Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 5)

May 1, 2012

Printing in Nukushina

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

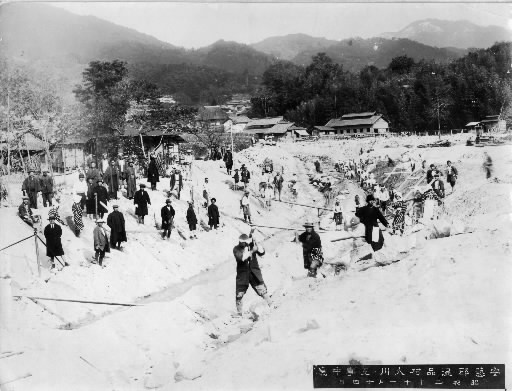

Employees gather in location where press had been taken

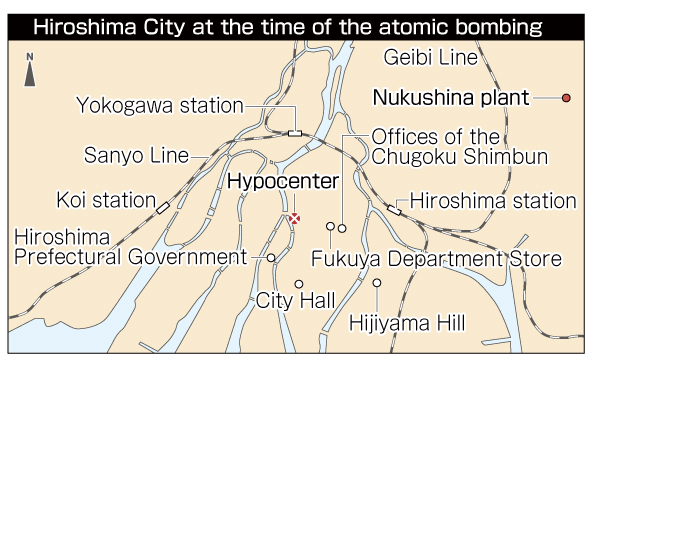

The offices of the Chugoku Shimbun were completely destroyed by fire on August 6, 1945. Despite losing family members and suffering from the acute effects of radiation, the employees who had escaped death in the atomic bombing commuted to work in Nukushina (Higashi Ward), a village nestled among the hills on the outskirts of the city, where a rotary press had been taken. Amid the disruption of power transmission, communication and other functions of the city, the employees worked to resume publication of the paper printed by the Chugoku Shimbun itself. The newspaper of A-bombed Hiroshima was launched at the plant relocated to Nukushina.

Despite injuries from A-bombing, employees resume publication

Just after the end of the war Hisako Nakano (née Kakui), 84, noticed a copy of the Chugoku Shimbun taped to the wall of the railway station in Itsukaichi on the outskirts of the city. She had been at her home in Kusunoki-cho (Nishi Ward) at the time of the A-bombing and was traveling back and forth between there and her uncle’s home in Yawata (Saeki Ward), where she was staying.

“I was surprised to see that the paper was out,” she said.

The paper had continued to be printed by the Asahi and Mainichi papers, but when Ms. Nakano, who was a typesetter for the paper, saw the masthead of the Chugoku Shimbun featuring the gateway to the shrine at Miyajima, she was overcome by “an indescribable feeling.”

The day after she saw the paper she walked through the ruins of the city to Kami-nagarakewa-cho (now Ebisu-cho, Naka Ward), the site of the newspaper’s offices. “I saw a notice written on a tree or a paper saying, ‘All those who can go to work, please come by 9 a.m. tomorrow.’ So the next day I went to work at the usual time.”

A three-wheeled motorbike came along and picked up four or five people who had gathered in front of the paper’s offices. The vehicle traveled the rough road over the Ouchigoe Pass and arrived at a dairy farm in Nukushina. The rotary press was in the cowshed.

Two presses destroyed by fire

Power transmission difficult

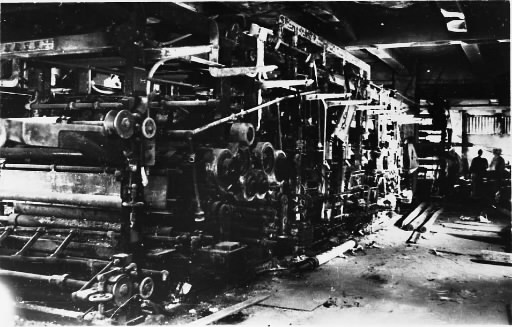

In July Jitsuichi Yamamoto, then 55 and president of the Chugoku Shimbun, had decided that one rotary printing press should be relocated for safekeeping and selected the Kawate farm in Nukushina as the location. “After all, the printing presses are a newspaper’s lifeline. If they are burned, we can’t do a thing,” he said.

