Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 4 [3]

Jun. 21, 2016

In a nuclear superpower: Research of health risks near nuclear power plants

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Compared to the effects on human health of a massive amount of radiation released instantaneously by an atomic bomb, it is very difficult to determine how long-term, gradual exposure to small levels of radiation affects human health. Likewise, compared to nuclear experiments and nuclear weapons development facilities, it is much harder to ascertain the health risks of radiation exposure in the vicinity of nuclear power plants, operated in line with various standards and regulations. In the United States, a nuclear superpower, a planned research project on the health of people living near the nation’s nuclear power plants was canceled last summer. Among those concerned, some wish to pursue this scientific research while others view the effort with less enthusiasm.

Suspicions and anxiety smolder

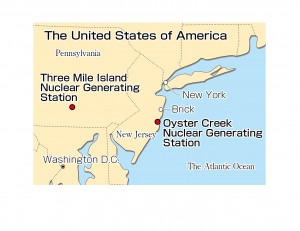

Nice homes and lush greenery line the waterfront of Brick, New Jersey. Brick is located little more than an hour’s drive south of New York City and its many high-rise buildings clustered together. Brick is known as a comfortable place to live. Janet Tauro, 56, says with a smile that some people move to Brick after they retire. However, she now worries about the nuclear power plant, the same one in Fukushima, that is located not far from her home.

The power plant in question is the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, which stands along the river about 30 kilometers south of her residence. It began operating in 1969 and is the oldest running nuclear power plant in the United States.

Ms. Tauro, an activist with a local environmental group, has called for the power station to be decommissioned, arguing that radioactive tritium, which was emitted from the power plant and leaked into an underground water source, has impacted the lives of local residents. In October 2012, the east coast was hit by a powerful hurricane, and because there was the possibility of flooding at the nuclear plant, a state of emergency was declared. Ms. Tauro recalled the earthquake and tsunami that struck the eastern part of Japan in 2011 and inundated the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, run by the Tokyo Electric Power Company, and the subsequent loss of power that led to that catastrophe.

The operator of the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station has previously announced that it will end operations at the plant by 2019, which is 10 years earlier than the original decision on its closure. This revised plan came to pass after the state authority demanded that the operator install cooling towers to prevent the release of heated waste water from polluting the environment. Coupled with sluggish oil prices, the operator decided to forgo any further investments in the aging nuclear power plant.

Ms. Tauro, however, contends that this won’t mean the end of the existence of the nuclear power plant. Furthermore, she says that the decommissioning work will also bring new risks and that all residents will have to be on alert.

In this regard, there is another concern. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), which is responsible for the safety regulations at nuclear power facilities, announced last summer that it will end the study being pursued on cancer risks involving the people living near nuclear power plants.

The National Academy of Science (NAS), to which the NRC committed a preliminary investigation, examined the feasibility of the risk study, the study methods to be adopted, and the scope of subjects, and submitted their first report in 2012. Based on the comparisons made regarding the nuclear power plant’s service period, the size of the local community, and data on various kinds of radioactive materials released into the environment, the NAS selected seven power plants including the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, and listed such options as an epidemiology study of the people living within a 50-kilometer radius of the power plants as a preliminary study. In 2014, the NAS submitted its report on the first half of the preliminary study.

The NRC explained that if it were to follow the NAS’s recommendation, the preliminary study alone would cost 8 million dollars (about 832 million yen) and the full-fledged study would take 15 years. As a result, the NRC changed its policy and decided to closely observe the investigations and research efforts carried out by other research institutes.

In late April, some members of the local environmental group met at Ms. Tauro’s house to discuss the matter. Local residents say that there are numerous cases of childhood cancers and miscarriages in the vicinity of the nuclear power plant. Given that the preliminary study may be able to clarify the residents’ concerns regarding the risks to their health, Ms. Tauro said angrily that 8 million dollars is not a high price to pay. However, Paula Gotsch, 80, added that she believes “No health risks” is already the foregone conclusion of the preliminary study and that she would not be surprised if the nuclear power industry applied pressure to have the study discontinued.

Residents showing interest in the issue hold mixed feelings: The study could be a precious opportunity to determine the health effects of exposure to low-dose radiation; the study was canceled in an attempt to hide the truth. Nevertheless, the residents have the same desire: They want to obtain reliable data gathered from a neutral perspective.

Researchers have mixed feelings

There are some things that cannot be ascertained by conducting studies of adult men. These include the health risks for fetuses and the connection to the development of childhood leukemia. Research should be carried out to clarify such issues.

