Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 4)

Apr. 20, 2012

Reporters and photographers

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Camera pointed through tears

How did the reporters and photographers who lived through the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945 chronicle the devastation they saw in its aftermath? The offices of the Chugoku Shimbun burned down as a result of the A-bombing, and the company could not put out a paper. What sort of reporting did the reporters and photographers attempt to do under these circumstances? Who were the reporters of the “kudentai,” who raised their voices to tell of relief measures? What about the reports of the devastation of Hiroshima that was published with the end of the war? In this article the Chugoku Shimbun looks at the newspapermen who, despite experiencing the A-bombing, strove to cover the news.

Walking around conveying information verbally

Yoshito Matsushige, then 32, a photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun, was also a member of the news team of the Chugoku District Military Headquarters. On August 6 he greeted the dawn on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle.

Until his death at the age of 92, he spoke both in Japan and overseas about what he captured on film that day. He submitted some of his historic photographs along with an account of his experiences for publication in “The First Atomic Bomb Photographic Record of Hiroshima, Volume 1,” which was published by Asahi Publishing in 1952.

Mr. Matsushige had been on duty at the Chugoku District Military Headquarters because of air raid warnings that had been issued continuously since the night before. When he was relieved on the morning of August 6, he returned to his home in Midori-machi (now Nishi Midori-machi, Minami Ward). He ate breakfast and set out for work but returned home to use the toilet. Just then the atomic bomb was dropped. His home was 2.7 km southeast of the hypocenter.

“It was my fate to live. That’s why I was able to take those photos,” he once recalled in a conversation with this reporter. The windows were blown out of his home, where his wife and sister ran a barbershop. He found himself reaching for his waist, where his Mamiya 6 camera was ordinarily tied with a leather band, partly with thoughts of his occupation and partly because his camera was his most valuable possession.

Photographing devastation just after bombing

Mr. Matsushige crossed the Miyuki Bridge to the city’s downtown area and got as far as the vicinity of Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now the site of Hiroshima University’s Senda campus), but the intensity of the flames forced him to retreat.

Shortly after 11 a.m. he took a photo at the Miyuki Bridge, 2.2 km from the hypocenter, of a group of men and women, young and old, who had been exposed to thermal rays. “Although it’s the duty of a news photographer, when I came around to get close-ups of people’s faces, they looked so terrible…” Whenever he recounted his experiences of that day he cited the same reason for failing to take more photos: “The viewfinder was clouded by my tears.”

Shortly after 3 p.m. Mr. Matsushige arrived at Hatchobori, where the offices of the Chugoku Shimbun stood. There he saw dead bodies filling cisterns and the burned bodies of passengers on streetcars still hanging onto the straps. “Everywhere I went I pointed my camera at the scene and looked through it, but when I saw people groaning and begging for water and about to depart for the next world, I could not bring myself to press the shutter,” he said in an account published in 1952.

Nevertheless by shortly after 4 p.m. he had taken three shots on the west and east sides of the Miyuki Bridge and two more inside and outside his house, for a total of five pictures, capturing the misery of the people just after the atomic bombing.

The first picture taken from the ground just after the bomb exploded was shot by Seiso Yamada, 83, a resident of Fuchu-cho. At the time Mr. Yamada worked for the Chugoku Shimbun picking up manuscripts from news bureaus that had been delivered to train stations and post offices and bringing them to the paper’s downtown offices. In the evenings he attended classes at Hiroshima Municipal Third Junior High School. Mr. Yamada later wielded his pen as a sports reporter for the paper.

On August 6, he was invited to go on a picnic in nearby Mikumari Gorge by a childhood friend who had a day off from his job as a mobilized factory worker.

“At the start of the trail into the gorge I saw a B-29 and a parachute…” It was the blast measurement instrumentation that was dropped by parachute from one of the planes accompanying the Enola Gay.

Mr. Yamada saw a bright flash of light like that of a flashbulb going off. It was followed by a loud boom. He automatically hit the dirt.

“When I got up, I saw something like a red sun, and a cloud was billowing up beyond the pine forest. I wondered what it was.” He took a photograph with the Konica “Baby Pearl” camera he had brought with him.

Of the 25 photos of the mushroom cloud confirmed to have been taken from the ground, this was the first. It is believed to have been taken about 2 minutes after the blast. “Mr. Matsushige developed the film for me,” Mr. Yamada said.

But the historic photographs taken by Mr. Matsushige and Mr. Yamada were not published right away. The offices of the Chugoku Shimbun had been destroyed by fire, and the company could not publish its own paper. After the end of the war, citing the need to maintain confidentiality regarding the atomic bomb, the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ) imposed censorship effective September 19.

The photos taken by the two men were ultimately published on page 2 of the July 6, 1946 edition of “Evening Edition Hiroshima,” which was published by a company set up by the Chugoku Shimbun. Conscious of the censorship, the paper published the photographs along with an introductory article stating that they had been “introduced to the world by an American magazine.” Post-war coverage of the reality of the atomic bombing as well began under difficult conditions.

Governor’s announcement: “Believe in victory”

Let’s once again turn the clock back to August 6, 1945, and look into what the reporters and photographers were doing that day.

News reporter Ichiro Osako, then 32, had returned home after coming off security duty at the offices of the Chugoku Shimbun. After the bombing he went back to the burning city. His wife Yukie, now 94 and living in Tokyo, said, “After the atomic bomb was dropped, he dashed out of our house in Kogomori (Fuchu-cho) and walked around the city for days.”

