Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Yamane family in Asakita Ward mark the day by transcending generational boundaries

Aug. 7, 2020

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

Seventy-five years ago, a boy’s seared lunchbox remained after a single atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima by the U.S. military. In July this year, his mother’s diary was discovered. She had frantically looked for her son after the bombing, but could only find his lunchbox. She brought it back home and died 10 years after the atomic bombing. Herein, the surviving family members reflect on the mother’s deep sorrow and the scars the atomic bombing left on the family’s history.

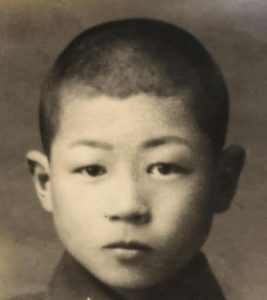

The lunchbox’s owner was Hideo Yamane, then 12 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. On August 6 this year, Yoshie Yamane, 86, Hideo’s younger sister who now lives in the town of Shiraki-machi in Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward, pointed to a road connecting her home to the nearest station, and said, “In the morning on that day, my brother walked down this road, looking back at us repeatedly.”

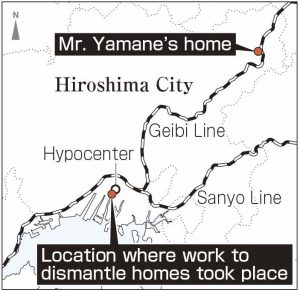

On that day 75 years ago, Hideo left home in Shiraki-machi ahead of schedule to participate in the dismantling of homes to create firebreaks in Nakajima-shinmachi (now part of Naka Ward). He never returned.

In a diary entry dated August 6, 1945, his mother wrote, “Every time a train arrived, I rushed to the station, but I couldn’t find Hideo.”

Hideo’s mother, Hatsue, who died at age 43 in 1955, left a diary chronicling events from August 5, 1945, until March 31, 1946. She used an invoice book from the sake brewing shop her family operated to keep the diary in place of a diary notebook. On August 7, as people wounded in the bombing were being transported by train after train on the Geibi Line, she found a second-year student from her son’s school on the train who told her that all first-year students in the school had perished. She immediately headed into the city of Hiroshima.

Day after day, Hatsue left home early in the morning to visit numerous aid stations and hospitals until it grew dark. She also traveled to outlying areas such as Ninoshima Island and Hatsukaichi in an attempt to find her son. If she was unable to buy a train ticket, she would dare to get on the train without one. In a diary entry dated August 7, she wrote, “Not a single clue has been found.” In an entry dated August 10, she mentioned, “I couldn’t find him on the fatalities list or among the surviving patients at the hospital.” In one dated August 11, she indicated, “I was unable to catch any sight of Hideo.” On August 12, she wrote, “His name wasn’t included on the list.”

On August 13, she found Hideo’s lunchbox amid the ruins. She discovered it while walking near the place where first-year students at his school were engaged in the demolition work, “because I wanted to remember the scene at the very least as a memory of my son,” according to her diary. She wrote, “I saw that Hideo’s lunchbox was stacked together with the Sako boy’s. I was drawn to it, picked it up, and checked inside.”

The edge of the lunchbox had been was torn and twisted, and charred food remained inside. That day, Hatsue had placed food such as fried egg and boiled spinach in the lunchbox. She wrote, “I could tell immediately it was his lunchbox,” by comparing it with other students’ lunchboxes primarily filled with millet. She brought it back home and placed it on her family altar.

In the diary, she also wrote of her sorrow from losing him, an emotion she felt increasingly acutely as time went on. From an entry dated November 13, she described it as, “Day by day, a distance seems to increase between my soul and his soul. I feel sad because it is like I am being left behind by him step by step.”

Yoshie said, “My mother used to cry almost every day.” Ten years after the atomic bombing, Hatsue developed lung disease and died. Yoshie still thinks her mother might have died from a disease related to the atomic bombing.

Yoshie took over possession of her brother’s lunchbox. Three years ago, she began to live with Yusuke Yamane, 35, her grandson. Based on his suggestion, last autumn she donated the lunchbox to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in the city’s Naka Ward.

All of Hatsue’s belongings are said to have been incinerated at the time of her death, probably due to the fear that her lung disease was infectious. But her diary was found by chance last month hidden among the accounting books at the shop. Thinking that Hatsue may have wanted others to read it, Yusuke and Yoshie decided to at least keep the diary at hand to serve as a family history.

In an entry dated November 13, 1945, Hatsue wrote, “Hideo, I recalled myself 13 years ago, full of hope as a mother breastfeeding you while lying on the bed. The memory made me so miserable.”

