Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Unclaimed A-bomb victims’ remains, Part 9: Stance of the Japanese government

Feb. 14, 2020

by Yo Kono and Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writers

“Never will we forget the large number of war dead whose remains have still not been recovered. We will take it as our mission to spare no effort to enable their remains to return to their hometowns at the earliest possible time.” Those words were spoken by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the National Memorial Ceremony for the War Dead on August 15, 2019, the 74th commemoration of World War II’s conclusion.

The ceremony was held by Japan’s national government at the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo. Prime Minister Abe delivered his address in front of a memorial pillar labeled “Souls of the Nation’s War Dead.” Also participating in the ceremony were representatives of bereaved family members from each prefecture, the Japanese Emperor and Empress, National Diet members, and representatives of A-bomb victims’ families. The audience of about 5,000 listened in silence to Mr. Abe’s declaration.

His words about the collection of remains are backed by a law enacted in April 2016 designed to facilitate recovery of war-dead remains. Tokyo has collected war-dead remains on the Pacific Islands, which experienced fierce battles during the war, at Siberian labor camp sites in the former Soviet Union, where Japanese soldiers were held after the war, and other sites. The law stipulates that the recovery of such remains is the Japanese government’s responsibility. DNA analysis of remains is now used to confirm identify. When remains cannot be returned to surviving family, they are stored at the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery in Tokyo.

In Hiroshima, the city government of Hiroshima and private individuals have unearthed remains of A-bomb victims. Is there no way to gain the national government’s support and involvement in this work?

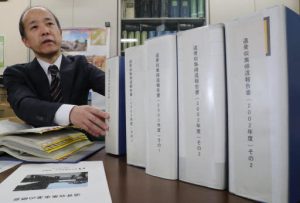

“Such efforts do not fall within the scope of assistance from the government,” said Yukio Tanabe, Deputy Director of the Office for the Recovery and Repatriation of the Remains of War Dead and Memorial Services for War Dead, Social Welfare and War Victims’ Relief Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, located in Kasumigaseki, Tokyo. Office for the Recovery and Repatriation of the Remains of War Dead and memorial services for war dead.

“War-dead” designation limited to certain victims

The Japanese government fundamentally defines “war dead” as military personnel or civilians employed by the Japanese military who died in battle. Among such war dead, the law for recovery of war-dead remains applies specifically to military personnel or civilians employed by the military who died during land battles in the final stages of Japan’s involvement in World War II. Collection of remains is, in principle, conducted overseas, with such work in Japan limited to Okinawa and the island of Iwo Jima.

“Damage by the atomic bombing is defined as general war damage. If A-bomb victims’ remains need to be recovered, I believe it’s something local governments should do,” said Mr. Tanabe. When asked about the rationale for his assumption, he provided an unexpected answer: the law stipulates specifically how to deal with unidentified ill or unidentified deceased.

Unidentified deceased can point to someone who falls on the street and dies. Concerning unidentified corpses, the law stipulates that local municipalities are responsible for informing the bereaved family. “Though the law doesn’t include statements about general-war damage specifically, I assume it would also apply to the remains of unidentified A-bomb victims,” said Mr. Tanabe.

In fact, because Hiroshima was a military city, many soldiers died in the atomic bombing. The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the city’s Naka Ward, has in storage large numbers of remains, some of which are contained in boxes with the label “Soldier who died during the war with name unidentified,” and a small quantity of remains with names identified. Hiroshima City sends posters listing the names of 814 unclaimed A-bomb victims, including both civilians and soldiers, to local municipalities throughout Japan to seek further information about those listed.

Japanese government not actively involved

A Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare official said it responds to requests for identify confirmation of remains of soldiers who died in the atomic bombing, when an inquiry is made by bereaved family or prefectural governments. Nevertheless, Tokyo is not proactively involved in the collection and return of remains.

We also asked an official at the ministry’s A-bomb Survivors Support Office regarding why the Japanese government does not recover the remains of A-bomb survivors. In addition to development of measures related to issuance of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and granting of health care benefits, the office is in charge of providing subsidies to projects aimed at preservation of A-bombed buildings and trees. Collection of A-bomb victims’ remains may not be part of its duties, but the office should be able to at least take action to encourage that the list of 814 unclaimed A-bomb victims’ names is known more broadly throughout Japan.

Takehiro Ono, director of the office, however, admitted he did not know Hiroshima City was searching for bereaved family of unclaimed victims. “This office is responsible for providing support and relief to the A-bomb survivors who are alive,” Mr. Ono said. “I’m not sure if the return of A-bomb victims’ remains is something the national government should assist.

For almost 75 years, Tokyo has consistently avoided implementation of a survey and other efforts to discover accurate numbers of A-bomb victims. In other words, the government’s stance is equivalent to pushing Hiroshima City and Prefecture to account for the actual damage wrought by the atomic bombing. A barrier seems to exist in what is a doctrine of perseverance, which posits that all citizens in the nation should accept and endure damage that the public suffers as a result of war begun by the government, rather than the government taking responsibility for the war and compensating citizens for such damage.

Remains of A-bomb victims are still buried underground on the islands of Ninoshima and Kanawa (both now part of Minami Ward) off the coast of the city of Hiroshima. Yuji Egusa, 92, is a resident of Fuchu-cho and the head of the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association. “It’s necessary to collect the victims’ remains and examine them thoroughly.” Mr. Egusa was on the island of Kanawa as a mobilized student when he experienced the atomic bombing. Conducting such an investigation also means conveying to others the stories of the lives of countless numbers of people who were tragically killed.

Keywords

General war victims

This definition of victims comprises those who suffered from the air raids and other attacks on big cities. As for A-bomb survivors, the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law stipulates that the national government should provide relief measures, considering that the survivors’ health effects caused by A-bomb radiation is unique and different from other damage caused by war. However, the law does not include any clear indication about national compensation.

