- A-bomb Images

- Record of Hiroshima: Pursuing the lost “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing”

Record of Hiroshima: Pursuing the lost “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing”

Selected in 1947, they did not include the A-bomb Dome

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

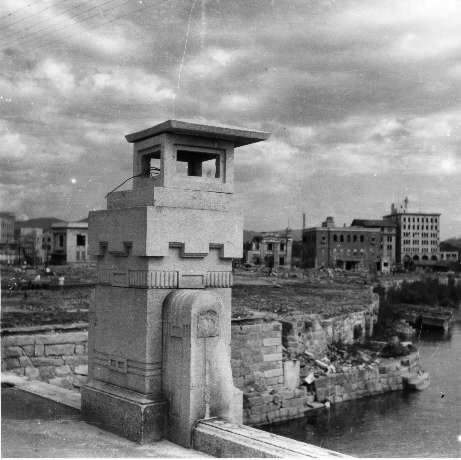

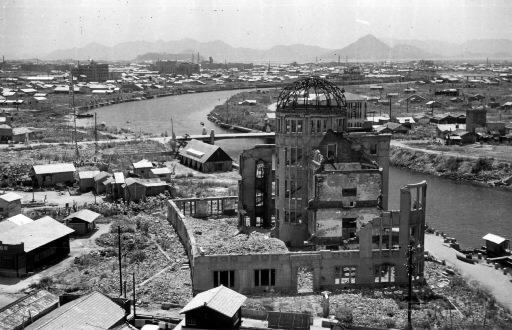

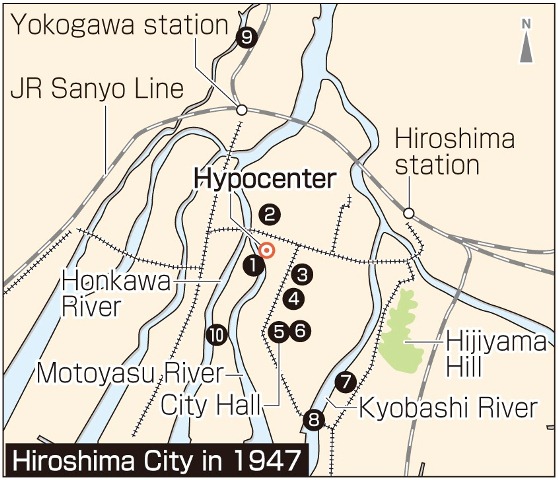

This photo shows the heart of Hiroshima in 1947, two years after the atomic bombing, around the area which later became Peace Memorial Park. That year the first “Peace Festival” was held in the former Nakajima District, located across the river from the Atomic Bomb Dome. This festival was the forerunner of the city’s Peace Memorial Ceremony, which has continued every year up to today. At this event in 1947, the “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing” were deemed A-bomb monuments in an effort to convey the facts of the atomic bombing at a time when the reconstruction of the city had just begun.

The goal behind selecting the Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing was to preserve the unique features of the A-bomb damage and help attract visitors to the city. The A-bomb Dome, though now a World Heritage site, was not chosen to be among these ten. Why not? This article looks at the unknown facts behind the lost Ten Views. Their selection was the starting point for preserving A-bombed structures in order to hand down the facts of the atomic bombing to future generations.

Unearthing the Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing

Efforts to convey the consequences of the atomic bombing began as the devastated was undergoing reconstruction. In 1947, the City of Hiroshima selected the Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing. In retrospect, it seems curious that the A-bomb Dome was not chosen, while some “odd” things were. Still, the Ten Views embodied the desire of the citizens who had endured the tragedy of the atomic bombing. Preserving A-bombed artifacts was also proposed by an Australian national who was serving as an advisor for the city’s reconstruction.

On August 11, 1947, the article with the large headline “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing to be Conveyed to the Future” appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun. It read: “The City of Hiroshima will seek to preserve interesting artifacts that show unique features of the damage caused by the atomic bombing in order to convey the magnitude of the bombing and help attract visitors to the city.”

