Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Calling into question government’s obligations, Part 8: Second-generation A-bomb survivors

May 29, 2020

by Minami Yamashita, Staff Writer

The atomic bombings have placed a heavy burden of health concerns and disease on the shoulders of A-bomb survivors throughout their lives. The bombings also exposed to radiation unborn fetuses that were in their mother’s womb. As of the end of March last year, 6,979 A-bomb survivors exposed to the bombing while in their mother’s womb held an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. At least 18 are survivors with A-bomb microcephaly (born with a reduced head size) and associated mental and physical disabilities. They were born to mothers exposed to high levels of radiation at an early stage of pregnancy.

One major reason for nuclear weapons, such as the atomic bombs, being called “the most inhumane weapon” is that they can inflict damage on people in subsequent generations who had nothing to do with the war in which the weapons were used. With that, what kind of damage was passed on to second-generation A-bomb survivors?

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), an organization located in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward and jointly operated by the United States and Japan, has continued studies into A-bomb survivors for more than 70 years since the time of its predecessor organization the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC). RERF also conducts studies into second-generation survivors, including mortality and incidence of certain diseases. According to the frequently-asked-questions page (FAQs) on RERF’s website, in terms of health effects observed in this group, “Thus far, no evidence of increased genetic effects has been found…but it will require several more decades to fully determine this, as this population is still relatively young.”

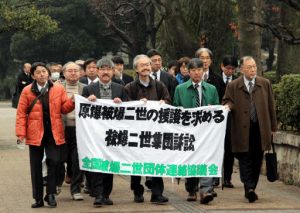

“Do we really have to live on without any resolution of our health concerns?” said Katsuhiro Hirano, 62, an elementary school teacher and resident of the city of Hatsukaichi. Mr. Hirano serves as secretary general of the National Association of Second-generation A-bomb Survivors, through which labor union members and others in Hiroshima and Nagasaki engage in related activities.

Mr. Hirano’s mother, Fukue, was exposed to radiation after entering the city in the aftermath of the atomic bombing when she was 20 years of age. Mr. Hirano was born 13 years later. He has been concerned about things that happened to those around him, including his cousin, who was also a second-generation survivor but died in his 30s. His mother lost two children to miscarriages during pregnancy before and after he was born. She revealed all this information to him just before she died in 2009.

Second-generation survivors live in such fear. ABCC, an organization established during the U.S. occupation of Japan in whose studies were reflected U.S. military intentions, was also interested in whether genetic effects were observed among the children of the survivors. From 1948 to 1954, ABCC conducted a study on about 77,000 newborns in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When a baby was stillborn or died immediately after birth, such cases were reported to ABCC by midwives. ABCC would come pick up the bodies and create organ samples and clinical records, which were sent to the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP).

Handled separately from aid provided to A-bomb survivors

Mr. Hirano’s association estimates there are about 300,000–500,000 second-generation A-bomb survivors nationwide in Japan. To respond to their concerns about health, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has had them undergo no-cost annual health checkups since fiscal 1979. However, the exams are simple checks involving blood and urine testing and a medical consultation. A multiple myeloma test was the only recent addition to the testing protocol. Moreover, the checkups are defined as a separate initiative from the provision of aid to A-bomb survivors.

Class-action lawsuit filed, based on claim that government’s treatment violated constitution

The association has demanded that the government conduct cancer and other tests for second-generation survivors, but the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has not granted approval for the tests, arguing “Health effects of bomb radiation to second-generation A-bomb survivors haven’t been scientifically confirmed.” In 2017, around 50 plaintiffs including Mr. Hirano filed a class-action lawsuit with Hiroshima District Court and Nagasaki District Court, claiming that the national government violated the constitution because it failed to provide aid to second-generation A-bomb survivors. Mr. Hirano said, “As long as the government is not able to firmly conclude there are no effects at all, it should provide assistance to second-generation survivors as part of its efforts to provide aid to A-bomb survivors.”

Depending on the region in Japan, a unique system is in place for second-generation survivors. In Tokyo, they are eligible to undergo free annual cancer testing, and if certain conditions are met, medical expenses they usually must pay out of pocket are covered. Similarly, Kanagawa Prefecture has provided assistance to cover their medical expenses for certain designated diseases.

Both the prefectural and municipal governments in the two A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have adopted a stance that assistance should be provided by the national Japanese government. Without preparing their own systems, these local governments request that the national government enhance the health-examination protocol.

Michiko Murata, 69, advisor for the Tokyo Federation of A-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Toyukai), said, “In principle, this is an issue that the national government should take responsibility for because it started the war. It is not acceptable that second-generation survivors are not treated equally depending on the area in which they live.” Toyukai is a Tokyo-based A-bomb survivors’ organization that has demanded the Tokyo metropolitan government develop measures for second-generation A-bomb survivors. She added that some of the survivors, afraid of discrimination, do not want the issue to become evident.

“Voids” still exist for second-generation survivors because no conclusion has been made on whether their health conditions were affected by exposure to A-bomb radiation. They have had to shoulder the persistent burden of health concerns from birth, but even still, fall outside the framework for aid from the national government. However, their feelings about the issue are not monolithic, and the conditions in which their parents were exposed to the atomic bombing are varied. To what extent will the national Japanese government meet the wishes of second-generation survivors? The government is being called into question on this issue, partly because its stance will reveal the government’s thinking about the issue of war damages.

