Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Calling into question government’s obligations, Part 3: Peace Memorial Hall

May 21, 2020

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Enacted one year before the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law failed to incorporate individual compensation for each of the dead victims, which had been a strong demand of survivors’ organizations. Instead, its preamble and article 41 stipulated that the national government would keep in mind the sacrifice of the precious lives of those who perished in the atomic bombings.

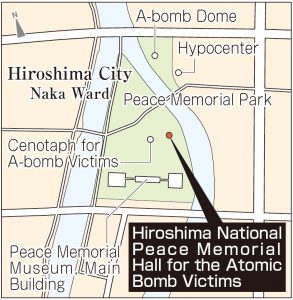

This stipulation materialized in the construction of the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, which opened in 2002 in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward). The memorial hall is managed by the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, an organization affiliated with the Hiroshima City government, based on a commission by the national government. The following year, a similar facility was established in Nagasaki.

Data on 23,789 people registered

Upon requests from victims’ relatives, the memorial hall registers in a computer database a variety of information about the deceased such as names, portraits, dates of death, and the circumstances in which the victims experienced the atomic bombing. The memorial hall’s data include portraits of those who died on August 6, 1945, in the period immediately following that date, and newly registered names of those who died recently. As of the end of March this year, the data of 23,789 people have been registered. Nevertheless, this is only a fraction of all the victims of the atomic bombing.

Visitors to the memorial hall can access data using computers, and by so doing, fully realize that every family of victims experienced hardship unique to each.

Masue Matsumoto, 78, a resident of Naka Ward, registered data about her uncle and his family 14 years ago, in the desire to “leave evidence of their lives.” Her uncle, Haruo Tsujiyama, then 32, ran a timepiece store in Hiroshima. All four members of the family—Mr. Tsujiyama, his wife Masuko, 30, brother Hikoji, 17, and father Tomokichi, 65—died in the atomic bombing.

Thanks to the efforts of Ms. Matsumoto, the Tsujiyama family was officially registered and thus avoided becoming another statistic in the “voids” of Hiroshima. We asked her whether the names were included in the city’s register of A-bomb victims placed beneath the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. Staring into space, she responded, “Come to think of it, I only made a request to the memorial hall.”

The Hiroshima City government began calling on people to provide information about A-bomb victims’ names to be registered in its records in May 1951, six years after the atomic bombing. Names have been added every year since then, and the register now has 319,186 names, which are kept confidential.

Since 1979, the city government has been trying to identify the names of victims using the register of the victims and other materials. As of the end of March 2019, 89,025 victims who had died by the end of 1945 were identified. But the estimated number of victims in that period is 140,000 plus or minus 10,000, meaning a gap still exists between the estimate and the actual number of identified victims. This situation also exists in Nagasaki, where 73,884 people are estimated to have died by the end of 1945, but only 32,054 have been identified.

Ms. Matsumoto inquired of the city government and found that the four people’s names had already been listed in the register. However, according to the city government, it does not use the data held by the memorial hall for its survey, and the two organizations do not share information, because “Most of the names are believed to be already included in the register of A-bomb victims.”

Is this the right approach? In reality, the register has “omissions.”

The father of Osamu Kamata, 75, a resident of Kyoto, died on August 6 in Hiroshima after he was called up for military service and assigned to work there. The Kyoto prefectural government’s department for support of war victims has a record of his death in the atomic bombing, but his name was not included in Hiroshima’s register. With that, last year, Mr. Kamata requested that his father’s name be registered.

Materials in different places throughout Japan

In addition to the information held by the memorial hall, there are many different materials including military records in the possession of prefectural governments. Making thorough use of such data, the voids in victims’ names can be minimized. The national government has always handed over reins to Hiroshima City regarding the survey on the entire picture of the number of atomic bomb victims. However, the government must become more involved in this effort in a responsible way.

Hiroshima’s atomic bombing victims include people from the Korean Peninsula, which was a colony of Japan in those days, and Japanese immigrants that had returned from the United States. After the war, many survivors emigrated from Japan. Among the 23,789 victims registered at the memorial hall, only 143 are from overseas, among which only 40 are from South Korea. It is clear that the national government has not invested sufficient effort in publicizing this project.

“The first step of ‘compensation’ is to record the existence of lives that were taken,” said Terumi Tanaka, 88, co-chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations. Mr. Tanaka, a resident of Niiza, Saitama Prefecture, regards the voids in records of the names of victims are the result of the national government’s “nonfeasance.” This fiscal year, he sits on an advisory committee that meets to discuss the memorial hall’s operations. He is determined to urge the national government to take appropriate action.

