Further steps toward a world without nuclear weapons in 2014

Jan. 16, 2014

by Yumi Kanazaki, Editorial Writer

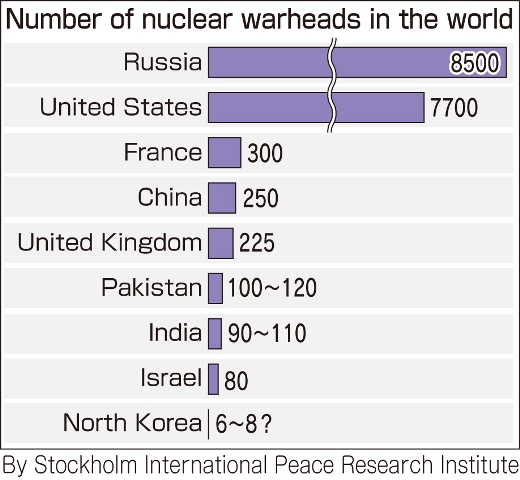

There are an estimated 17,265 nuclear warheads in the world today. These are weapons of mass destruction. Last year, for the first time, the Japanese government endorsed a joint statement on the humanitarian impact and non-use of nuclear weapons. At the same time, however, Japan is strengthening its military alliance with the world’s nuclear superpower, the United States. Relations between nations in East Asia have grown chilly as China adds to its arsenal of nuclear weapons and North Korea pushes ahead with its nuclear testing. This April, the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI) will hold a meeting of foreign ministers in Hiroshima, and the Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference meets in New York. The A-bombed cities and their citizens, as well as the Japanese government, must embrace feasible ideas and take initiative to advance a world without nuclear weapons.

A crucial stage to promote action beyond borders

Five nuclear weapons states, among them the United States and Russia, are commending themselves for small reductions in their nuclear stockpiles, claiming that they are meeting their obligations with regard to nuclear disarmament. But the non-nuclear-weapon states are impatient at their slow progress. When I reported on the 2010 Review Conference from New York, there was a stream of criticism from international NGOs, arguing that no progress would be made by relying on the NPT.

One phrase in the final document produced by the 2010 Review Conference, however, attracted wide attention and has led to growing momentum for nuclear disarmament, spearheaded by non-nuclear-weapon states and civil society.

Nuclear weapons are often discussed from a military perspective, but the final document considers the “catastrophic humanitarian consequences” of the use of nuclear arms. This approach isn’t new, but the renewed interest in weighing nuclear weapons from the viewpoint of international humanitarian law makes some nations feel that this development could lead to a nuclear weapons convention, an aspiration shared by the A-bombed cities.

And how about the Japanese government? Japan supported the joint statement on nuclear weapons that was issued at the United Nations last year, the fourth such statement and the first statement Japan has backed. The efforts of A-bomb survivors’ organizations and peace groups in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the presence of Mayors for Peace, led by the two cities, finally moved the mountain.

However, as long as Japan depends on the U.S. nuclear arsenal for its security, despite the government’s admission of the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, this nation will continue to oppose an outright ban. How can the A-bombed cities pursue dialogue with the Japanese government and persuade it to change the nation’s security policy? The international community, seeking nuclear disarmament, watches soberly.

The international conference held last March in Oslo, organized by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was attended by government officials and NGOs from roughly 130 nations. The event, which focused on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons by detailing the range of damage they would produce if used, also served as a symbol of this recent, rising trend.

The experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki convey the enormity of the destruction that atomic bombs wreak on human lives, lasting damage that still reverberates today. How can Hiroshima and Nagasaki become a more active part of the international community to increase this momentum for the abolition of nuclear weapons?

We must not lose this precious window of opportunity. In February, an international conference will be held in Mexico, following up on the Oslo gathering. The voices of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should be delivered directly and indirectly to support the work of the conference.

The NPDI is a unique multilateral initiative to promote nuclear disarmament, led by Australia and Japan, which relies on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, and supported by Mexico, Chile, and other nations that backed the U.N. joint statement. The discussions at the follow-up conference in Mexico, the NPDI foreign ministerial meeting held in Hiroshima in April, and the NPT PrepCom, which meets right after the NPDI meeting, will all affect the deliberations at the 2015 Review Conference.

We not only need to keep a spotlight on the inhumanity of nuclear arms, we must continue looking beyond this, too. In spite of expected opposition from nations that possess nuclear weapons, we must listen to the experiences of the A-bomb survivors and collaborate with like-minded people in the public and private sectors both in Japan and abroad. These are efforts not intended to overturn the NPT regime. 2014 will be an important year as we approach the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings in 2015.

Keywords

Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI)

The NPDI was launched by Japan and Australia in 2010 to generate proposals for maintaining and strengthening the NPT framework. Initially, the NPDI was comprised of 10 nations including Canada, Germany, and Mexico. With the addition of the Philippines and Nigeria in 2013, it now consists of 12 nations. The NPDI has held seven meetings of foreign ministers. This year’s meeting, to be held in Japan for the first time, will take place on April 12 in Hiroshima. The foreign ministers will also exchange views with A-bomb survivors.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

The NPT took effect in 1970 and was extended indefinitely in 1995. The number of member states is currently 190. The treaty permits the possession of nuclear weapons by the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China, while imposing on them the obligation to pursue negotiations for nuclear disarmament. The treaty grants non-nuclear-weapon states, including Japan, which ratified the treaty in 1976, the right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy. There have been controversies over the monopolization of nuclear weapons by the five nuclear powers and the potential risk of nuclear proliferation. India, Pakistan, and Israel, which are de facto nuclear weapon states, have not joined the treaty. North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003. An NPT Review Conference is held every five years to assess the implementation of the treaty. The PrepCom meeting for the next Review Conference will open on April 28 in New York.