Yusuke’s first daughter was born in March this year. He will be able to witness firsthand the significance of that sentence in the diary. He said, “I now want to make August 6 a day to reflect on my family’s sorrow.” The memories of the atomic bombing passed down to victims’ families are a piece with which to fill the “voids” that remain in Hiroshima.

(Originally published on August 7, 2020)

With lunchbox of late brother and diary of mother who searched for son: “August 6 should be day to reflect on family’s sorrow”

Seventy-five years ago, a boy’s seared lunchbox remained after a single atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima by the U.S. military. In July this year, his mother’s diary was discovered. She had frantically looked for her son after the bombing, but could only find his lunchbox. She brought it back home and died 10 years after the atomic bombing. Herein, the surviving family members reflect on the mother’s deep sorrow and the scars the atomic bombing left on the family’s history.

The lunchbox’s owner was Hideo Yamane, then 12 and a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. On August 6 this year, Yoshie Yamane, 86, Hideo’s younger sister who now lives in the town of Shiraki-machi in Hiroshima’s Asakita Ward, pointed to a road connecting her home to the nearest station, and said, “In the morning on that day, my brother walked down this road, looking back at us repeatedly.”

On that day 75 years ago, Hideo left home in Shiraki-machi ahead of schedule to participate in the dismantling of homes to create firebreaks in Nakajima-shinmachi (now part of Naka Ward). He never returned.

In a diary entry dated August 6, 1945, his mother wrote, “Every time a train arrived, I rushed to the station, but I couldn’t find Hideo.”

Hideo’s mother, Hatsue, who died at age 43 in 1955, left a diary chronicling events from August 5, 1945, until March 31, 1946. She used an invoice book from the sake brewing shop her family operated to keep the diary in place of a diary notebook. On August 7, as people wounded in the bombing were being transported by train after train on the Geibi Line, she found a second-year student from her son’s school on the train who told her that all first-year students in the school had perished. She immediately headed into the city of Hiroshima.

Day after day, Hatsue left home early in the morning to visit numerous aid stations and hospitals until it grew dark. She also traveled to outlying areas such as Ninoshima Island and Hatsukaichi in an attempt to find her son. If she was unable to buy a train ticket, she would dare to get on the train without one. In a diary entry dated August 7, she wrote, “Not a single clue has been found.” In an entry dated August 10, she mentioned, “I couldn’t find him on the fatalities list or among the surviving patients at the hospital.” In one dated August 11, she indicated, “I was unable to catch any sight of Hideo.” On August 12, she wrote, “His name wasn’t included on the list.”

On August 13, she found Hideo’s lunchbox amid the ruins. She discovered it while walking near the place where first-year students at his school were engaged in the demolition work, “because I wanted to remember the scene at the very least as a memory of my son,” according to her diary. She wrote, “I saw that Hideo’s lunchbox was stacked together with the Sako boy’s. I was drawn to it, picked it up, and checked inside.”

The edge of the lunchbox had been was torn and twisted, and charred food remained inside. That day, Hatsue had placed food such as fried egg and boiled spinach in the lunchbox. She wrote, “I could tell immediately it was his lunchbox,” by comparing it with other students’ lunchboxes primarily filled with millet. She brought it back home and placed it on her family altar.

In the diary, she also wrote of her sorrow from losing him, an emotion she felt increasingly acutely as time went on. From an entry dated November 13, she described it as, “Day by day, a distance seems to increase between my soul and his soul. I feel sad because it is like I am being left behind by him step by step.”

Yoshie said, “My mother used to cry almost every day.” Ten years after the atomic bombing, Hatsue developed lung disease and died. Yoshie still thinks her mother might have died from a disease related to the atomic bombing.

Yoshie took over possession of her brother’s lunchbox. Three years ago, she began to live with Yusuke Yamane, 35, her grandson. Based on his suggestion, last autumn she donated the lunchbox to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in the city’s Naka Ward.

All of Hatsue’s belongings are said to have been incinerated at the time of her death, probably due to the fear that her lung disease was infectious. But her diary was found by chance last month hidden among the accounting books at the shop. Thinking that Hatsue may have wanted others to read it, Yusuke and Yoshie decided to at least keep the diary at hand to serve as a family history.

In an entry dated November 13, 1945, Hatsue wrote, “Hideo, I recalled myself 13 years ago, full of hope as a mother breastfeeding you while lying on the bed. The memory made me so miserable.”

Yusuke’s first daughter was born in March this year. He will be able to witness firsthand the significance of that sentence in the diary. He said, “I now want to make August 6 a day to reflect on my family’s sorrow.” The memories of the atomic bombing passed down to victims’ families are a piece with which to fill the “voids” that remain in Hiroshima.

(Originally published on August 7, 2020)