Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Ms. Nakahara of Nishi Ward discovers aunt’s death in autopsy report on August 3

Aug. 6, 2020

by Kyoko Niiyama, Staff Writer

Satoe Nakahara, 76, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, had never heard from anyone in her family about how her aunt, Yayoi Nakahara, had died in the atomic bombing. Not knowing had always weighed on her mind. Earlier this month, Ms. Nakahara found the information in an autopsy report in the list of A-bomb victims made public by the city government. After 75 years, she finally filled the “void” that had remained about her aunt’s last moments. “She surely must have wanted to live longer,” Ms. Nakahara said, turning her thoughts to her relative of whom she has no recollection.

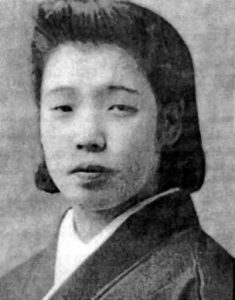

The Nakahara family lived in the Enkobashi-cho area near Hiroshima Station, in a house that used to also serve as the Tsukasaya Kimono Shop. Yayoi, 23 at the time, was the younger sister of Ms. Nakahara’s father, Seiji, and lived together with the family.

Yayoi was a teacher at Yasuda Girls’ High School. In the early morning on August 6, she left home never to return. The school building, located in the neighborhood of Nishihakushima-cho (now part of Naka Ward), about 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, was burned to the ground in the fires. Ms. Nakahara was one year old and at home with her mother, older brother, and grandparents when the bomb exploded. “My father never spoke of the atomic bombing, only telling me that my aunt had ‘died at her school’.” Although, Ms. Nakahara was young, she could sense her father’s sorrow.

After her older brother, Keiji, died last year, his name was added to the register of the A-bomb victims. That reminded Ms. Nakahara of her aunt Yayoi. She asked the city government and found that Yayoi did not appear in the register. She also found that the names of her mother and grandfather, who died several years after the atomic bombing, were also not in the records. The names of the three people were added to the register on August 6 last year.

She decided she wanted to find out more about Yayoi. As a last resort, on August 3, she thought to visit the International Conference Center Hiroshima, because the list of A-bomb victims was made available to the public until August 6. There, she found an autopsy report made out by the Higashi (East) Police Station. The report, dated September 5, 1945, explained that Yayoi had been burned to death in the clerk’s office of her school.

Ms. Nakahara visited Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School, which happens to be her alma mater, on August 5. She offered 23 origami cranes, as Yayoi was 23, to the monument for A-bomb victims at the school and put her hands together in prayer. Engraved on the monument’s stone marker are the names of 13 teachers, including Yayoi, and 311 students who were killed in the atomic bombing. “I have come to feel ever more acutely that her life was stolen by the bombing,” said Ms. Nakahara. The school holds a ceremony to console the souls of the victims in front of the stone marker on the morning of August 6.

(Originally published on August 6, 2020)

To console her aunt’s soul, visits location of her death in fires from atomic bombing when Nakahara was one year old

Satoe Nakahara, 76, a resident of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward, had never heard from anyone in her family about how her aunt, Yayoi Nakahara, had died in the atomic bombing. Not knowing had always weighed on her mind. Earlier this month, Ms. Nakahara found the information in an autopsy report in the list of A-bomb victims made public by the city government. After 75 years, she finally filled the “void” that had remained about her aunt’s last moments. “She surely must have wanted to live longer,” Ms. Nakahara said, turning her thoughts to her relative of whom she has no recollection.

The Nakahara family lived in the Enkobashi-cho area near Hiroshima Station, in a house that used to also serve as the Tsukasaya Kimono Shop. Yayoi, 23 at the time, was the younger sister of Ms. Nakahara’s father, Seiji, and lived together with the family.

Yayoi was a teacher at Yasuda Girls’ High School. In the early morning on August 6, she left home never to return. The school building, located in the neighborhood of Nishihakushima-cho (now part of Naka Ward), about 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, was burned to the ground in the fires. Ms. Nakahara was one year old and at home with her mother, older brother, and grandparents when the bomb exploded. “My father never spoke of the atomic bombing, only telling me that my aunt had ‘died at her school’.” Although, Ms. Nakahara was young, she could sense her father’s sorrow.

After her older brother, Keiji, died last year, his name was added to the register of the A-bomb victims. That reminded Ms. Nakahara of her aunt Yayoi. She asked the city government and found that Yayoi did not appear in the register. She also found that the names of her mother and grandfather, who died several years after the atomic bombing, were also not in the records. The names of the three people were added to the register on August 6 last year.

She decided she wanted to find out more about Yayoi. As a last resort, on August 3, she thought to visit the International Conference Center Hiroshima, because the list of A-bomb victims was made available to the public until August 6. There, she found an autopsy report made out by the Higashi (East) Police Station. The report, dated September 5, 1945, explained that Yayoi had been burned to death in the clerk’s office of her school.

Ms. Nakahara visited Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School, which happens to be her alma mater, on August 5. She offered 23 origami cranes, as Yayoi was 23, to the monument for A-bomb victims at the school and put her hands together in prayer. Engraved on the monument’s stone marker are the names of 13 teachers, including Yayoi, and 311 students who were killed in the atomic bombing. “I have come to feel ever more acutely that her life was stolen by the bombing,” said Ms. Nakahara. The school holds a ceremony to console the souls of the victims in front of the stone marker on the morning of August 6.

(Originally published on August 6, 2020)