Hisato Ishikawa, then 31 and assistant manager of the printing department, later described the process, which entailed disassembling the press, transporting it by horse cart and reassembling it at the dairy farm, in an essay included in a book compiled in 1958 in memory of Mr. Yamamoto.

“We finished assembling the press on August 2. It was ready for a trial run if electricity could be supplied to it,” Mr. Ishikawa wrote. Typecasting equipment and other necessary materials were also moved to Nukushina.

The two rotary presses at the paper’s downtown offices were destroyed by fire in the A-bombing, so the press that had been taken to Nukushina would be the Chugoku Shimbun’s lifeline to resuming publication on its own.

On August 21 Hiroshima Prefecture sent a highly confidential memo to the Ministry of the Interior and other agencies “regarding the matter of damage from the August 6 air raid on Hiroshima and measures being taken.” A copy of the memo is held in the prefecture’s archives. It describes the difficult circumstances the Nukushina plant was in. The plant was a temporary facility in the hills, and the power transmission problem affected operation of the press.

“A high-speed rotary press and associated equipment have been relocated to Nukushina, Aki-gun, which is under the prefecture’s jurisdiction,” the memo said. “The paper plans to resume printing within a day or two, but it is believed that it will be difficult to return to the pre-disaster level with the current capacity.”

The surviving employees of the main office of Chugoku Haiden (now the Chugoku Electric Power Co.) and employees hired to deal with the emergency worked with members of the Imperial Army Marine Transport Unit to put half-burned power poles back up and to string the burned power lines. By August 20 power distribution equipment had been restored for “30 percent of the houses still standing” in the area more than 2 km away from the hypocenter.

According to Volume 3 of the “Record of the A-Bomb Disaster” issued by the City of Hiroshima in 1971, a high-voltage power distribution line to the Nukushina plant was “finished around the 11th.” But “there was a series of problems with materials for construction and wiring at the plant,” and power transmission had still not resumed at the end of the war.

Plus employees were stricken by the acute effects of radiation. Yasuo Yamamoto, then 42 and manager of the paper’s stenographic department, was at the Nukushina plant when he heard the news that the war had ended. He recalled that time in the August 1965 edition of “Shinju,” an anthology of poetry he edited. He was bicycling to work from his home in Danbaranaka-machi (now Danbaraminami, Minami Ward) when he was exposed to the A-bombing.

“After 20 days my hair began to fall out in the places where I had been burned… But I couldn’t take a day off from our preparations to put out the paper, so I continued to make that long-distance round trip by bicycle with my white bandages on.”

He continued, “Some of those who had been lucky enough to escape harm began to come back to work and then got leukemia and died. I was depressed and wondered if we’d really be able to put out the paper there.”

Ms. Nakano recalled one person who was felled by the effects of radiation. “When I got to Nukushina, I saw Noboru Tanabe. He was happy to see me and said he was glad we’d both survived, but then he died.” Mr. Tanabe, then 48, was assistant manager of the typesetting department. Ms. Nakano recalled him as “a good-natured man.” He died on August 29.

Fifteen employees sleep in tents

There were tents at the Nukushina plant where employees who had lost their homes in the A-bombing slept. The Chugoku Shimbun has no photographs taken at that time. The extent of the chaos that continued in the aftermath of the A-bombing can be surmised from this lack of photographs.

There are now many houses in Nukushina, but with the name “Kawate dairy farm” as a lead, the home of Takeshi Kawate, 70, was located in Nukushina 8-chome. It is situated on a portion of the land once occupied by the farm. “The farm was started by my grandfather, Sasaichi. There were 100 dairy cows, but there was a shortage of feed during the war, so operations were suspended and he loaned the land to the newspaper company, I was told.”

One of those who slept in the tents at the plant was also located. Hidefumi Sumida, 83, returned to Hiroshima in late August from the Army Air Communications School, which was located in Kakogawa, Hyogo Prefecture. There was nothing left of his family home in Sumiyoshi-cho (Naka Ward), and his sister, Tomiko, then 19 and a teacher at the Tenma National School, had died on August 11. He went to the newspaper offices in search of his mother, Kimiko, then 38. His father had died of illness before the war, and his mother worked in the advertising department of the Chugoku Shimbun.