(Originally published on January 1, 2014)

There are an estimated 17,265 nuclear warheads in the world today. These are weapons of mass destruction. Last year, for the first time, the Japanese government endorsed a joint statement on the humanitarian impact and non-use of nuclear weapons. At the same time, however, Japan is strengthening its military alliance with the world’s nuclear superpower, the United States. Relations between nations in East Asia have grown chilly as China adds to its arsenal of nuclear weapons and North Korea pushes ahead with its nuclear testing. This April, the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI) will hold a meeting of foreign ministers in Hiroshima, and the Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference meets in New York. The A-bombed cities and their citizens, as well as the Japanese government, must embrace feasible ideas and take initiative to advance a world without nuclear weapons.

A crucial stage to promote action beyond borders

Five nuclear weapons states, among them the United States and Russia, are commending themselves for small reductions in their nuclear stockpiles, claiming that they are meeting their obligations with regard to nuclear disarmament. But the non-nuclear-weapon states are impatient at their slow progress. When I reported on the 2010 Review Conference from New York, there was a stream of criticism from international NGOs, arguing that no progress would be made by relying on the NPT.

One phrase in the final document produced by the 2010 Review Conference, however, attracted wide attention and has led to growing momentum for nuclear disarmament, spearheaded by non-nuclear-weapon states and civil society.

Nuclear weapons are often discussed from a military perspective, but the final document considers the “catastrophic humanitarian consequences” of the use of nuclear arms. This approach isn’t new, but the renewed interest in weighing nuclear weapons from the viewpoint of international humanitarian law makes some nations feel that this development could lead to a nuclear weapons convention, an aspiration shared by the A-bombed cities.

And how about the Japanese government? Japan supported the joint statement on nuclear weapons that was issued at the United Nations last year, the fourth such statement and the first statement Japan has backed. The efforts of A-bomb survivors’ organizations and peace groups in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the presence of Mayors for Peace, led by the two cities, finally moved the mountain.

However, as long as Japan depends on the U.S. nuclear arsenal for its security, despite the government’s admission of the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, this nation will continue to oppose an outright ban. How can the A-bombed cities pursue dialogue with the Japanese government and persuade it to change the nation’s security policy? The international community, seeking nuclear disarmament, watches soberly.

The international conference held last March in Oslo, organized by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was attended by government officials and NGOs from roughly 130 nations. The event, which focused on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons by detailing the range of damage they would produce if used, also served as a symbol of this recent, rising trend.

The experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki convey the enormity of the destruction that atomic bombs wreak on human lives, lasting damage that still reverberates today. How can Hiroshima and Nagasaki become a more active part of the international community to increase this momentum for the abolition of nuclear weapons?

We must not lose this precious window of opportunity. In February, an international conference will be held in Mexico, following up on the Oslo gathering. The voices of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should be delivered directly and indirectly to support the work of the conference.

The NPDI is a unique multilateral initiative to promote nuclear disarmament, led by Australia and Japan, which relies on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, and supported by Mexico, Chile, and other nations that backed the U.N. joint statement. The discussions at the follow-up conference in Mexico, the NPDI foreign ministerial meeting held in Hiroshima in April, and the NPT PrepCom, which meets right after the NPDI meeting, will all affect the deliberations at the 2015 Review Conference.

We not only need to keep a spotlight on the inhumanity of nuclear arms, we must continue looking beyond this, too. In spite of expected opposition from nations that possess nuclear weapons, we must listen to the experiences of the A-bomb survivors and collaborate with like-minded people in the public and private sectors both in Japan and abroad. These are efforts not intended to overturn the NPT regime. 2014 will be an important year as we approach the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings in 2015.

Keywords

Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI)

The NPDI was launched by Japan and Australia in 2010 to generate proposals for maintaining and strengthening the NPT framework. Initially, the NPDI was comprised of 10 nations including Canada, Germany, and Mexico. With the addition of the Philippines and Nigeria in 2013, it now consists of 12 nations. The NPDI has held seven meetings of foreign ministers. This year’s meeting, to be held in Japan for the first time, will take place on April 12 in Hiroshima. The foreign ministers will also exchange views with A-bomb survivors.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

The NPT took effect in 1970 and was extended indefinitely in 1995. The number of member states is currently 190. The treaty permits the possession of nuclear weapons by the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China, while imposing on them the obligation to pursue negotiations for nuclear disarmament. The treaty grants non-nuclear-weapon states, including Japan, which ratified the treaty in 1976, the right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy. There have been controversies over the monopolization of nuclear weapons by the five nuclear powers and the potential risk of nuclear proliferation. India, Pakistan, and Israel, which are de facto nuclear weapon states, have not joined the treaty. North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003. An NPT Review Conference is held every five years to assess the implementation of the treaty. The PrepCom meeting for the next Review Conference will open on April 28 in New York.

(Originally published on January 1, 2014)