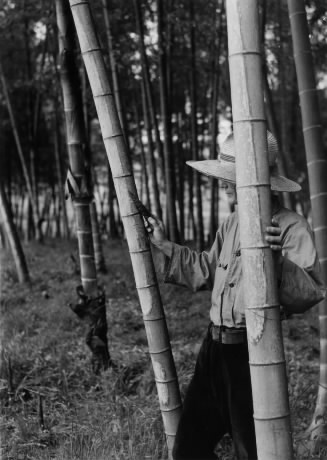

The selection of some of these artifacts, though, such as number five, “A piece of cloth on the third floor of City Hall,” raises questions. Even local people would have difficulty finding some of them, including number nine, “A bamboo forest in Misasa.” In those days, the morning newspaper consisted of just two pages, due to a paper shortage. Although this was a large article, it carried no photos of the Ten Views.

When the City of Hiroshima was developing its reconstruction plans, including road planning and land readjustment, who proposed preserving these things that showed the effects of the atomic bombing? Shigeteru Shibata, the deputy mayor at the time of the bombing, wrote in his book Genbaku no Jisso [“The Facts of the Atomic Bombing”], published in 1955: “These items were found and listed by Mr. Ono, who was working at the office of the Director General of the Reconstruction Bureau.”

“Mr. Ono” was Masaru Ono, who had held different jobs, including a stint as a newspaper reporter, before joining the city’s Reconstruction Bureau after the atomic bombing. He died 13 years ago at the age of 89. When he was 76, he wrote:

“Mr. Nagashima [Satoshi Nagashima, the first Director General of the Reconstruction Bureau] and I found strange phenomena as we were going around the devastated city. In 1947, after the Peace Festival [today’s Peace Memorial Ceremony, which started that year], a newspaper reporter from the City Hall press club asked if I had any stories. So I told him about the Ten Views...” This news then attracted public attention.

Kazuya Yamashita, 49, a city planner who has extensive knowledge of the A-bombed buildings in Hiroshima, says, “The reason they chose things not only in the city center but also in places outside the area that was completely destroyed and burned, such as Miyuki Bridge and a bamboo forest in Misasa, is because they wanted to convey the tremendous damage caused by the atomic bombing. Since the whole city was devastated, they probably paid attention to the unique and detailed features of the destruction.”

The Ten Views do not include the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, which came to be known as the A-bomb Dome in the 1950s. Shunichi Matsubayashi, 63, a former employee of the city government who was involved in the compilation of An Illustrated History of Postwar Hiroshima, sees the citizens’ sore feelings in the fact that the A-bomb Dome was not selected.

“There were people who wanted the building to be demolished because it reminded them of the horror of the atomic bomb. The Ten Views were chosen with people’s feelings in mind to mitigate the pain. Taking the preservation of history into account along with the reconstruction of the city was an ingenious idea,” says Mr. Matsubayashi. He believes this viewpoint is needed as well in today’s urban redevelopment.

The Ten Views were renamed the “Places of Interest Related to the Atomic Bomb.” The renewed list included additional structures such as the A-bomb Dome and the stone steps where a human shadow was seared due to the bomb’s heat rays. These steps were located at the entrance of the Hiroshima Branch of the former Sumitomo Bank. Meanwhile, the items connected to the city government were removed from the list. In all, 13 things made up the Places of Interest.

Selecting and preserving these Places of Interest Related to the Atomic Bomb were promoted by an Australian national stationed in Hiroshima as a member of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces. He served as an advisor on the reconstruction of the city.

“Major Jarvie proposes preservation of A-bomb monuments,” was the headline for an article that appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun on July 8, 1948. Major Stanley Archibald Jarvie proposed that the city preserve these places, which would also promote tourism. The 1949 Shisei-yoran, a guide to the city’s administration, took the position, for the first time, that the “Hypocenter, Industrial Promotion Hall” and other places were “A-bomb monuments to be preserved.” This was the year that the Peace Memorial City Construction Law was enacted, providing the foundation for the reconstruction of the city.

Major Jarvie, who was a building engineer, also proposed a reconstruction plan for the city to address the war damage. Norioki Ishimaru, a professor at Hiroshima International University, has studied the plan and notes that Major Jarvie served as an advisor to the city from September 1947 to May 1949. “Mr. Jarvie must have proposed that the city preserve structures that were appealing from a Western point of view,” he said. “He was personally acquainted with Kenzo Tange, who was designing Peace Memorial Park around an axis that passed through the A-bomb Dome.”

