- A-bomb Images

- Record of Hiroshima: Reconstruction after atomic bombing

Record of Hiroshima: Reconstruction after atomic bombing

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Major undertaking involving all citizens

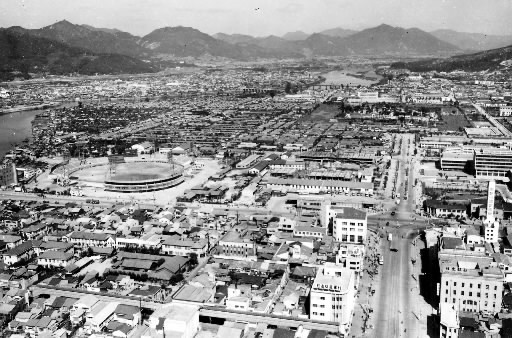

More than 300,000 people experienced the horrific destruction unleashed by a single atomic bomb that exploded in the sky above Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. By the end of that year, the death toll had reached 140,000 +/- 10,000, according to an estimate submitted by the City of Hiroshima to the United Nations in 1976. Almost all of the 45,100 buildings within a two-kilometer radius of the hypocenter were completely destroyed and burned to ash. It was amid this world of death that Hiroshima set out on its road to recovery. The late Shinso Hamai, an A-bomb survivor and the city’s first popularly elected mayor, sought to rebuild the city, once stating that he hoped to make Hiroshima a city of ideals as a farewell gift to those who perished in the bombing. To realize this wish, he was forced to tread a thorny path. This article will trace the history of Hiroshima’s reconstruction after the atomic bombing through photos taken by staff members of the Chugoku Shimbun.

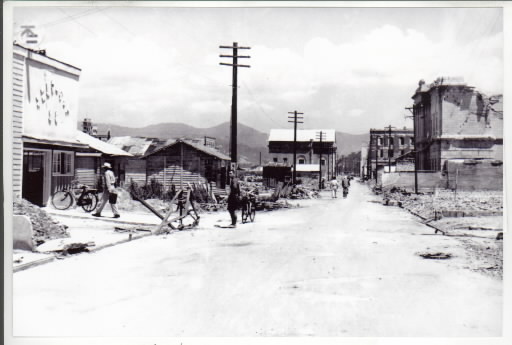

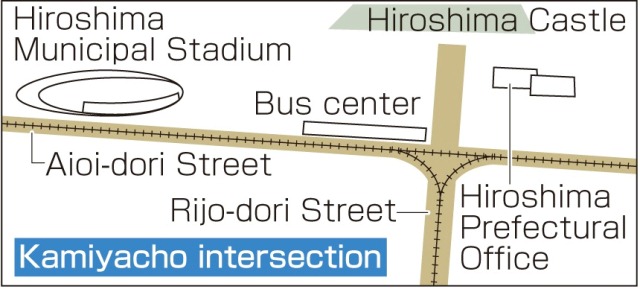

Toshiaki Tanaka, 87, was one of the first to reopen a shop in the ravaged city. He still runs a liquor store in the Ushita-honmachi district in Higashi Ward. He shared a photo taken when he lived in a tent on the south side of what has become the Kamiyacho intersection, now surrounded by high-rise buildings. “That is where I was born, and I had nowhere else to go,” Mr. Tanaka said. His home was in the Saiku-machi area, right beneath the exploding bomb. He lost his parents, his wife, and his 1-year-old daughter. At the time of the blast, he had been mobilized for work at the Imperial Japanese Army Shipping Command in Minami Ward.

Mr. Tanaka began living in a tent in December 1945, and in February of the following year, he built a shack of less than 33 square meters, which doubled as a residence and store. With other surviving shopkeepers, he opened a supply station, which offered soy sauce, vegetables, and sake. “We could use tap water freely,” he said. “And a handy friend of mine installed electricity.” But there were few customers.

Mr. Tanaka was in charge of the Otemachi and Fukuromachi areas, but he recalls that there were only 63 people in need of goods, half of them workers of the city government. There were also robbers and pickpockets, and gun battles were not uncommon. According to Mr. Tanaka, around the time the bus center opened, 12 years after the bombing, stability was finally restored and the bustle of the streets returned.

Ikimi Kikkawa, 83, a resident of Naka Ward, ran a souvenir shop near the A-bomb Dome.

Her husband Kiyoshi was interviewed by Life magazine in 1947 when he was being treated at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. (Kiyoshi died in 1986.) Because of severe scarring, he was dubbed “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1.” Many people from home and abroad came to see him at the hospital, but the couple had nowhere to go when he left the hospital in 1951.

“We couldn’t find work, so we opened a shop. He said he would work his way up from the bottom, no matter what,” Ms. Kikkawa said. Calling it Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1’s shop, the A-bomb survivors’ movement was launched and expanded from this location. When Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, where the Atomic Bomb Dome now stands, was constructed, they followed the eviction notice for this area of 12.2 hectares and closed their shop in 1969. The city planned to make this park a sacred place.

What was involved in the reconstruction of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing? Shunichi Matsubayashi, 61, a resident of the Kamezaki area of Asakita Ward, took part in compiling the city’s books to mark the forty- and fifty-year history that followed the A-bomb attack. He describes the reconstruction as “a major undertaking that was accomplished with the joint strength of all the residents, like sumo wrestlers demonstrating their power.”

