razor-thin difference between life and death in the atomic bombing. The experiences of the mobilized students enable us to reflect on the past and consider our future.

(Originally published on June 8, 2015)