Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing—Records of First Girls’ School mobilized students, Part 4: Passing on materials to later generations

Jul. 26, 2021

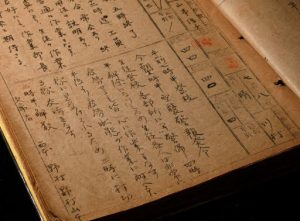

There are few opportunities to access most of the World War II documents from the Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School (First Girls’ School) that are archived at Funairi High School, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward. Some of the materials have been utilized in exhibits or research. In the summer of last year, a graduate of Funairi High School tackled work related to two volumes of records involving the mobilization of students.

Sayaka Aoyama, 23, a resident of Naka Ward, began work at the Hiroshima Prefectural government earlier this year in the spring. At the Faculty of Law and Literature of Shimane University, the school she entered upon graduation from the high school, she wrote a graduation thesis about mobilized female students in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. Ms. Aoyama said, “I wanted to do research not only about the fact that female students were killed in the atomic bombing, but also about how they lived during wartime by incorporating stories of survivors.”

Records used in academic research

Ms. Aoyama took close-up photographs of the records at her alma mater and spent six months carefully poring over the materials, while also researching wartime laws and regulations, the former education system used in Japan, and terms she did not clearly understand. She finished her 138-page thesis by cross-checking the records against a publication titled “Ryuto” (floating lanterns, in English), which comprises a collection of essays published in 1957 by the bereaved families of First Girls’ School victims, and the testimonies of Yachiyo Kato, 92, an A-bomb survivor who had been a student at First Girls’ School.

Between the air raid warnings issued frequently, First Girls’ School students participated in work at certain factories. Reading the records, Ms. Aoyama was saddened because she imagined how hard they must have worked. At the same time, she became aware that the supervising teachers made an effort to take care of the students, and that the students enjoyed leisure activities in their free time such as going to movies or reading books. Her imagination was inspired by not only the texts in the records but also by their paper quality, smell, brushstrokes, and phrasings. “I thought the First Girls’ School students were just like us. As the records consisted of original material, I was able to ultimately feel familiarity with them,” said Ms. Aoyama.

How were these documents preserved? Recently, someone related to the school’s alumni association contacted the Chugoku Shimbun, informing us that, “There is a statement that can provide a clue to the materials that appears in a publication commemorating the 60th anniversary of the association’s foundation.”

The publication from 40 years ago ran a narrative written by a male clerk at the school who had created a list of A-bomb victims from First Girls’ School in 1952. He wrote, “I had no knowledge of female students being mobilized to work at factories or to dismantle buildings.” He wrote that he had picked out documents kept at the warehouse on the school’s grounds that he thought would be of help in preparing the list and brought them to his office. One day, the principal ordered him to discard the materials, but he was determined to hide them in the warehouse, after hesitating about whether it would be appropriate to discard such valuable items.

Later, when the alumni association published “Ryuto” in 1977, some of the documents were reprinted in the publication. Except for that instance, materials from First Girls’ School remained packed up in cardboard boxes.

Hideyuki Sato, 77, one of the school’s former teachers who lives in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward, recalled the shock he experienced when he discovered boxes containing old materials in the document storeroom in 1984 and opened them casually. Mr. Sato found many columns indicating “Dead” had been checked off on the student survey chart, which described the whereabouts of first- and second-year students who had been mobilized to join the demolition of buildings to create fire lanes for the war effort. “I became emotional when imagining what it would have been like had I had been their teacher.” He had members of the school’s social-issues study club, for which he served as advisor, transcribe the records and other documents, and at a school festival the club made a presentation of what was found in the materials.

School senses limitations about continued preservation

When the old school building was replaced with the current structure in 1998, the documents in cardboard boxes were not discarded but instead moved to the newly constructed building. Most have been kept on shelves in the principal’s office. Other materials such as accounts of the aftermath of the atomic bombing and parts of student mobilization records have been archived in the so-called “First Girls’ School section,” a secure area newly established in the school’s library.

Teachers are often transferred to other schools every few years. It seems no specific system is in place to handle the passing on of information about the First Girls’ School materials. Yohei Mito, 58, vice principal of present-day Funairi High School, said, “Some students have expressed their interest in viewing the documents. We want to keep them close at hand, but we also feel there is a limit to their continued storage at the school.” Based on discussions with the alumni association and Hiroshima City’s Board of Education, the school will consider options for preservation, such as depositing the entirety of materials with a public organization.

Historical materials that exceed the level of practical work documents within the organization must exist somewhere in addition to the school. The significance of such materials for gaining better understanding of the past would be enhanced only when all original materials are archived together. Measures to ensure that such materials are passed on to following generations certainly seem warranted.

(Originally published on July 23, 2021)