Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Facing “that day,” doctor seeks traces of his army surgeon father

Aug. 6, 2020

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Takanobu Matsumoto, 74, a physician living in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, was born in August 1945, one week after his father, Kiyonori, an army surgeon, died in the atomic bombing. Mr. Matsumoto became a doctor, following in his father’s footsteps, but he had lived his life to that point without thinking much about his father or the atomic bombing, which had separated the father and son. However, 75 years after the bombing, Mr. Matsumoto began to fill what had become a “void” in his life by looking for traces of his father.

“Was my parents’ home around here?,” Mr. Matsumoto asked Atsuko Nishi, 84, an A-bomb survivor who lives in Nishi Ward. “My mother said she used to wave after my father when he left the house on horseback.” They were at the riverbank by Honkawa Elementary School in Naka Ward, from where the A-bomb Dome can be seen across the river. Ms. Nishi replied, “The Matsumoto family lived at that end.”

Chugoku Shimbun’s feature article served as impetus

Mr. Matsumoto and Ms. Nishi met because of an April Chugoku Shimbun feature article series that commemorated the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing: “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima—Recreating cityscapes.” Mr. Matsumoto’s parents used to live in the Kajiya-cho area (now Honkawa-cho, Naka Ward). After reading an article in which Ms. Nishi spoke about the Honkawa district before the atomic bombing, he contacted her wishing to know more about his father.

Kiyonori, the father, had entered Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) after studying at the former Hiroshima High School (now Hiroshima University). He returned to Hiroshima after graduation from the university’s faculty of medicine in 1942. On that day, August 6, 75 years ago, he experienced the atomic bombing at the Chugoku Military District Artillery Reserve near Hiroshima Castle. He was transported to a branch of the Hiroshima First Army Hospital in the area of Hesaka (now part of Higashi Ward), but died there one week later. He was 27 years old.

The following week, Mr. Matsumoto’s mother Mitsue, who died in 2008 at the age of 85, gave birth to Mr. Matsumoto in her hometown of Tokaichi-machi (now part of Miyoshi City). Her relatives did not inform her of Kiyonori’s death, simply explaining that he was very busy taking care of the injured. Mr. Matsumoto later learned that Mitsue, when told of the news, wandered along the train tracks with the baby, thinking about killing herself. On the first page of a collection of tanka poems (a 31-syllable Japanese poem) she published in 1977, Mitsue described the moment Kiyonori sent her off to her hometown for childbirth; her husband had said he was looking forward to her return home with a bouncing baby.

Mitsue remarried after the war, and Mr. Matsumoto was raised in the new family. He did not know about his real father until he reached around the age of 12. After then, Mr. Matsumoto recalled, Mitsue would often tell him about her memories with Kiyonori, but “I was not inclined to listen and her words went in one ear and out the other.”

Living up to his mother’s expectations, Mr. Matsumoto graduated from a medical school in Tokyo and obtained a medical license in 1972. After working for a time at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital and elsewhere, he opened a private clinic. In 1974, he married his wife, whose father was the late Heiichi Fujii, first secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). Mr. Matsumoto thus became familiar with the anti-nuclear movement, but he distanced himself from the father-in-law’s activities because of his mixed feelings that “while my father, grandmother, and aunt all died in the atomic bombing, some A-bomb victims are still alive.”

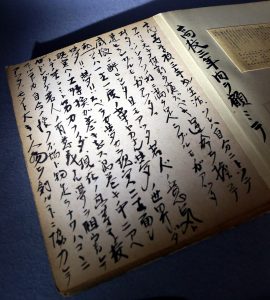

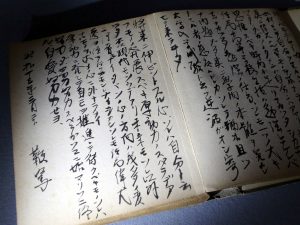

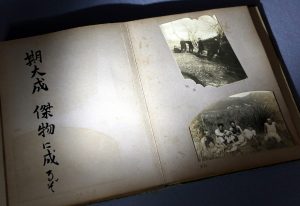

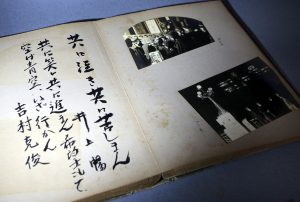

His thinking gradually changed as he grew older, and he started to go over the items that had been left by his parents. As he opens his father’s student yearbook of Hiroshima High School, a kanji character “YUME!” (“dream” in English) that his father seems to have written appears with other passionate messages. The words almost jump from the page, as if he can sense his father breathing. Mr. Matsumoto thought of his father’s regrets that his future was suddenly cut off. People who knew his father have already passed away. “Why didn’t I ask them earlier,” he wondered as his feelings of remorse continue to grow.