Cindy Forker, 47, stressed the points mentioned above at a symposium held by the “Beyond Nuclear,” an anti-nuclear group in Washington D.C., in early May to mark the fifth anniversary of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. She made these remarks in the wake of the announcement by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) that the cancer risk study in the vicinity of American nuclear power plants would be brought to a halt due to the scale of the costs and the length of time required.

Timothy Mousseau, a professor at the University of South Carolina who was invited to the symposium, was involved in the preparation of a 2012 report as an expert committee member of the National Academy of Science (NAS) commissioned by the NRC. In an interview at a later date, he said that he had no idea if another reason actually exists for terminating the study. At the same time, he also mentioned the difficulty of continuing the study when it is not known whether the monetary investment could in fact lead to achieving a substantive result. There is even a possibility that the study would fail to confirm any ill effects on health even if such effects are present.

One factor in these difficulties is the “quality” of the data obtained. When studying the amount of radioactive materials released into the environment, it is not only the average amount emitted that must be determined but also the higher and lower values of this amount. Professor Mousseau argues that it is also necessary to observe the actual effects on human health at the time of an instantaneous spike in the amount released. Under current circumstances, however, collecting such data is not easy.

It is not easy to collect good quality data with regard to health, either. Mr. Mousseau points out that, unlike Japan’s universal healthcare system where all medical examination data is recorded and any history of the incidence of cancer is precisely identified, there are many cases where the cause of death does not help identify the disease suffered by the deceased. This means that although a patient may have suffered from cancer, a different disease is recorded as the cause of death.

Still, Mr. Mousseau believes that the cancer risk study should be continued, and he laments that the study was terminated. The study would be of significance, he said, even if the results it produced were only presented to the local residents who worry about the risks to their health. For that purpose, Mr. Mousseau feels that the budget is not extravagant. He feels that the study is not being pursued because the nuclear power industry does not want to dig up compelling information that may suggest there are effects on human health. But he maintains that it would be better, for both the residents and the industry itself, to first obtain these results from the study in order to deepen their knowledge about the risks involved.

Allison Macfarlane, who chaired the NRC from July 2012 to the end of 2014, asserts that, during her term, there was no opposition to the policy to proceed with the plan. But, she says, Congress applies constant pressure on the NRC to reduce its budget.

The priority placed on policy and costs; the intent of Congress and industry; and the sentiments of local residents: These are all intricately intertwined with scientific pursuit.

Different conclusions on Three Mile Island accident

It is not only the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant that is behind the concerns over the release of radioactive materials from these facilities into the environment. The memory of the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in March 1979 also haunts the present.

When that accident occurred, the No. 2 reactor had just begun operating in the suburbs of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, located in the northeastern part of the United States. A combination of operating errors and malfunctions caused the reactor to lose its cooling function, which led to a core meltdown. The accident at Three Mile Island was one of the world’s worst nuclear accidents, after the accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima.

However, the amount of nuclear materials released into the environment was not as large because the nuclear fuel was confined to the containment vessel. Also, it has been reported that because local residents were fortunately evacuated from the area, their radiation exposure was no more than 1 mSv. The results of a survey of residents published by the state authority in 1981 showed that there was no increase in child mortality rates within a radius of 10 miles (18 kilometers) of the power plant.

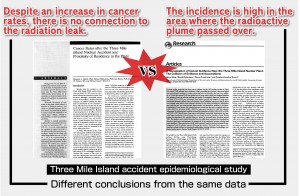

A series of epidemiological studies conducted by experts, however, have reached a conflicting conclusion.

A research team from Columbia University analyzed the medical records of the residents both 10 years before and after the nuclear accident. Although there was an increase in the number of cancer cases after the nuclear accident, the team concluded that there was no relationship between the radiation release and cancer risks and suggested that this increase was probably due to the stress they feel or the greater frequency of their health checkups.

Residents who were dissatisfied with this result asked a team from the University of North Carolina to carry out another study using the same data. This team at the university then concluded that there was a high incidence of leukemia and lung cancer in an area where the radioactive plumes were believed to have passed over in the wake of the accident. In addition, based on the residents’ testimony concerning the conditions in the immediate aftermath of the accident, the team pointed out that the dose of radiation exposure was much higher than what was stated by the power company and the government.

In epidemiological studies, outcomes are dependent on the aspects of data on which the researchers focus and on the calculation model used. This is particularly true when the number of subjects in a study is limited or when the difference in the findings is small.