“I was told my mother was alive and that she was in Nukushina, so I got a ride on a three-wheeled motorbike. I think we put the tents up along the riverbank. I had no home, and my mother was there. Since I was staying there, I started helping with the work.” He was hired by the Chugoku Shimbun on September 7. Around 15 people lived in tents, he said.

Rice and vegetables were delivered from the paper’s Miyoshi bureau, located in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, and Kimiko and others prepared meals. Mr. Sumida took bottles of milk to Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda) in Fuchu-cho. According to the Chronicle of A-bomb Damage to the Hiroshima Prefectural Government Offices published in 1976, on August 20 prefectural offices relocated to the premises of Toyo Kogyo. They were followed by the courthouse, district attorney’s office, the Chugoku Shimbun and other organizations. The Chugoku Shimbun established its editorial and general affairs departments there.

“Even a novice could tell that the rotary press wasn’t working right,” Mr. Sumida said. Because of the power shortage, the press ran slowly. The typecasting equipment didn’t work well either, and after they set an article in type, instead of melting it down afterwards as they would have ordinarily done, Ms. Nakano and the other typesetters put each letter back in the case. A cave-like air raid shelter next to the dairy farm served as the darkroom.

Appeal of the war-ravaged area

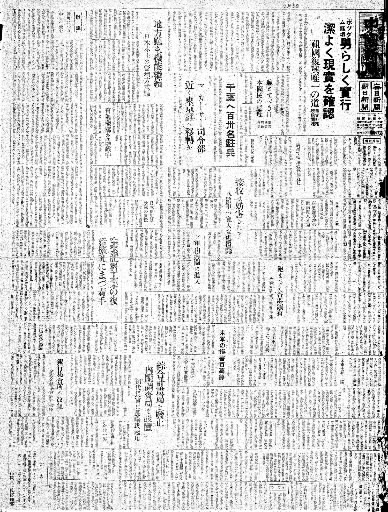

Through trial and error and the all-out efforts of the employees, printing of the paper by the Chugoku Shimbun resumed. The papers, which have been preserved on microfilm, began with the September 3 issue.

On September 2, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, and representatives of eight other Allied nations signed Japan’s instrument of surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay along with Mamoru Shigemitsu, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and other representatives of Japan.

At the top of the front page was Shigemitsu’s policy statement written as he prepared to sign the surrender. The article was distributed by the Domei News Agency. After the offices of the Chugoku Shimbun were destroyed by fire, the news agency moved its Hiroshima bureau to Gion-cho in Asa-gun (now Asa Minami Ward), where the Hara Studio of Hiroshima Central Broadcasting (later NHK) was located, according to the August 1967 edition of the bulletin of the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association.

In the upper left corner was the first appeal from A-bombed Hiroshima, an editorial with the headline “Request to central government concerning ravages of war.”

“The devastation of Hiroshima as a result of the attack by the atomic bomb is truly beyond description. It is a scene that indeed brought to mind the end of the world. We hope the authorities will immediately implement further aggressive and specific relief measures for the citizens of Hiroshima,” it said.

On September 2, the day printing began at the Nukushina plant, Akira Yamamoto, son of the paper’s president, returned home from Chiba Prefecture after being demobilized. Mr. Yamamoto, then 26, had been drafted into the navy in 1944.

According to his wife, Nobuko, now 88, after getting off the train at Hiroshima Station, Mr. Yamamoto walked through the ruins of the city to the site of the newspaper offices. After seeing that they had been destroyed, he headed to his parents’ home in Fuchu-cho.

Jitsuichi Yamamoto, the company president, had lost his elder son Toru, then 29, to the A-bombing. “I’m so glad you’re back,” he said through tears as the two men clasped each other’s hands. “Now I have the strength to go on living.”

Mr. Sumida recalled that Akira Yamamoto, who later became president of the paper, traveled to the plant in Nukushina and Toyo Kogyo astride the back of the sidecar of a motorbike wearing his navy uniform. An article Mr. Yamamoto wrote at that time was published in the October 2, 1945 edition of the news bulletin of the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association. A copy is stored in the association’s archives.

“Two tents stood proudly in a corner of the cows’ exercise area. The tents leaked terribly, and old corrugated tinplate taken from the burned-out city had been place on top. It may not have been good for us to sleep on the ground, but everyone was full of energy, tremendous energy.”

The people who went to work at the Nukushina plant got themselves going and worked to put the paper out. Thus reports from A-bombed Hiroshima began to be filed.

(Originally published on April 21, 2012)

Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 6)