In retrospect, both the mayor and the members of the city assembly took strong action to gain support from the national government. Their many efforts bore fruit when the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Act was enacted in 1949 after earning the approval of 91 percent of the voters in the first referendum held in Japan.

Thirty-four hectares of former military land was returned, without charge, to the city, and the amount of governmental subsidy for the construction of Peace Memorial Park was increased. Yet with the designated area for reconstruction about two-thirds of the delta, or 1,060 hectares, the development of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City remained a rocky road with some citizens, struggling to survive from day to day, who responded angrily to the plan.

Mr. Matsubayashi said that Hiroshima’s “DNA” is found in the process of reconstruction following the devastating impact of the atomic bombing.

“It’s impossible to revive the dead or to heal the emotional wounds created by the bombing,” he said. “This is exactly why our predecessors stood up to build a city where people express their wish for peace to the world. Can we say that we’ve inherited their conviction and their legacy?” Resurrecting the memories of reconstruction means handing down this legacy to future generations.

(Originally published on April 30, 2005)

Major undertaking involving all citizens

More than 300,000 people experienced the horrific destruction unleashed by a single atomic bomb that exploded in the sky above Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. By the end of that year, the death toll had reached 140,000 +/- 10,000, according to an estimate submitted by the City of Hiroshima to the United Nations in 1976. Almost all of the 45,100 buildings within a two-kilometer radius of the hypocenter were completely destroyed and burned to ash. It was amid this world of death that Hiroshima set out on its road to recovery. The late Shinso Hamai, an A-bomb survivor and the city’s first popularly elected mayor, sought to rebuild the city, once stating that he hoped to make Hiroshima a city of ideals as a farewell gift to those who perished in the bombing. To realize this wish, he was forced to tread a thorny path. This article will trace the history of Hiroshima’s reconstruction after the atomic bombing through photos taken by staff members of the Chugoku Shimbun.

Toshiaki Tanaka, 87, was one of the first to reopen a shop in the ravaged city. He still runs a liquor store in the Ushita-honmachi district in Higashi Ward. He shared a photo taken when he lived in a tent on the south side of what has become the Kamiyacho intersection, now surrounded by high-rise buildings. “That is where I was born, and I had nowhere else to go,” Mr. Tanaka said. His home was in the Saiku-machi area, right beneath the exploding bomb. He lost his parents, his wife, and his 1-year-old daughter. At the time of the blast, he had been mobilized for work at the Imperial Japanese Army Shipping Command in Minami Ward.

Mr. Tanaka began living in a tent in December 1945, and in February of the following year, he built a shack of less than 33 square meters, which doubled as a residence and store. With other surviving shopkeepers, he opened a supply station, which offered soy sauce, vegetables, and sake. “We could use tap water freely,” he said. “And a handy friend of mine installed electricity.” But there were few customers.

Mr. Tanaka was in charge of the Otemachi and Fukuromachi areas, but he recalls that there were only 63 people in need of goods, half of them workers of the city government. There were also robbers and pickpockets, and gun battles were not uncommon. According to Mr. Tanaka, around the time the bus center opened, 12 years after the bombing, stability was finally restored and the bustle of the streets returned.

Ikimi Kikkawa, 83, a resident of Naka Ward, ran a souvenir shop near the A-bomb Dome.

Her husband Kiyoshi was interviewed by Life magazine in 1947 when he was being treated at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. (Kiyoshi died in 1986.) Because of severe scarring, he was dubbed “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1.” Many people from home and abroad came to see him at the hospital, but the couple had nowhere to go when he left the hospital in 1951.

“We couldn’t find work, so we opened a shop. He said he would work his way up from the bottom, no matter what,” Ms. Kikkawa said. Calling it Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1’s shop, the A-bomb survivors’ movement was launched and expanded from this location. When Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, where the Atomic Bomb Dome now stands, was constructed, they followed the eviction notice for this area of 12.2 hectares and closed their shop in 1969. The city planned to make this park a sacred place.

What was involved in the reconstruction of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing? Shunichi Matsubayashi, 61, a resident of the Kamezaki area of Asakita Ward, took part in compiling the city’s books to mark the forty- and fifty-year history that followed the A-bomb attack. He describes the reconstruction as “a major undertaking that was accomplished with the joint strength of all the residents, like sumo wrestlers demonstrating their power.”

In retrospect, both the mayor and the members of the city assembly took strong action to gain support from the national government. Their many efforts bore fruit when the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Act was enacted in 1949 after earning the approval of 91 percent of the voters in the first referendum held in Japan.

Thirty-four hectares of former military land was returned, without charge, to the city, and the amount of governmental subsidy for the construction of Peace Memorial Park was increased. Yet with the designated area for reconstruction about two-thirds of the delta, or 1,060 hectares, the development of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City remained a rocky road with some citizens, struggling to survive from day to day, who responded angrily to the plan.

Mr. Matsubayashi said that Hiroshima’s “DNA” is found in the process of reconstruction following the devastating impact of the atomic bombing.

“It’s impossible to revive the dead or to heal the emotional wounds created by the bombing,” he said. “This is exactly why our predecessors stood up to build a city where people express their wish for peace to the world. Can we say that we’ve inherited their conviction and their legacy?” Resurrecting the memories of reconstruction means handing down this legacy to future generations.

(Originally published on April 30, 2005)