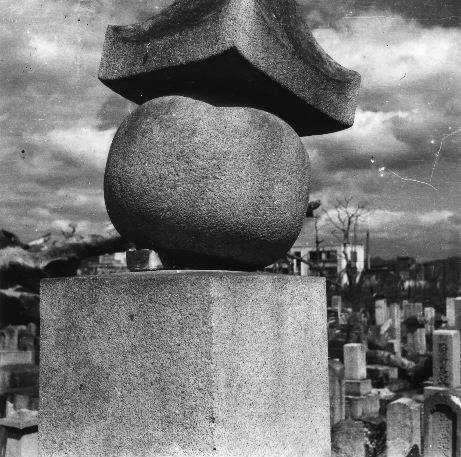

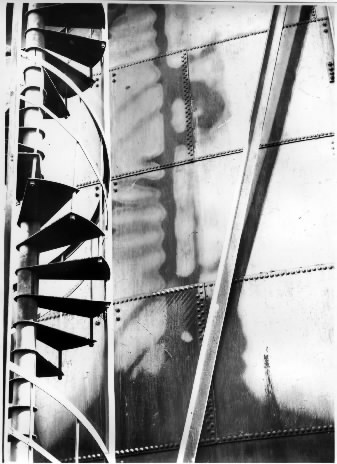

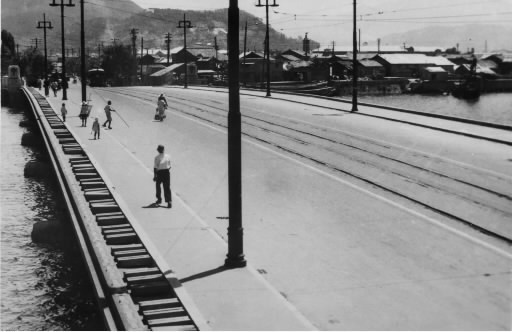

These efforts to preserve A-bombed buildings, including the A-bomb Dome, which became a World Heritage site in 1996, began from the initial idea of the Ten Views. During the reconstruction process, most of the Ten Views disappeared, but some photos taken at around the time they were chosen have been found among the historical items stored at the Chugoku Shimbun. On the back of the photos are stamps of the Yukan Hiroshima Shimbun [Evning Hiroshima Newspaper], which was published by an affiliated company. For the first in 60 years, they can all be identified.

Having confirmed dates and places from the original prints, and conducted interviews, we would like to share these photographs with the public. Permission has been obtained, from family members of the late photographers, for their use. The Yukan Hiroshima Shimbun was launched in June 1946, becoming the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun in April 1950. The captions of the pictures are from the Chugoku Shimbun of August 11, 1947.

(Originally published on April 30, 2007)

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

This photo shows the heart of Hiroshima in 1947, two years after the atomic bombing, around the area which later became Peace Memorial Park. That year the first “Peace Festival” was held in the former Nakajima District, located across the river from the Atomic Bomb Dome. This festival was the forerunner of the city’s Peace Memorial Ceremony, which has continued every year up to today. At this event in 1947, the “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing” were deemed A-bomb monuments in an effort to convey the facts of the atomic bombing at a time when the reconstruction of the city had just begun.

The goal behind selecting the Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing was to preserve the unique features of the A-bomb damage and help attract visitors to the city. The A-bomb Dome, though now a World Heritage site, was not chosen to be among these ten. Why not? This article looks at the unknown facts behind the lost Ten Views. Their selection was the starting point for preserving A-bombed structures in order to hand down the facts of the atomic bombing to future generations.

Unearthing the Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing

Efforts to convey the consequences of the atomic bombing began as the devastated was undergoing reconstruction. In 1947, the City of Hiroshima selected the Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing. In retrospect, it seems curious that the A-bomb Dome was not chosen, while some “odd” things were. Still, the Ten Views embodied the desire of the citizens who had endured the tragedy of the atomic bombing. Preserving A-bombed artifacts was also proposed by an Australian national who was serving as an advisor for the city’s reconstruction.

On August 11, 1947, the article with the large headline “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing to be Conveyed to the Future” appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun. It read: “The City of Hiroshima will seek to preserve interesting artifacts that show unique features of the damage caused by the atomic bombing in order to convey the magnitude of the bombing and help attract visitors to the city.”

The selection of some of these artifacts, though, such as number five, “A piece of cloth on the third floor of City Hall,” raises questions. Even local people would have difficulty finding some of them, including number nine, “A bamboo forest in Misasa.” In those days, the morning newspaper consisted of just two pages, due to a paper shortage. Although this was a large article, it carried no photos of the Ten Views.