(Originally published on May 21, 2020)

Only fraction of victims’ names registered—Information also lacking for people overseas

Enacted one year before the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law failed to incorporate individual compensation for each of the dead victims, which had been a strong demand of survivors’ organizations. Instead, its preamble and article 41 stipulated that the national government would keep in mind the sacrifice of the precious lives of those who perished in the atomic bombings.

This stipulation materialized in the construction of the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, which opened in 2002 in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (Naka Ward). The memorial hall is managed by the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, an organization affiliated with the Hiroshima City government, based on a commission by the national government. The following year, a similar facility was established in Nagasaki.

Data on 23,789 people registered

Upon requests from victims’ relatives, the memorial hall registers in a computer database a variety of information about the deceased such as names, portraits, dates of death, and the circumstances in which the victims experienced the atomic bombing. The memorial hall’s data include portraits of those who died on August 6, 1945, in the period immediately following that date, and newly registered names of those who died recently. As of the end of March this year, the data of 23,789 people have been registered. Nevertheless, this is only a fraction of all the victims of the atomic bombing.

Visitors to the memorial hall can access data using computers, and by so doing, fully realize that every family of victims experienced hardship unique to each.

Masue Matsumoto, 78, a resident of Naka Ward, registered data about her uncle and his family 14 years ago, in the desire to “leave evidence of their lives.” Her uncle, Haruo Tsujiyama, then 32, ran a timepiece store in Hiroshima. All four members of the family—Mr. Tsujiyama, his wife Masuko, 30, brother Hikoji, 17, and father Tomokichi, 65—died in the atomic bombing.

Thanks to the efforts of Ms. Matsumoto, the Tsujiyama family was officially registered and thus avoided becoming another statistic in the “voids” of Hiroshima. We asked her whether the names were included in the city’s register of A-bomb victims placed beneath the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. Staring into space, she responded, “Come to think of it, I only made a request to the memorial hall.”

The Hiroshima City government began calling on people to provide information about A-bomb victims’ names to be registered in its records in May 1951, six years after the atomic bombing. Names have been added every year since then, and the register now has 319,186 names, which are kept confidential.

Since 1979, the city government has been trying to identify the names of victims using the register of the victims and other materials. As of the end of March 2019, 89,025 victims who had died by the end of 1945 were identified. But the estimated number of victims in that period is 140,000 plus or minus 10,000, meaning a gap still exists between the estimate and the actual number of identified victims. This situation also exists in Nagasaki, where 73,884 people are estimated to have died by the end of 1945, but only 32,054 have been identified.

Ms. Matsumoto inquired of the city government and found that the four people’s names had already been listed in the register. However, according to the city government, it does not use the data held by the memorial hall for its survey, and the two organizations do not share information, because “Most of the names are believed to be already included in the register of A-bomb victims.”

Is this the right approach? In reality, the register has “omissions.”

The father of Osamu Kamata, 75, a resident of Kyoto, died on August 6 in Hiroshima after he was called up for military service and assigned to work there. The Kyoto prefectural government’s department for support of war victims has a record of his death in the atomic bombing, but his name was not included in Hiroshima’s register. With that, last year, Mr. Kamata requested that his father’s name be registered.

Materials in different places throughout Japan

In addition to the information held by the memorial hall, there are many different materials including military records in the possession of prefectural governments. Making thorough use of such data, the voids in victims’ names can be minimized. The national government has always handed over reins to Hiroshima City regarding the survey on the entire picture of the number of atomic bomb victims. However, the government must become more involved in this effort in a responsible way.

Hiroshima’s atomic bombing victims include people from the Korean Peninsula, which was a colony of Japan in those days, and Japanese immigrants that had returned from the United States. After the war, many survivors emigrated from Japan. Among the 23,789 victims registered at the memorial hall, only 143 are from overseas, among which only 40 are from South Korea. It is clear that the national government has not invested sufficient effort in publicizing this project.

“The first step of ‘compensation’ is to record the existence of lives that were taken,” said Terumi Tanaka, 88, co-chair of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations. Mr. Tanaka, a resident of Niiza, Saitama Prefecture, regards the voids in records of the names of victims are the result of the national government’s “nonfeasance.” This fiscal year, he sits on an advisory committee that meets to discuss the memorial hall’s operations. He is determined to urge the national government to take appropriate action.

(Originally published on May 21, 2020)