(Originally published on February 14, 2020)

National government claims collection of remains up to local governments

Law designed to facilitate recovery of war-dead remains not applied to “General war damage”

“Never will we forget the large number of war dead whose remains have still not been recovered. We will take it as our mission to spare no effort to enable their remains to return to their hometowns at the earliest possible time.” Those words were spoken by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the National Memorial Ceremony for the War Dead on August 15, 2019, the 74th commemoration of World War II’s conclusion.

The ceremony was held by Japan’s national government at the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo. Prime Minister Abe delivered his address in front of a memorial pillar labeled “Souls of the Nation’s War Dead.” Also participating in the ceremony were representatives of bereaved family members from each prefecture, the Japanese Emperor and Empress, National Diet members, and representatives of A-bomb victims’ families. The audience of about 5,000 listened in silence to Mr. Abe’s declaration.

His words about the collection of remains are backed by a law enacted in April 2016 designed to facilitate recovery of war-dead remains. Tokyo has collected war-dead remains on the Pacific Islands, which experienced fierce battles during the war, at Siberian labor camp sites in the former Soviet Union, where Japanese soldiers were held after the war, and other sites. The law stipulates that the recovery of such remains is the Japanese government’s responsibility. DNA analysis of remains is now used to confirm identify. When remains cannot be returned to surviving family, they are stored at the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery in Tokyo.

In Hiroshima, the city government of Hiroshima and private individuals have unearthed remains of A-bomb victims. Is there no way to gain the national government’s support and involvement in this work?

“Such efforts do not fall within the scope of assistance from the government,” said Yukio Tanabe, Deputy Director of the Office for the Recovery and Repatriation of the Remains of War Dead and Memorial Services for War Dead, Social Welfare and War Victims’ Relief Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, located in Kasumigaseki, Tokyo. Office for the Recovery and Repatriation of the Remains of War Dead and memorial services for war dead.

“War-dead” designation limited to certain victims

The Japanese government fundamentally defines “war dead” as military personnel or civilians employed by the Japanese military who died in battle. Among such war dead, the law for recovery of war-dead remains applies specifically to military personnel or civilians employed by the military who died during land battles in the final stages of Japan’s involvement in World War II. Collection of remains is, in principle, conducted overseas, with such work in Japan limited to Okinawa and the island of Iwo Jima.

“Damage by the atomic bombing is defined as general war damage. If A-bomb victims’ remains need to be recovered, I believe it’s something local governments should do,” said Mr. Tanabe. When asked about the rationale for his assumption, he provided an unexpected answer: the law stipulates specifically how to deal with unidentified ill or unidentified deceased.

Unidentified deceased can point to someone who falls on the street and dies. Concerning unidentified corpses, the law stipulates that local municipalities are responsible for informing the bereaved family. “Though the law doesn’t include statements about general-war damage specifically, I assume it would also apply to the remains of unidentified A-bomb victims,” said Mr. Tanabe.

In fact, because Hiroshima was a military city, many soldiers died in the atomic bombing. The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in the city’s Naka Ward, has in storage large numbers of remains, some of which are contained in boxes with the label “Soldier who died during the war with name unidentified,” and a small quantity of remains with names identified. Hiroshima City sends posters listing the names of 814 unclaimed A-bomb victims, including both civilians and soldiers, to local municipalities throughout Japan to seek further information about those listed.

Japanese government not actively involved

A Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare official said it responds to requests for identify confirmation of remains of soldiers who died in the atomic bombing, when an inquiry is made by bereaved family or prefectural governments. Nevertheless, Tokyo is not proactively involved in the collection and return of remains.

We also asked an official at the ministry’s A-bomb Survivors Support Office regarding why the Japanese government does not recover the remains of A-bomb survivors. In addition to development of measures related to issuance of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and granting of health care benefits, the office is in charge of providing subsidies to projects aimed at preservation of A-bombed buildings and trees. Collection of A-bomb victims’ remains may not be part of its duties, but the office should be able to at least take action to encourage that the list of 814 unclaimed A-bomb victims’ names is known more broadly throughout Japan.

Takehiro Ono, director of the office, however, admitted he did not know Hiroshima City was searching for bereaved family of unclaimed victims. “This office is responsible for providing support and relief to the A-bomb survivors who are alive,” Mr. Ono said. “I’m not sure if the return of A-bomb victims’ remains is something the national government should assist.

For almost 75 years, Tokyo has consistently avoided implementation of a survey and other efforts to discover accurate numbers of A-bomb victims. In other words, the government’s stance is equivalent to pushing Hiroshima City and Prefecture to account for the actual damage wrought by the atomic bombing. A barrier seems to exist in what is a doctrine of perseverance, which posits that all citizens in the nation should accept and endure damage that the public suffers as a result of war begun by the government, rather than the government taking responsibility for the war and compensating citizens for such damage.

Remains of A-bomb victims are still buried underground on the islands of Ninoshima and Kanawa (both now part of Minami Ward) off the coast of the city of Hiroshima. Yuji Egusa, 92, is a resident of Fuchu-cho and the head of the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association. “It’s necessary to collect the victims’ remains and examine them thoroughly.” Mr. Egusa was on the island of Kanawa as a mobilized student when he experienced the atomic bombing. Conducting such an investigation also means conveying to others the stories of the lives of countless numbers of people who were tragically killed.

Keywords

General war victims

This definition of victims comprises those who suffered from the air raids and other attacks on big cities. As for A-bomb survivors, the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law stipulates that the national government should provide relief measures, considering that the survivors’ health effects caused by A-bomb radiation is unique and different from other damage caused by war. However, the law does not include any clear indication about national compensation.

(Originally published on February 14, 2020)