5. Double Exposure

Mar. 25, 2013

Chapter 5: Britain and France

Part 1: The Rough Road to Nuclear Supremacy

Part 1: The Rough Road to Nuclear Supremacy

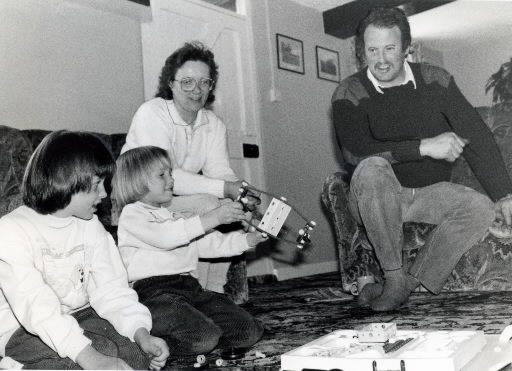

The farms around Sellafield were also on the receiving end of contamination from the plant. Those that we visited had suffered doubly, having also been affected by fallout from Chernobyl. James Phizacklea stood over six feet tall and was solidly built. It was not difficult to imagine that he was a former rugby player. He was the very picture of health. Or so it seemed. "These last few years I've started having all sorts of aches and pains," he told us. "And it's not just me but my daughter Jennifer, too; she's got leukemia."

The Phizacklea family owns a sheep and dairy farm five miles east of Sellafield. James recalled that his father had been forced to dump milk for months after the fire at Windscale in 1957. James took over the running of the farm with his wife, Ann; they have two daughters: Laura, aged seven, and Jennifer, aged five. Their peaceful life style was first disrupted in 1986:

"I remember it was just after New Year. James got these big lumps on his arms. And he was tired all the time—he'd go out to work on the farm, but come back soon after and sit down saying how exhausted he was. He had a thorough examination, but we're still not sure what caused it," recalled Ann, a former nurse.

Later in the year, the area became contaminated by cesium-137 from the accident at Chernobyl in April.

"Five days later, on May 1, it rained. The pasture needed a bit of rain, so I was happy as anything of course... If only I'd known." Phizacklea looked tired all of a sudden as if the memory was too much for him. The level of cesium contamination on the farm reached 17,000 becquerels per square meter. The animals recorded equally high levels.

Under British law, meat with a reading of 1,000 becquerels or more per kilogram cannot be sold. Every one of Phizacklea's stock is over this limit. Before the accident, he had one hundred milking cows. A year later he reduced the number to twenty; it was too difficult to get hold of uncontaminated feed, and the amount of milk consumed had decreased drastically due to the public's fear of radiation since the accidents. The farm was suffering yet again from the effects of radiation; but this time from a nuclear power plant not five but 1,350 miles away, and the government refused to provide any compensation.

In the summer of that same year came the last straw. Jennifer, only two at the time, was found to have leukemia.

"When I heard it was leukemia, the first thing I thought of was Sellafield," said Ann. "The smoke from that place passes over our house all the time. Plus there was Chernobyl, of course. I know it's almost impossible to prove, but you can't deny that having a nuclear fuel reprocessing plant on your doorstep must have some effect."

Her husband had always believed that as long as a nuclear power plant was run properly, there would be no problems. In 1976 he had even worked as a turbine operator at Sellafield himself. Now, however, he occasionally wonders whether he was exposed to radiation during that twelve-month period, although there is no way he can prove that the illness which has now spread from his arms to his legs was caused by radiation.

Jennifer's leukemia is in remission after two and a half years of treatment. However, the uncertainty of not knowing when she will be struck down again, combined with James's mysterious illness and the cesium contamination of the farm, add up to a terrible burden for the family. Bitter experience has left them firm in the belief that nuclear power plants are far from safe. "As far as we're concerned, Sellafield and Chernobyl have committed the same crime. How are farmers supposed to make a living when they can't even produce food that people feel safe about eating?"