1. Paradise Lost

Feb. 15, 2013

Chapter 3: The Central, South Pacific and Australia

Part 3: The French Cover-up in Polynesia

Part 3: The French Cover-up in Polynesia

The islands of Polynesia are known as the jewels of the South Pacific and have often been described as the last paradise on earth. Since the government of Charles de Gaulle turned the area into a nuclear testing site in 1966, over 150 hydrogen and atomic bomb tests have been carried out, and testing still continues in the South Pacific to this day. We traveled there to find out what was really going on behind the idyllic tropical facade of those islands forced to coexist with the bomb.

1. Paradise Lost

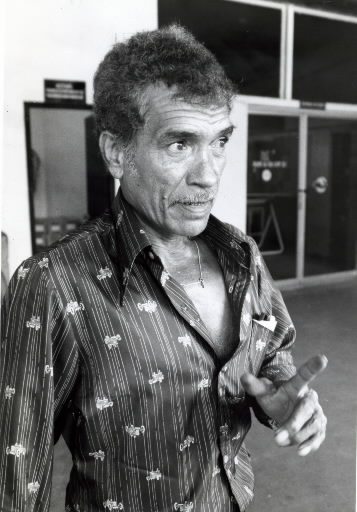

Stepping out into the bright sunlight at Faa'a Airport, gateway to French Polynesia, we felt the rush of a light sea breeze. To the accompaniment of guitar and ukulele music smiling young women in traditional Tahitian costume handed out bright red flowers. It was truly the kind of welcome one would expect when arriving in a tropical paradise. Unfortunately, this is only one face of Polynesia. James, a resident of the islands whom we chanced to meet near the airport, took two yellowing photographs out of a crumpled paper bag and showed them to us, taking care first to ensure that nobody was watching.

"Take a look at these," James said. "I took them secretly in July 1973, when I was working at Moruroa." The photos showed a black object hanging from the undercarriage of an airship. "It's an atomic bomb, that's what it is." So saying he lowered his voice and began to tell his story.

During the period from 1965, a year before testing began, until 1980, James had gone to Moruroa many times to work on the wharf there. "Not long after the tests began, a lot of the other guys came down with this mysterious illness. After that the navy started to tell us not to eat the fish or drink the coconut juice."

Convinced that the bombs were the cause, James defied regulations and took the two photos as evidence. Afraid of repercussions from the navy, he has kept them well hidden. "This is the first time I've shown them to anybody," he said. "I figured that you'll believe me because you're from Hiroshima."

During our stay in Tahiti, we spoke once more with James. It was in front of the statue of Pouvanaa'a Oopa, on the occasion of the annual May memorial service for the Polynesian hero.

"Oopa was the leader of the Polynesian independence movement, as well as the antinuclear movement. He was the man who stood up to de Gaulle. The French did all they could to silence him—they even threw him in a French jail for eleven years," James said. The atmosphere at the service was solemn, but there was no mistaking the determination on the faces of those who stood in front of the statue.

"It takes courage to talk about Moruroa here," James said in a low voice. "If the French authorities find out, you lose your job pretty damn fast."

Some of the people standing around us nodded in agreement. These are the islands where Gauguin spent the latter part of his life and where the romantic scenes of the musical South Pacific were set. But if you open your eyes and ears you can see the gloom and hear the stifled anguish of a people born in a tropical paradise but living within the shadow of the atomic bomb. Slowly but surely, the islanders and their way of life are falling a victim to French nuclear autonomy.

Soon after our return to Japan, a report came from New Zealand that the fourth underground test for that year (1989) had been carried out at Fagataufa Atoll, bringing the total number of tests to 107. We got in touch with our acquaintances in Tahiti, only to find that nobody knew about the test. There are 160,000 Polynesians living on more than 310 islands scattered over this vast stretch of ocean large enough to contain the whole continent of Europe. The knowledge of what nuclear testing can do to the environment is, however, still confined to a small minority of these people.

It was clear that the fastest way to find out about the effects of the tests on the local people was to investigate for ourselves by traveling to the islands surrounding Moruroa. However, it is difficult to get into Polynesia itself for any reason other than sightseeing, let alone obtain permission from the French government to enter the test area. We had no choice, therefore, but to stay in Tahiti and speak to those who had seen the site. One such person was Edward, who was the only Polynesian to have been involved in the checking of radiation levels at the Moruroa test site. He worked at Moruroa for twelve years, from the time of the first tests. Believing the French assurances that there was no danger, he worked in the radioactive contamination survey unit, and, on approximately thirty occasions over the next seven years, walked around the atoll directly after bomb tests.

The surveys were always carried out the day after a test. From a warship waiting outside the area designated as dangerous, the four members of the survey team would travel by helicopter to the contaminated area. There they would don protective clothing and gas masks, and walk around the site using a geiger counter to measure the level of radioactivity.

"When we flicked the switch on the counter it would just let out a continuous high-pitched scream. It was particularly bad in the northern part of the group where tests had been carried out many times. The worst areas we had to fence off and put up No Entry signs. At times half of the thirty-mile length of the atoll was designated as off-limits."

We couldn't help but shiver, recalling the glistening white beaches of the atolls that we had admired from the plane.

"There were some workers whose hair suddenly fell out, then they died soon after. Others ate shellfish and died in terrible pain, driven mad by the itching. Their families were sworn to silence, and their coworkers are too afraid to say anything for fear of losing their jobs," Edward continued. One cannot say with absolute certainty that these people were killed by radiation, but there is a strong possibility that exposure to high levels of radiation was the cause of their deaths.

Edward also informed us that radioactive contamination had spread beyond Moruroa to the island of Mangareva, which lies 225 miles east of the test site and has a population of five hundred. When he traveled with the survey team to the area, Edward found that the levels of contamination in migratory fish were particularly high. It does not take a great deal of imagination to link this fact to the secondary radiation exposure of the islanders. The French government expanded its investigations to encompass a wider area, at the same time consistently denying to the rest of the world that the tests had any negative effects.

This complete suppression of all information regarding the tests left the local people with nothing but rumors to rely on. However, it has also led other nations on the Pacific Rim to launch their own investigations in the interests of national security. In Western Samoa, more than two thousand miles west of Moruroa, a New Zealand government observation post recorded that the level of radioactivity in rainwater there was found to be 13,500 picocuries per liter after the detonation of a bomb at Moruroa in the presence of President de Gaulle on September 11, 1966. The bomb was equivalent to eight Hiroshimas.

The same high levels of radiation were detected in the Cook Islands and Fiji, also a long way from Moruroa, so it may be concluded that an even greater quantity of radioactive fallout must have contaminated French Polynesia.

Surveys by neighboring countries showed that the level of contamination in the atmosphere was the same in 1971 as in 1963, the year in which plutonium-producing nations were hurrying to conduct as many tests as they could before the signing of a treaty which would bring about a partial reduction in nuclear testing.

France, which for many years had ignored the treaty, was finally forced to give in to international pressure in 1975, and in that year switched from atmospheric to underground testing.