Special Series: 60 Years of RERF, Part III [1]

Sep. 8, 2014

Hiroshima and the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission: Unfulfilled research

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

This feature series on the past and future of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) originally began to appear in the Chugoku Shimbun in June 2007.

In 1947, two years after the atomic bombing, the United States established the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) in Hiroshima. More than a few A-bomb survivors and family members of the dead still harbor feelings of bitterness toward the ABCC, believing that the organization treated the survivors as mere subjects of research. What was the motive of the United States in forming this organization? What exactly did the ABCC, the forerunner of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), study in Hiroshima? The Chugoku Shimbun explores the true nature of the ABCC through materials obtained in the United States and interviews with A-bomb survivors, family members, and other pertinent people.

Regret over unfulfilled research on residual radiation

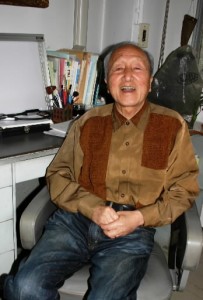

With a soft smile, Hideya Tamagaki, 84, a physician and a resident of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, took out a stack of A-4 size paper. “At this point in my life, I’ve developed a desire to make a record of my work when I was in my prime,” he said.

Back then, Dr. Tamagaki worked for the ABCC. Starting in 1949, and for the next 16 years, he served as a doctor in the heredity and clinical divisions. It was a time when the ABCC faced strong opposition from A-bomb survivors.

Dr. Tamagaki said that his “only regret” was the ABCC’s unfulfilled research into the effects of residual radiation from the bomb.

During the early 1950s, Dr. Tamagaki and his colleagues conducted a survey on 42 suspected cases involving the effects of residual radiation among those who entered an area close to the hypocenter shortly after the blast or took part in rescue operations. The actions of these survivors were plotted on a map, and they underwent medical examinations and blood tests. Some clearly seemed to have acute symptoms of radiation poisoning, such as vomiting, hair loss, and bleeding gums. A report on their health was then compiled.

However, the research was discontinued after this “preliminary survey” was carried out. Scientists at the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission had expressed opposition with the reasoning that infectious diseases, such as dysentery and typhoid fever, can cause similar symptoms. For U.S. science at the time, considering residual radiation as the cause was unthinkable.

Dr. Tamagaki countered by saying, “It’s unlikely that those who entered Hiroshima and took part in relief efforts suffered from poor nutrition or infectious diseases. I still believe the possibility that the health of these people was impaired by residual radiation should not be ruled out.”

Dr. Tamagaki lost family members in the atomic bombing. His home was located about 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. At the time, he was in Tsuruoka, Yamagata Prefecture, in northern Japan, where his medical school had moved to evacuate from Hiroshima prior to the A-bomb attack. There, he heard about the city’s annihilation by a new type of bomb. Unnerved, he returned to Hiroshima three weeks after the bombing. His mother was dead, and his sister was close to death after being exposed to the blast a short distance away. His father, who ran his own clinic near their home, suffered broken bones after being buried beneath a collapsed building. He was also experiencing acute symptoms of radiation sickness, but persisted in providing medical care to the survivors.

After Dr. Tamagaki began working at the ABCC, he sometimes faced hostility from survivors. When he tried to persuade survivors to pursue medical care, some vented their grievances about the atomic bombing his way. When he took blood samples, they complained bitterly. “I understood how they felt, so I couldn’t argue with them when they yelled at me,” he said.

For this reason, he repeatedly told younger colleagues, “The survivors are not hospital patients. Never forget that we’re asking for their cooperation.” Dr. Tamagaki objects to the idea that the ABCC was a research institute which provided no medical treatment. “We had 12 beds in three rooms and treated survivors for leukemia, pneumonia, gout, and other ailments,” he said.

“It’s only natural, I think, that the survivors attribute their diseases to the atomic bombing,” said Dr. Tamagaki. But he added that a doctor’s intuition is one thing and the results of a study based on data is another. Because the study on the effects of residual radiation was not completed, there were not enough samples to draw a conclusion.

In the prime of his working life, he was torn between Japan and the United States in his role as a scientist.

(Originally published on June 6, 2007)