When the City of Hiroshima was developing its reconstruction plans, including road planning and land readjustment, who proposed preserving these things that showed the effects of the atomic bombing? Shigeteru Shibata, the deputy mayor at the time of the bombing, wrote in his book Genbaku no Jisso [“The Facts of the Atomic Bombing”], published in 1955: “These items were found and listed by Mr. Ono, who was working at the office of the Director General of the Reconstruction Bureau.”

“Mr. Ono” was Masaru Ono, who had held different jobs, including a stint as a newspaper reporter, before joining the city’s Reconstruction Bureau after the atomic bombing. He died 13 years ago at the age of 89. When he was 76, he wrote:

“Mr. Nagashima [Satoshi Nagashima, the first Director General of the Reconstruction Bureau] and I found strange phenomena as we were going around the devastated city. In 1947, after the Peace Festival [today’s Peace Memorial Ceremony, which started that year], a newspaper reporter from the City Hall press club asked if I had any stories. So I told him about the Ten Views...” This news then attracted public attention.

Kazuya Yamashita, 49, a city planner who has extensive knowledge of the A-bombed buildings in Hiroshima, says, “The reason they chose things not only in the city center but also in places outside the area that was completely destroyed and burned, such as Miyuki Bridge and a bamboo forest in Misasa, is because they wanted to convey the tremendous damage caused by the atomic bombing. Since the whole city was devastated, they probably paid attention to the unique and detailed features of the destruction.”

The Ten Views do not include the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, which came to be known as the A-bomb Dome in the 1950s. Shunichi Matsubayashi, 63, a former employee of the city government who was involved in the compilation of An Illustrated History of Postwar Hiroshima, sees the citizens’ sore feelings in the fact that the A-bomb Dome was not selected.

“There were people who wanted the building to be demolished because it reminded them of the horror of the atomic bomb. The Ten Views were chosen with people’s feelings in mind to mitigate the pain. Taking the preservation of history into account along with the reconstruction of the city was an ingenious idea,” says Mr. Matsubayashi. He believes this viewpoint is needed as well in today’s urban redevelopment.

The Ten Views were renamed the “Places of Interest Related to the Atomic Bomb.” The renewed list included additional structures such as the A-bomb Dome and the stone steps where a human shadow was seared due to the bomb’s heat rays. These steps were located at the entrance of the Hiroshima Branch of the former Sumitomo Bank. Meanwhile, the items connected to the city government were removed from the list. In all, 13 things made up the Places of Interest.

Selecting and preserving these Places of Interest Related to the Atomic Bomb were promoted by an Australian national stationed in Hiroshima as a member of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces. He served as an advisor on the reconstruction of the city.

“Major Jarvie proposes preservation of A-bomb monuments,” was the headline for an article that appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun on July 8, 1948. Major Stanley Archibald Jarvie proposed that the city preserve these places, which would also promote tourism. The 1949 Shisei-yoran, a guide to the city’s administration, took the position, for the first time, that the “Hypocenter, Industrial Promotion Hall” and other places were “A-bomb monuments to be preserved.” This was the year that the Peace Memorial City Construction Law was enacted, providing the foundation for the reconstruction of the city.

Major Jarvie, who was a building engineer, also proposed a reconstruction plan for the city to address the war damage. Norioki Ishimaru, a professor at Hiroshima International University, has studied the plan and notes that Major Jarvie served as an advisor to the city from September 1947 to May 1949. “Mr. Jarvie must have proposed that the city preserve structures that were appealing from a Western point of view,” he said. “He was personally acquainted with Kenzo Tange, who was designing Peace Memorial Park around an axis that passed through the A-bomb Dome.”

These efforts to preserve A-bombed buildings, including the A-bomb Dome, which became a World Heritage site in 1996, began from the initial idea of the Ten Views. During the reconstruction process, most of the Ten Views disappeared, but some photos taken at around the time they were chosen have been found among the historical items stored at the Chugoku Shimbun. On the back of the photos are stamps of the Yukan Hiroshima Shimbun [Evning Hiroshima Newspaper], which was published by an affiliated company. For the first in 60 years, they can all be identified.

Having confirmed dates and places from the original prints, and conducted interviews, we would like to share these photographs with the public. Permission has been obtained, from family members of the late photographers, for their use. The Yukan Hiroshima Shimbun was launched in June 1946, becoming the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun in April 1950. The captions of the pictures are from the Chugoku Shimbun of August 11, 1947.

(Originally published on April 30, 2007)