(Originally published on May 29, 2020)

“Genetic effects” unproven, put second-generation outside scope of aid—But health concerns persist from birth

The atomic bombings have placed a heavy burden of health concerns and disease on the shoulders of A-bomb survivors throughout their lives. The bombings also exposed to radiation unborn fetuses that were in their mother’s womb. As of the end of March last year, 6,979 A-bomb survivors exposed to the bombing while in their mother’s womb held an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. At least 18 are survivors with A-bomb microcephaly (born with a reduced head size) and associated mental and physical disabilities. They were born to mothers exposed to high levels of radiation at an early stage of pregnancy.

One major reason for nuclear weapons, such as the atomic bombs, being called “the most inhumane weapon” is that they can inflict damage on people in subsequent generations who had nothing to do with the war in which the weapons were used. With that, what kind of damage was passed on to second-generation A-bomb survivors?

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), an organization located in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward and jointly operated by the United States and Japan, has continued studies into A-bomb survivors for more than 70 years since the time of its predecessor organization the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC). RERF also conducts studies into second-generation survivors, including mortality and incidence of certain diseases. According to the frequently-asked-questions page (FAQs) on RERF’s website, in terms of health effects observed in this group, “Thus far, no evidence of increased genetic effects has been found…but it will require several more decades to fully determine this, as this population is still relatively young.”

“Do we really have to live on without any resolution of our health concerns?” said Katsuhiro Hirano, 62, an elementary school teacher and resident of the city of Hatsukaichi. Mr. Hirano serves as secretary general of the National Association of Second-generation A-bomb Survivors, through which labor union members and others in Hiroshima and Nagasaki engage in related activities.

Mr. Hirano’s mother, Fukue, was exposed to radiation after entering the city in the aftermath of the atomic bombing when she was 20 years of age. Mr. Hirano was born 13 years later. He has been concerned about things that happened to those around him, including his cousin, who was also a second-generation survivor but died in his 30s. His mother lost two children to miscarriages during pregnancy before and after he was born. She revealed all this information to him just before she died in 2009.

Second-generation survivors live in such fear. ABCC, an organization established during the U.S. occupation of Japan in whose studies were reflected U.S. military intentions, was also interested in whether genetic effects were observed among the children of the survivors. From 1948 to 1954, ABCC conducted a study on about 77,000 newborns in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When a baby was stillborn or died immediately after birth, such cases were reported to ABCC by midwives. ABCC would come pick up the bodies and create organ samples and clinical records, which were sent to the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP).

Handled separately from aid provided to A-bomb survivors

Mr. Hirano’s association estimates there are about 300,000–500,000 second-generation A-bomb survivors nationwide in Japan. To respond to their concerns about health, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has had them undergo no-cost annual health checkups since fiscal 1979. However, the exams are simple checks involving blood and urine testing and a medical consultation. A multiple myeloma test was the only recent addition to the testing protocol. Moreover, the checkups are defined as a separate initiative from the provision of aid to A-bomb survivors.

Class-action lawsuit filed, based on claim that government’s treatment violated constitution

The association has demanded that the government conduct cancer and other tests for second-generation survivors, but the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has not granted approval for the tests, arguing “Health effects of bomb radiation to second-generation A-bomb survivors haven’t been scientifically confirmed.” In 2017, around 50 plaintiffs including Mr. Hirano filed a class-action lawsuit with Hiroshima District Court and Nagasaki District Court, claiming that the national government violated the constitution because it failed to provide aid to second-generation A-bomb survivors. Mr. Hirano said, “As long as the government is not able to firmly conclude there are no effects at all, it should provide assistance to second-generation survivors as part of its efforts to provide aid to A-bomb survivors.”

Depending on the region in Japan, a unique system is in place for second-generation survivors. In Tokyo, they are eligible to undergo free annual cancer testing, and if certain conditions are met, medical expenses they usually must pay out of pocket are covered. Similarly, Kanagawa Prefecture has provided assistance to cover their medical expenses for certain designated diseases.

Both the prefectural and municipal governments in the two A-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have adopted a stance that assistance should be provided by the national Japanese government. Without preparing their own systems, these local governments request that the national government enhance the health-examination protocol.

Michiko Murata, 69, advisor for the Tokyo Federation of A-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Toyukai), said, “In principle, this is an issue that the national government should take responsibility for because it started the war. It is not acceptable that second-generation survivors are not treated equally depending on the area in which they live.” Toyukai is a Tokyo-based A-bomb survivors’ organization that has demanded the Tokyo metropolitan government develop measures for second-generation A-bomb survivors. She added that some of the survivors, afraid of discrimination, do not want the issue to become evident.

“Voids” still exist for second-generation survivors because no conclusion has been made on whether their health conditions were affected by exposure to A-bomb radiation. They have had to shoulder the persistent burden of health concerns from birth, but even still, fall outside the framework for aid from the national government. However, their feelings about the issue are not monolithic, and the conditions in which their parents were exposed to the atomic bombing are varied. To what extent will the national Japanese government meet the wishes of second-generation survivors? The government is being called into question on this issue, partly because its stance will reveal the government’s thinking about the issue of war damages.

(Originally published on May 29, 2020)