To donate data of his father’s student yearbook

“The feeling of anger

that the atomic bombing cannot be forgiven

remains the same

even after so long.”

Mr. Matsumoto believes that many bereaved families must have had the same feeling as his mother did when she wrote this tanka. He will soon donate the data of his father’s student yearbook to the Hiroshima University Archives.

(Originally published on August 6, 2020)

Ponders father’s regrets by looking at items left behind by his parents

Takanobu Matsumoto, 74, a physician living in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, was born in August 1945, one week after his father, Kiyonori, an army surgeon, died in the atomic bombing. Mr. Matsumoto became a doctor, following in his father’s footsteps, but he had lived his life to that point without thinking much about his father or the atomic bombing, which had separated the father and son. However, 75 years after the bombing, Mr. Matsumoto began to fill what had become a “void” in his life by looking for traces of his father.

“Was my parents’ home around here?,” Mr. Matsumoto asked Atsuko Nishi, 84, an A-bomb survivor who lives in Nishi Ward. “My mother said she used to wave after my father when he left the house on horseback.” They were at the riverbank by Honkawa Elementary School in Naka Ward, from where the A-bomb Dome can be seen across the river. Ms. Nishi replied, “The Matsumoto family lived at that end.”

Chugoku Shimbun’s feature article served as impetus

Mr. Matsumoto and Ms. Nishi met because of an April Chugoku Shimbun feature article series that commemorated the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing: “Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima—Recreating cityscapes.” Mr. Matsumoto’s parents used to live in the Kajiya-cho area (now Honkawa-cho, Naka Ward). After reading an article in which Ms. Nishi spoke about the Honkawa district before the atomic bombing, he contacted her wishing to know more about his father.

Kiyonori, the father, had entered Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) after studying at the former Hiroshima High School (now Hiroshima University). He returned to Hiroshima after graduation from the university’s faculty of medicine in 1942. On that day, August 6, 75 years ago, he experienced the atomic bombing at the Chugoku Military District Artillery Reserve near Hiroshima Castle. He was transported to a branch of the Hiroshima First Army Hospital in the area of Hesaka (now part of Higashi Ward), but died there one week later. He was 27 years old.

The following week, Mr. Matsumoto’s mother Mitsue, who died in 2008 at the age of 85, gave birth to Mr. Matsumoto in her hometown of Tokaichi-machi (now part of Miyoshi City). Her relatives did not inform her of Kiyonori’s death, simply explaining that he was very busy taking care of the injured. Mr. Matsumoto later learned that Mitsue, when told of the news, wandered along the train tracks with the baby, thinking about killing herself. On the first page of a collection of tanka poems (a 31-syllable Japanese poem) she published in 1977, Mitsue described the moment Kiyonori sent her off to her hometown for childbirth; her husband had said he was looking forward to her return home with a bouncing baby.

Mitsue remarried after the war, and Mr. Matsumoto was raised in the new family. He did not know about his real father until he reached around the age of 12. After then, Mr. Matsumoto recalled, Mitsue would often tell him about her memories with Kiyonori, but “I was not inclined to listen and her words went in one ear and out the other.”

Living up to his mother’s expectations, Mr. Matsumoto graduated from a medical school in Tokyo and obtained a medical license in 1972. After working for a time at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital and elsewhere, he opened a private clinic. In 1974, he married his wife, whose father was the late Heiichi Fujii, first secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo). Mr. Matsumoto thus became familiar with the anti-nuclear movement, but he distanced himself from the father-in-law’s activities because of his mixed feelings that “while my father, grandmother, and aunt all died in the atomic bombing, some A-bomb victims are still alive.”

His thinking gradually changed as he grew older, and he started to go over the items that had been left by his parents. As he opens his father’s student yearbook of Hiroshima High School, a kanji character “YUME!” (“dream” in English) that his father seems to have written appears with other passionate messages. The words almost jump from the page, as if he can sense his father breathing. Mr. Matsumoto thought of his father’s regrets that his future was suddenly cut off. People who knew his father have already passed away. “Why didn’t I ask them earlier,” he wondered as his feelings of remorse continue to grow.

To donate data of his father’s student yearbook

“The feeling of anger

that the atomic bombing cannot be forgiven

remains the same

even after so long.”

Mr. Matsumoto believes that many bereaved families must have had the same feeling as his mother did when she wrote this tanka. He will soon donate the data of his father’s student yearbook to the Hiroshima University Archives.

(Originally published on August 6, 2020)