Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Recreating cityscapes: Hatchobori was busy area since before war

Feb. 17, 2020

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

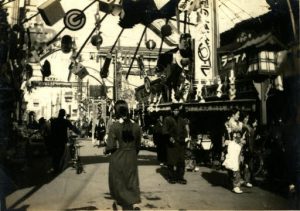

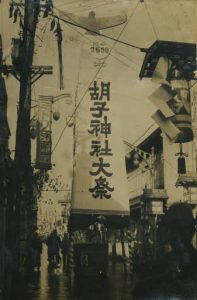

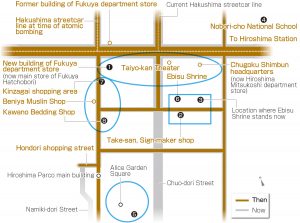

Even before the atomic bombing, Hatchobori, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, was a bustling shopping district that served as a city landmark. After a streetcar began to operate between Hiroshima station and Hiroshima’s downtown in 1912, financial and recreational establishments were concentrated in Hatchobori along the streetcar tracks. The district was in those days packed with shoppers. Located roughly one kilometer from the hypocenter, Hatchobori was destroyed 75 years ago, on August 6. After the end of World War II, reconstruction of department stores and shopping streets in the area symbolized Hiroshima’s recovery. Based on valuable photographs that escaped the fires and comments from people who had resided in the area, the Chugoku Shimbun herein takes a look at the old downtown district that was lost in the atomic bombing.

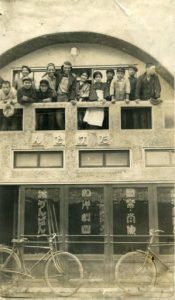

In one photo, a man wearing a hat and bow-tie smiles widely while standing on a balcony surrounded by apprentices. On the wall and glass doors at the store entrance, decorative writing is visible: “Take-san,” the shop’s name, “Design and Portraits,” “Japanese and Western Comics,” and “Signs.”

Kiyoko Takenaga, 89, has carefully held onto the photo. Ms. Takenaga was born and raised in Ebisu-cho (now Horikawa-cho in Naka Ward, Hiroshima). “This man is my father. I believe the photo was taken around 1930, the year I was born. This is the only photo showing the appearance of my house,” said Ms. Takenaga.

Her father, Santaro, opened a sign maker’s shop at his home, which stood in front of Ebisu Shrine, during the Taisho period, when he was in his twenties. Around that time, numerous movie theaters and stage theaters including Taiyo-kan, Toyo-za, and Kabuki-za were built in Hatchobori. Take-san, her father’s shop, was an eye-catching establishment with big signboards displayed in front.

Ms. Takenaga explained, “The Amako Soy Sauce store was located in front of my house. I played hide-and-seek with my friends in its warehouse in which many large wooden barrels for making soy sauce were stored. I frequently lost my way because it was dark inside.” She added, “Behind the soy sauce shop was the Taiyo-kan movie theater. One time, when my father’s apprentices took a signboard to the theater on a two-wheeled handcart, I tagged along, quietly snuck in, and got to watch a movie.”

About 80 shops were lined up in the Hatchobori district, including the Kinzagai shopping area, located right next to Ebisu-machi. In 1929, Fukuya opened in Hatchobori as the first department store in Hiroshima. Hatchobori was said to be gorgeous.

However, orders for signs decreased in number with the deteriorating state of the war, as the business was linked with public entertainment. With that, Santaro changed his business to that of an antique art dealer. In his neighborhood, many families were forced to leave their houses because of the efforts to create fire lanes by dismantling houses and buildings to prevent the spread of fire in the case of air raids.

On August 6, 1945, the entire Hatchobori area was directly hit by the A-bomb blast and thermal rays, becoming a burnt wasteland with only the reinforced concrete buildings such as the Fukuya Department Store and banks remaining.

Ms. Takenaga’s mother Shin died at home in the bombing, and her elder sister Takako, who was then 16, passed away at Sen-tei (now Shukkeien Garden), near her home. Their remains have yet to be found. Her 12-year-old sister Teruko was severely burned in the atomic bombing when she was mobilized to engage in the dismantling of buildings in the central area in the city. Infested with maggots, she died eight days after the end of the war. Ms. Takenaga said, “Teruko was an innocent, but she died such a horrible death. Poor girl...”

Ms. Takenaga was then a third-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior & Senior High School) and was working as a mobilized student at the Hiroshima Finance Bureau. The office was about 800 meters from the hypocenter. Though she was trapped under rubble, she somehow managed to escape. Along with other family members who survived, she fled to Obayashi (now part of Asakita Ward), her father’s birthplace. Both she and her father suffered from acute symptoms caused by exposure to radiation such as loss of hair and vomiting of blood.

Still, saying “I will definitely return to Ebisu-cho,” Santaro traveled about 20 kilometers there every day on his bicycle, starting about six months after the bombing, and built a barracks in which to live on the ruined site. He contributed to reconstruction of the area with other residents who had survived the atomic bombing. Ms. Takenaga still lives in the place left by her father.

Miyako Makino, 85, is Ms. Takenaga’s childhood friend who now lives in Hatsukaichi. Ms. Makino’s parental home was the kimono fabrics shop Beniya Muslin, located in the Kinzagai shopping area. Her parents were killed in the atomic bombing. Afterward, she was raised by her grandmother and changed elementary schools frequently. Now, almost every week, she visits the area where she grew up.