On the afternoon of August 6 Mr. Osako found a bandaged Shuetsu Matsumura, then 45, at the ruins of the Chugoku District Military Headquarters, where he was chief of staff. Mr. Osako pulled information out of Mr. Matsumura. “A new type of bomb was dropped with a parachute,” he said. The prefectural government had set up temporary offices at the Higashi Police Station, where the police had been able to limit the fire damage. There, on August 7, Hirokuni Dazai, then 34 and head of the special political police section, gave Mr. Osako an announcement from the governor and asked him to give it to other papers as well. Mr. Osako recounted this episode in “Hiroshima 1945.”

A copy of the governor’s announcement, which was issued in the form of a printed handbill, is held in the prefectural archives. “We must believe in ultimate victory to the end,” it said. The announcement was carried in the August 11 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun, which was printed for the company at the western Japan offices of the Mainichi Shimbun. The war went on.

Despite a lack of paper and ink, on August 7 the reporters who had experienced the A-bombing formed the “kudentai” to convey information verbally.

Haruo Oshita, then 42 and page editor, wrote about the duty of reporters to “prevent the feelings of the people from being aroused” in an account included in “The End of History,” a description of the devastation of Hiroshima and a detailed account of the actions of reporters, which was included in “Hiroku Dai Toa Senshi” (Secret Records of the Greater East Asia War), a 12-volume history published in 1953.

Mr. Oshita himself told people about “the emergency relief plan for the victims, temporary facilities to house the sick and wounded, relief food supplies, the extent of the damage, etc.” “I walked about shouting, and adding that people shouldn’t worry.”

From their base at the temporary prefectural offices, the reporters went to Hijiyama (Minami Ward), Nigitsu (Higashi Ward) and the East and West Parade Grounds, which had become evacuation areas, and to residential areas that had escaped the fire.

“Many people who had been separated from their friends and family got news of them from the kudentai, and many of the seriously injured who had collapsed by the roadside were taken in at relief stations thanks to them,” Mr. Oshita wrote.

Reports after the end of the war

The kudentai was formed at the request of the military and was under its direction.

An order from the military stated that, “The term ‘atomic bomb’ must not be used. Those who use it in conversation will also be punished.” “At some point somebody somewhere created the word ‘pikadon,’” Mr. Oshita wrote. Use of that word, which combined expressions for the flash (“pika”) and boom (“don”), “was not prohibited.”

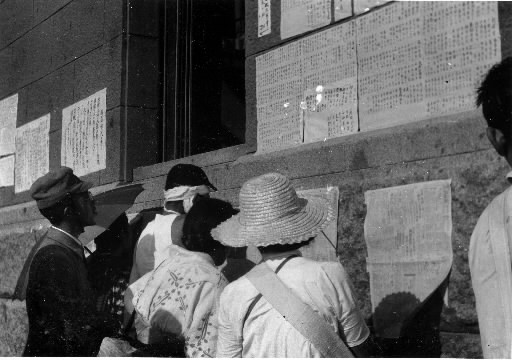

When editions of the Chugoku Shimbun that had been printed by other newspaper companies were delivered, they were taped to the walls of buildings that had survived the fires. On August 9, the Soviet Union entered the war against Japan and an atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

The August 12 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun carried a report from Hiroshima under the byline of a correspondent named Kishida. The headline said, “Duck with ‘high-performance tracer bombs’ too.” Who was this correspondent? Eijiro Kishida, then 30, worked in the Wire Service Department at the western Japan offices of the Asahi Shimbun. He arrived in Hiroshima from Kokura (now part of Kitakyushu) on August 7.

Mr. Kishida died at the age of 94 in Sakai, Osaka Prefecture, but he provided an account of the kudentai, which he had participated in, for the August 5, 1987 edition of the Asahi Shimbun. “News reports always closed with the expression ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. “But the members of the kudentai knew all too well that it was just an attempt to make people feel better.”

Mr. Kishida’s report on the devastation he saw in Hiroshima was printed one week after the end of the war in the August 22 edition of the Asahi Shimbun published by its western Japan offices. Beside a headline saying “Number of dead reaches 80,000” there was the byline of another correspondent named Yoshida, who was also reporting from Hiroshima.

“Were these bodies all around dead or alive? The faint groans of his pitiful countrymen were all this stumbling reporter could hear,” he wrote.

This reporter, who entered the hypocenter area on August 6 and wrote about what he saw, was Kunso Yoshida, then 38. He had left the Chugoku Shimbun in 1939 and gone to work at the western Japan offices of the Asahi Shimbun, according to the 1994 edition of the Asahi’s Who’s Who.

The Chugoku Shimbun tracked down his sister, Yachiyo Omoto, 86, who lives in Minami Ward in Hiroshima. “My brother had returned to his birthplace in Hatsukaichi after he was bombed out of Moji (now part of Kitakyushu). He came looking for me in Miyako-cho (Nishi Ward),” she recounted. After the war Mr. Yoshida served as a member of the town council in Hatsukaichi. He died at the age of 66.

The first photos of the ruins of Hiroshima to be published in the Chugoku Shimbun were carried in its August 23 edition. They were taken by Satsuo Nakata, then 25, of the Domei News Agency, who entered the city on August 10 along with an Osaka-based Navy survey team. He took the photos from the roof of the burned-out Chugoku Shimbun building. “There is a steady stream of civilian casualties,” he reported.

From the end of the war through the Allied Occupation, there was coverage of the cruelty of the atomic bombing and the devastation of Hiroshima. The Chugoku Shimbun hastened to resume publication of its paper without the assistance of other companies in Nukushina (now part of Higashi Ward) on the outskirts of the city.

(Originally published on April 14, 2012)

Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 5)