In studies carried out on Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bomb survivors, it is said that light will be shed on some issues by persisting in these studies until the time all the survivors have passed away. In the case of the residents living near the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant, where the radiation exposure is much lower than in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, studying the effects on the health of residents is significantly more difficult than these efforts involving the A-bomb survivors.

(Originally published on June 21, 2016)

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Compared to the effects on human health of a massive amount of radiation released instantaneously by an atomic bomb, it is very difficult to determine how long-term, gradual exposure to small levels of radiation affects human health. Likewise, compared to nuclear experiments and nuclear weapons development facilities, it is much harder to ascertain the health risks of radiation exposure in the vicinity of nuclear power plants, operated in line with various standards and regulations. In the United States, a nuclear superpower, a planned research project on the health of people living near the nation’s nuclear power plants was canceled last summer. Among those concerned, some wish to pursue this scientific research while others view the effort with less enthusiasm.

Suspicions and anxiety smolder

Nice homes and lush greenery line the waterfront of Brick, New Jersey. Brick is located little more than an hour’s drive south of New York City and its many high-rise buildings clustered together. Brick is known as a comfortable place to live. Janet Tauro, 56, says with a smile that some people move to Brick after they retire. However, she now worries about the nuclear power plant, the same one in Fukushima, that is located not far from her home.

The power plant in question is the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, which stands along the river about 30 kilometers south of her residence. It began operating in 1969 and is the oldest running nuclear power plant in the United States.

Ms. Tauro, an activist with a local environmental group, has called for the power station to be decommissioned, arguing that radioactive tritium, which was emitted from the power plant and leaked into an underground water source, has impacted the lives of local residents. In October 2012, the east coast was hit by a powerful hurricane, and because there was the possibility of flooding at the nuclear plant, a state of emergency was declared. Ms. Tauro recalled the earthquake and tsunami that struck the eastern part of Japan in 2011 and inundated the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, run by the Tokyo Electric Power Company, and the subsequent loss of power that led to that catastrophe.

The operator of the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station has previously announced that it will end operations at the plant by 2019, which is 10 years earlier than the original decision on its closure. This revised plan came to pass after the state authority demanded that the operator install cooling towers to prevent the release of heated waste water from polluting the environment. Coupled with sluggish oil prices, the operator decided to forgo any further investments in the aging nuclear power plant.

Ms. Tauro, however, contends that this won’t mean the end of the existence of the nuclear power plant. Furthermore, she says that the decommissioning work will also bring new risks and that all residents will have to be on alert.

In this regard, there is another concern. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), which is responsible for the safety regulations at nuclear power facilities, announced last summer that it will end the study being pursued on cancer risks involving the people living near nuclear power plants.

The National Academy of Science (NAS), to which the NRC committed a preliminary investigation, examined the feasibility of the risk study, the study methods to be adopted, and the scope of subjects, and submitted their first report in 2012. Based on the comparisons made regarding the nuclear power plant’s service period, the size of the local community, and data on various kinds of radioactive materials released into the environment, the NAS selected seven power plants including the Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, and listed such options as an epidemiology study of the people living within a 50-kilometer radius of the power plants as a preliminary study. In 2014, the NAS submitted its report on the first half of the preliminary study.

The NRC explained that if it were to follow the NAS’s recommendation, the preliminary study alone would cost 8 million dollars (about 832 million yen) and the full-fledged study would take 15 years. As a result, the NRC changed its policy and decided to closely observe the investigations and research efforts carried out by other research institutes.

In late April, some members of the local environmental group met at Ms. Tauro’s house to discuss the matter. Local residents say that there are numerous cases of childhood cancers and miscarriages in the vicinity of the nuclear power plant. Given that the preliminary study may be able to clarify the residents’ concerns regarding the risks to their health, Ms. Tauro said angrily that 8 million dollars is not a high price to pay. However, Paula Gotsch, 80, added that she believes “No health risks” is already the foregone conclusion of the preliminary study and that she would not be surprised if the nuclear power industry applied pressure to have the study discontinued.

Residents showing interest in the issue hold mixed feelings: The study could be a precious opportunity to determine the health effects of exposure to low-dose radiation; the study was canceled in an attempt to hide the truth. Nevertheless, the residents have the same desire: They want to obtain reliable data gathered from a neutral perspective.

Researchers have mixed feelings

There are some things that cannot be ascertained by conducting studies of adult men. These include the health risks for fetuses and the connection to the development of childhood leukemia. Research should be carried out to clarify such issues.