Ms. Takenaga and Ms. Makino walked together from the Kinzagai shopping area, where Ms. Makino’s home once stood, to the Ebisu Shrine, where they once played together. They talked for a long time about their childhood memories, asking if the other remembered playing with friends on the grounds of the shrine, for example. They also recalled, however, how their homes, families, and neighborhoods were lost in an instant.

Hatchobori is still busy with many shoppers today. Traces of the atomic bombing in the vicinity are difficult to discern now, but both women have kept alive the memories they had of Hatchobori prior to that day, August 6.

(Originally published on February 17, 2020)

Even before the atomic bombing, Hatchobori, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward, was a bustling shopping district that served as a city landmark. After a streetcar began to operate between Hiroshima station and Hiroshima’s downtown in 1912, financial and recreational establishments were concentrated in Hatchobori along the streetcar tracks. The district was in those days packed with shoppers. Located roughly one kilometer from the hypocenter, Hatchobori was destroyed 75 years ago, on August 6. After the end of World War II, reconstruction of department stores and shopping streets in the area symbolized Hiroshima’s recovery. Based on valuable photographs that escaped the fires and comments from people who had resided in the area, the Chugoku Shimbun herein takes a look at the old downtown district that was lost in the atomic bombing.

Theaters, shops, and shrine used as playground were all lost in bombing

In one photo, a man wearing a hat and bow-tie smiles widely while standing on a balcony surrounded by apprentices. On the wall and glass doors at the store entrance, decorative writing is visible: “Take-san,” the shop’s name, “Design and Portraits,” “Japanese and Western Comics,” and “Signs.”

Kiyoko Takenaga, 89, has carefully held onto the photo. Ms. Takenaga was born and raised in Ebisu-cho (now Horikawa-cho in Naka Ward, Hiroshima). “This man is my father. I believe the photo was taken around 1930, the year I was born. This is the only photo showing the appearance of my house,” said Ms. Takenaga.

Her father, Santaro, opened a sign maker’s shop at his home, which stood in front of Ebisu Shrine, during the Taisho period, when he was in his twenties. Around that time, numerous movie theaters and stage theaters including Taiyo-kan, Toyo-za, and Kabuki-za were built in Hatchobori. Take-san, her father’s shop, was an eye-catching establishment with big signboards displayed in front.

Ms. Takenaga explained, “The Amako Soy Sauce store was located in front of my house. I played hide-and-seek with my friends in its warehouse in which many large wooden barrels for making soy sauce were stored. I frequently lost my way because it was dark inside.” She added, “Behind the soy sauce shop was the Taiyo-kan movie theater. One time, when my father’s apprentices took a signboard to the theater on a two-wheeled handcart, I tagged along, quietly snuck in, and got to watch a movie.”

About 80 shops were lined up in the Hatchobori district, including the Kinzagai shopping area, located right next to Ebisu-machi. In 1929, Fukuya opened in Hatchobori as the first department store in Hiroshima. Hatchobori was said to be gorgeous.

However, orders for signs decreased in number with the deteriorating state of the war, as the business was linked with public entertainment. With that, Santaro changed his business to that of an antique art dealer. In his neighborhood, many families were forced to leave their houses because of the efforts to create fire lanes by dismantling houses and buildings to prevent the spread of fire in the case of air raids.

On August 6, 1945, the entire Hatchobori area was directly hit by the A-bomb blast and thermal rays, becoming a burnt wasteland with only the reinforced concrete buildings such as the Fukuya Department Store and banks remaining.

Ms. Takenaga’s mother Shin died at home in the bombing, and her elder sister Takako, who was then 16, passed away at Sen-tei (now Shukkeien Garden), near her home. Their remains have yet to be found. Her 12-year-old sister Teruko was severely burned in the atomic bombing when she was mobilized to engage in the dismantling of buildings in the central area in the city. Infested with maggots, she died eight days after the end of the war. Ms. Takenaga said, “Teruko was an innocent, but she died such a horrible death. Poor girl...”

Ms. Takenaga was then a third-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior & Senior High School) and was working as a mobilized student at the Hiroshima Finance Bureau. The office was about 800 meters from the hypocenter. Though she was trapped under rubble, she somehow managed to escape. Along with other family members who survived, she fled to Obayashi (now part of Asakita Ward), her father’s birthplace. Both she and her father suffered from acute symptoms caused by exposure to radiation such as loss of hair and vomiting of blood.

Still, saying “I will definitely return to Ebisu-cho,” Santaro traveled about 20 kilometers there every day on his bicycle, starting about six months after the bombing, and built a barracks in which to live on the ruined site. He contributed to reconstruction of the area with other residents who had survived the atomic bombing. Ms. Takenaga still lives in the place left by her father.

Miyako Makino, 85, is Ms. Takenaga’s childhood friend who now lives in Hatsukaichi. Ms. Makino’s parental home was the kimono fabrics shop Beniya Muslin, located in the Kinzagai shopping area. Her parents were killed in the atomic bombing. Afterward, she was raised by her grandmother and changed elementary schools frequently. Now, almost every week, she visits the area where she grew up.

Ms. Takenaga and Ms. Makino walked together from the Kinzagai shopping area, where Ms. Makino’s home once stood, to the Ebisu Shrine, where they once played together. They talked for a long time about their childhood memories, asking if the other remembered playing with friends on the grounds of the shrine, for example. They also recalled, however, how their homes, families, and neighborhoods were lost in an instant.

Hatchobori is still busy with many shoppers today. Traces of the atomic bombing in the vicinity are difficult to discern now, but both women have kept alive the memories they had of Hatchobori prior to that day, August 6.

(Originally published on February 17, 2020)