Cindy Forker, 47, stressed the points mentioned above at a symposium held by the “Beyond Nuclear,” an anti-nuclear group in Washington D.C., in early May to mark the fifth anniversary of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. She made these remarks in the wake of the announcement by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) that the cancer risk study in the vicinity of American nuclear power plants would be brought to a halt due to the scale of the costs and the length of time required.

Timothy Mousseau, a professor at the University of South Carolina who was invited to the symposium, was involved in the preparation of a 2012 report as an expert committee member of the National Academy of Science (NAS) commissioned by the NRC. In an interview at a later date, he said that he had no idea if another reason actually exists for terminating the study. At the same time, he also mentioned the difficulty of continuing the study when it is not known whether the monetary investment could in fact lead to achieving a substantive result. There is even a possibility that the study would fail to confirm any ill effects on health even if such effects are present.

One factor in these difficulties is the “quality” of the data obtained. When studying the amount of radioactive materials released into the environment, it is not only the average amount emitted that must be determined but also the higher and lower values of this amount. Professor Mousseau argues that it is also necessary to observe the actual effects on human health at the time of an instantaneous spike in the amount released. Under current circumstances, however, collecting such data is not easy.

It is not easy to collect good quality data with regard to health, either. Mr. Mousseau points out that, unlike Japan’s universal healthcare system where all medical examination data is recorded and any history of the incidence of cancer is precisely identified, there are many cases where the cause of death does not help identify the disease suffered by the deceased. This means that although a patient may have suffered from cancer, a different disease is recorded as the cause of death.

Still, Mr. Mousseau believes that the cancer risk study should be continued, and he laments that the study was terminated. The study would be of significance, he said, even if the results it produced were only presented to the local residents who worry about the risks to their health. For that purpose, Mr. Mousseau feels that the budget is not extravagant. He feels that the study is not being pursued because the nuclear power industry does not want to dig up compelling information that may suggest there are effects on human health. But he maintains that it would be better, for both the residents and the industry itself, to first obtain these results from the study in order to deepen their knowledge about the risks involved.

Allison Macfarlane, who chaired the NRC from July 2012 to the end of 2014, asserts that, during her term, there was no opposition to the policy to proceed with the plan. But, she says, Congress applies constant pressure on the NRC to reduce its budget.

The priority placed on policy and costs; the intent of Congress and industry; and the sentiments of local residents: These are all intricately intertwined with scientific pursuit.

Different conclusions on Three Mile Island accident

It is not only the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant that is behind the concerns over the release of radioactive materials from these facilities into the environment. The memory of the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in March 1979 also haunts the present.

When that accident occurred, the No. 2 reactor had just begun operating in the suburbs of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, located in the northeastern part of the United States. A combination of operating errors and malfunctions caused the reactor to lose its cooling function, which led to a core meltdown. The accident at Three Mile Island was one of the world’s worst nuclear accidents, after the accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima.

However, the amount of nuclear materials released into the environment was not as large because the nuclear fuel was confined to the containment vessel. Also, it has been reported that because local residents were fortunately evacuated from the area, their radiation exposure was no more than 1 mSv. The results of a survey of residents published by the state authority in 1981 showed that there was no increase in child mortality rates within a radius of 10 miles (18 kilometers) of the power plant.

A series of epidemiological studies conducted by experts, however, have reached a conflicting conclusion.

A research team from Columbia University analyzed the medical records of the residents both 10 years before and after the nuclear accident. Although there was an increase in the number of cancer cases after the nuclear accident, the team concluded that there was no relationship between the radiation release and cancer risks and suggested that this increase was probably due to the stress they feel or the greater frequency of their health checkups.

Residents who were dissatisfied with this result asked a team from the University of North Carolina to carry out another study using the same data. This team at the university then concluded that there was a high incidence of leukemia and lung cancer in an area where the radioactive plumes were believed to have passed over in the wake of the accident. In addition, based on the residents’ testimony concerning the conditions in the immediate aftermath of the accident, the team pointed out that the dose of radiation exposure was much higher than what was stated by the power company and the government.

In epidemiological studies, outcomes are dependent on the aspects of data on which the researchers focus and on the calculation model used. This is particularly true when the number of subjects in a study is limited or when the difference in the findings is small.

In studies carried out on Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bomb survivors, it is said that light will be shed on some issues by persisting in these studies until the time all the survivors have passed away. In the case of the residents living near the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant, where the radiation exposure is much lower than in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, studying the effects on the health of residents is significantly more difficult than these efforts involving the A-bomb survivors.

(Originally published on June 21, 2016)